How 15 Million Inaccessible Acres of Public Lands in the West Impact Outdoor Recreation

“Fragmented ownership, increased outdoor recreation, and the lack of a federal policy addressing public lands have all ‘set the stage’ for public access problems.”

Public Land and Resources Law Review, 1982.

What Does Public Access Mean?

When outdoor and off-road enthusiasts talk about having access to places to recreate, if we talk about it at all, we’re usually referring to where our chosen form of recreation is allowed. This makes sense, as just about every route and area has restrictions on activities. For example, travel by foot and by horse is allowed in Wilderness areas, but travel by bike and motorized vehicles is not. On other public lands, some trails allow mountain bikes, in addition to horses and hikers, but restrict dirt bikes and other motorized vehicles. In yet others, there are routes with vehicle width restrictions, but certain motorized recreation is allowed.

But there’s another aspect of access to public land that impacts all forms of outdoor recreation: legal access. Due to a series of policies through time, some tracts of public land were isolated or enmeshed in a checkerboard pattern of land ownership. After analyzing our land ownership map data, we found there are more than 15 million acres of federal and state lands in 11 western states that are “landlocked,” or inaccessible because they are surrounded by private land. That means everyone, no matter their chosen outdoor pursuit, is locked out of these places unless they get permission from a neighboring private landowner.

