A Hopeful Idea for Earth Day: Let’s Protect 30% of Land and Water by 2030

Today is Earth Day, an event to celebrate the power of people joining together on behalf of our planet, to raise awareness about environmental issues, and to increase support for solutions. The world’s first Earth Day, 51 years ago, was largely a response to industrial pollution. Over the following two decades, a series of laws were passed to safeguard human health. Since then, new environmental concerns have come to the fore, most notably climate change and the loss of species and habitats. In the United States, we lose a football field’s worth of natural areas to development every 30 seconds, according to Conservation Science Partners. That represents a lot of lost opportunities to hike, run, ride, and enjoy the outdoors. Habitat loss also spells trouble for the species that used to live in all that open space; roughly 1,800 species in the U.S. are at risk of extinction. And while these issues seem daunting to say the least, one proposal to both combat climate change and protect biodiversity is gaining momentum. And it looks promising for outdoor recreation, too.

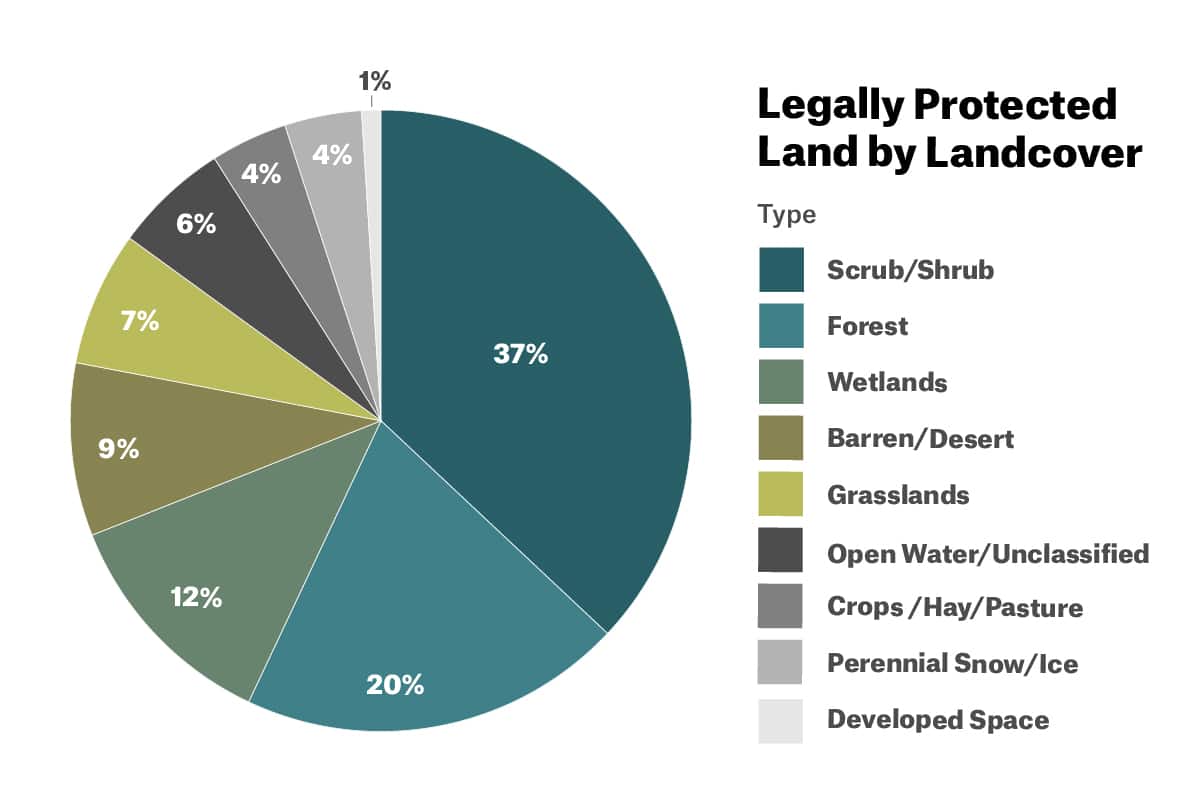

The plan that would be beneficial for the climate, biodiversity, and outdoor recreation is to protect 30% of the world’s land and water by 2030. First proposed by the world’s leading ecologists, the idea is known as 30×30 (sometimes written Thirty by Thirty or 30 by 30). The concept stems from the fact that when ecosystems are disrupted, the services that nature provides to us for free—pollination, removal of toxins, soil formation, nutrient cycling, and flood mitigation to name a few—are at risk of toppling like a house of cards. That’s bad for humanity and wild species. Properly functioning ecosystems also hold on to carbon: plants suck carbon dioxide out of the air through photosynthesis, and some of that carbon ends up stored in soil. Healthy plants and soils currently store 11% of the greenhouse gases that are released in the U.S. in one year, but scientists think that number could nearly double if we protect and restore more land.

Now, federal agencies and 70 mayors in the U.S., as well as leaders in 50 other countries, are working on plans to protect or conserve 30% of the lands and waters within their boundaries. So what exactly does it mean to protect or conserve? And how much land in the U.S. already qualifies? Let’s dig in.