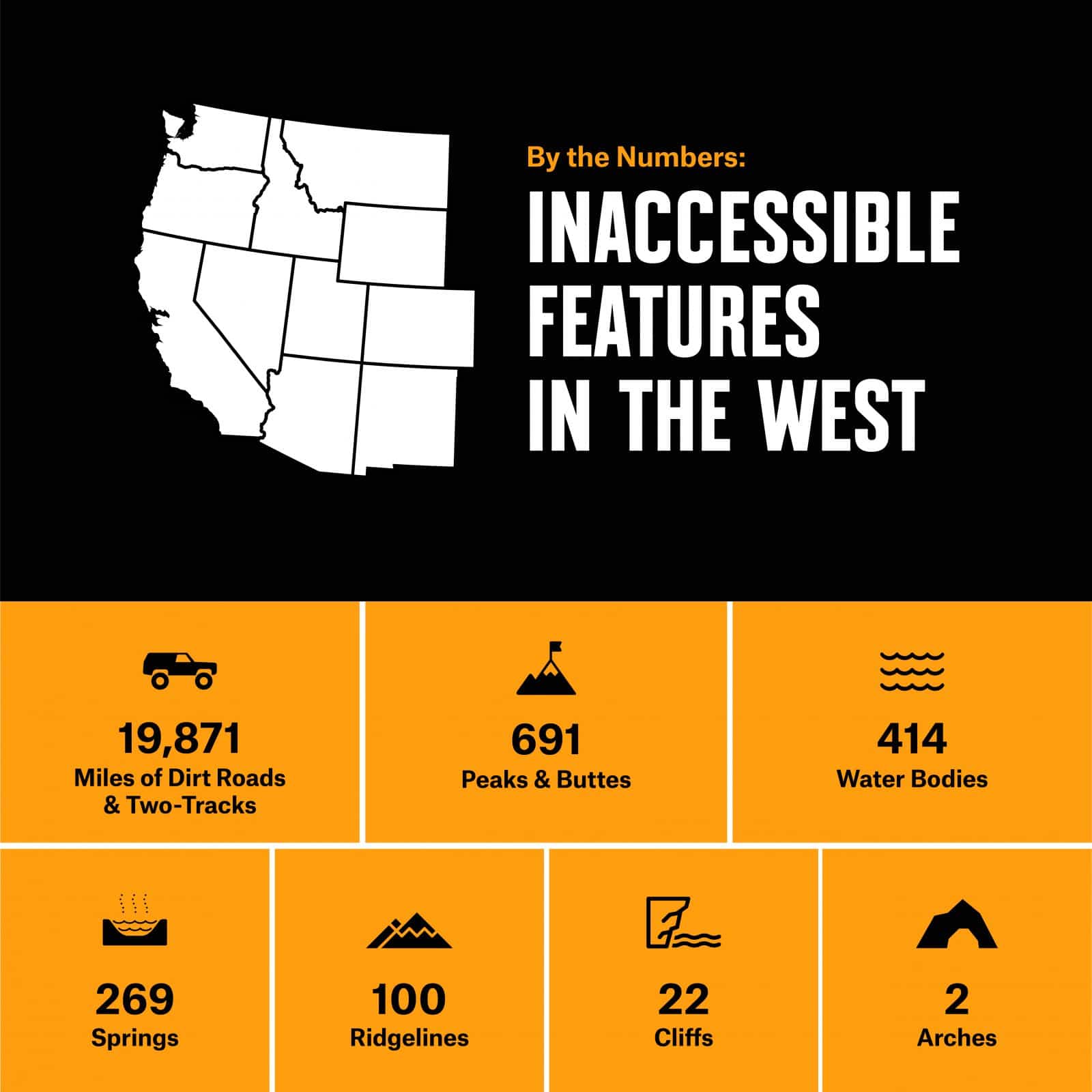

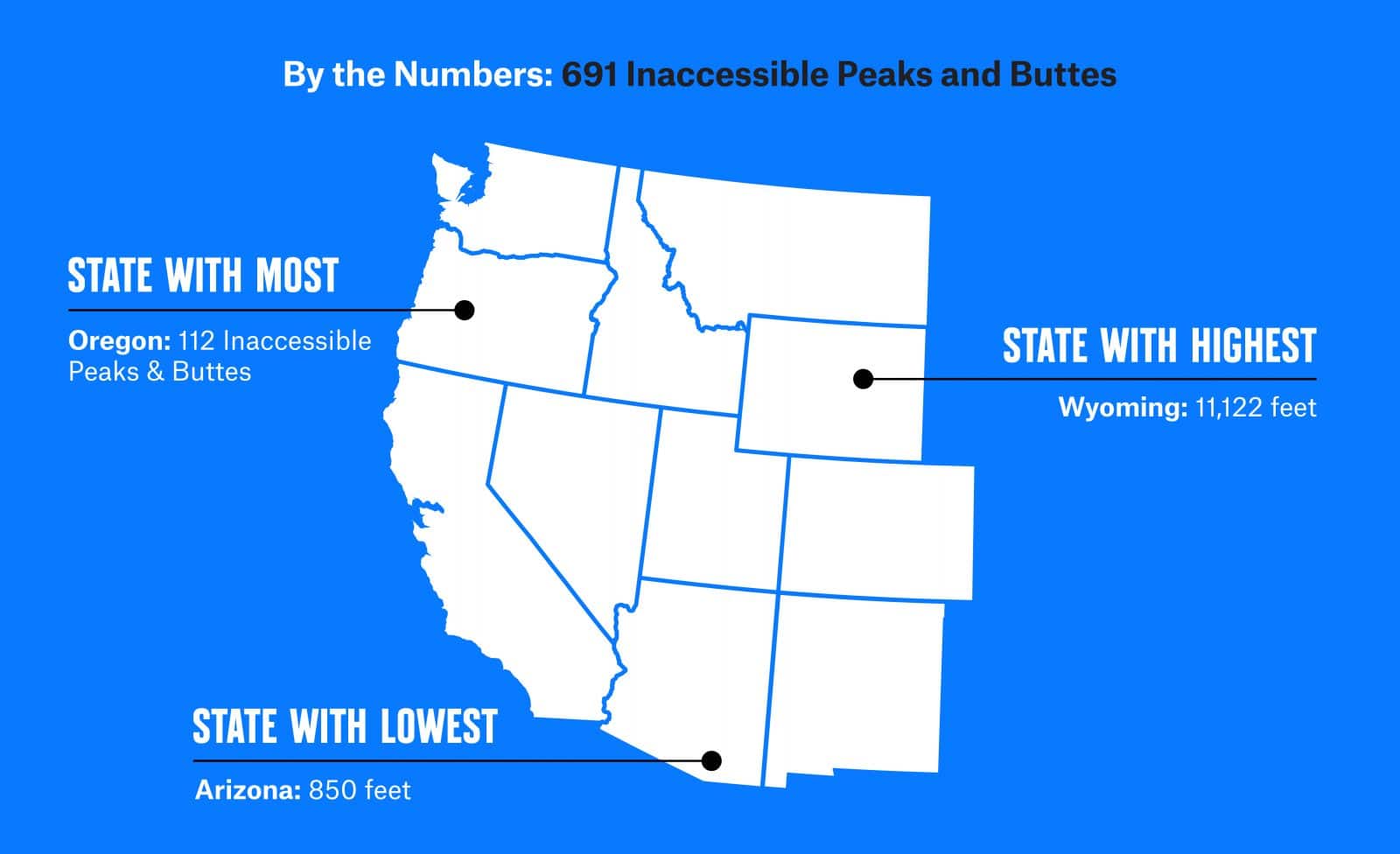

What’s on Landlocked Public Land in the West?

Roughly 80% of the 15 million landlocked acres we identified are located in the arid grasslands and deserts of Montana, Wyoming, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico. More than 1.5 million acres are located in the ecologically diverse landscapes of Washington, Oregon, and California. Another 1.4 million acres are located in the mountain and inter-mountain regions of Idaho, Utah, and Colorado. These inaccessible lands hold potential for peak-bagging, skiing, scrambling, climbing, camping, overlanding, and rock crawling—but we can’t get to them.

Isn’t It Better To Leave These Places Untouched?

Just because a parcel of public land cannot be legally accessed by the general public does not mean it is an untouched Eden of ecological purity. The neighboring landowners have access to landlocked parcels, sometimes without any oversight of the land management agency, since access for agency staff may not be guaranteed without an administrative easement. That’s right—the land management agencies, in some cases, can’t even legally access land they are charged with managing. Furthermore, having small fragments of public land scattered across the landscape does not guarantee safe passage for wildlife that require large territories or travel long distances.

What Do Landlocked Public Lands Mean for Recreation?

Outdoor recreation gear sales are surging, and visitation to our public lands break new records every year. Many outdoor enthusiasts feel like their “secret” open spaces have been discovered and are getting crowded beyond what academics refer to as experiential carrying capacity—that point where there’s too many people around to enjoy the experience of being in nature. The health benefits of time outdoors have been well documented, including benefits for anxiety, blood pressure, mental focus, and immune system function. But are we likely to receive those benefits if we have to battle for parking at the trailhead or spend many tense hours driving around in search of an open campsite? For the sake of public health, we need to have more nature to go to. Unlocking inaccessible lands can provide more options.

However, land is being developed at a breakneck pace. From 2001 to 2011, 2.75 million acres of natural area in the West were developed to expand towns and cities, increase energy infrastructure, and build more transportation. Many Westerners have a story about losing access to public land in their area. Oftentimes, it’s an anecdote about a large parcel being subdivided and a crop of new houses suddenly blocking an access route to public lands where a farmer or rancher used to informally allow it. Without any action to make those routes legally binding through an easement, more public land access will be lost.

How Can Land Be Unlocked?

Luckily, we are not condemned to simply accept the crowds and lament over the lost places we once explored. Inaccessible public lands can be unlocked, but it will require the strategic use of resources and the outdoor public coming together—and a lot of time. There is no single policy tool that will rewrite the patchwork history of land ownership in the West. But there are some bright spots.

Thanks to the passage of the two federal acts—the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act in 2019 and the Great American Outdoors Act last year—$27 million will be dedicated to improving access to difficult and impossible-to-access public land every year. This funding is part of the Land and Water Conservation Fund’s (LWCF) $900 million budget. Since 1965, LWCF money has been used to acquire recreational lands and waters, develop outdoor recreation facilities, protect the habitats of endangered species, and preserve forests. The Department of the Interior estimates that LWCF has already protected 2.37 million acres.

LWCF and other funding sources, coupled with a variety of legal tools, have helped land trusts, conservation organizations, and trail associations connect disjointed tracts of public land, improve water access, and secure public access easements across private land through agreements that benefit the landowner. Projects like these reconnect habitat patches for wildlife and secure recreational opportunities for communities.

The Dingell Act of 2019 also requires federal land management agencies to collect public input regarding places where access to public land should be improved. Specifically, the agencies are seeking input on difficult-to-access or impossible-to-access public land parcels that are at least 640 acres, or one “section” in the Public Land Survey System. While the agencies have already completed their first round of lists, the priorities must be re-evaluated and published every two years until 2029. Keep an eye out for future public comment periods with the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. If there’s an inaccessible or difficult-to-access parcel of public land that you’ve discovered, you can submit its location to the managing agency to let them know improving access to that area is important to you. If you’re unsure which agency manages the parcel of public land you have in mind, well, that’s what onX is for. Tap the location on your onX App, and the query card will tell you which agency manages it.

Money Speaks, and So Can You!

In 1982, the Public Land and Resources Law review stated, “…outdoor recreation is not on an equal footing with other public land uses because of its new popularity and its nonrecognition as a viable public land use.” But in 2018, the U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis included an assessment of the outdoor recreation industry for the first time. The results indicated that outdoor recreation contributed $412 billion to the economy and supported 4.6 million jobs. Outdoor recreation is no longer on the sidelines of public land use decisions. The combined economic force of our pursuits means we have a voice, and when hunters, anglers, backpackers, skiers, mountain bikers, and off-road riders are aligned, our voices carry that much further.

Think about the access challenges in your area, and spend some time panning around your onX App. Are there inaccessible or difficult-to-access recreation possibilities on public land that you’d love to explore? Let the land management agency know what that means to you. While you’re at it, let your state and federal representatives know why public access to outdoor recreation is important to you. Then, consider donating time or money to your local land trust or trail organization. Individually, our actions may feel small, but if everyone participates locally, the impacts will be felt nationally. We’re all in this together.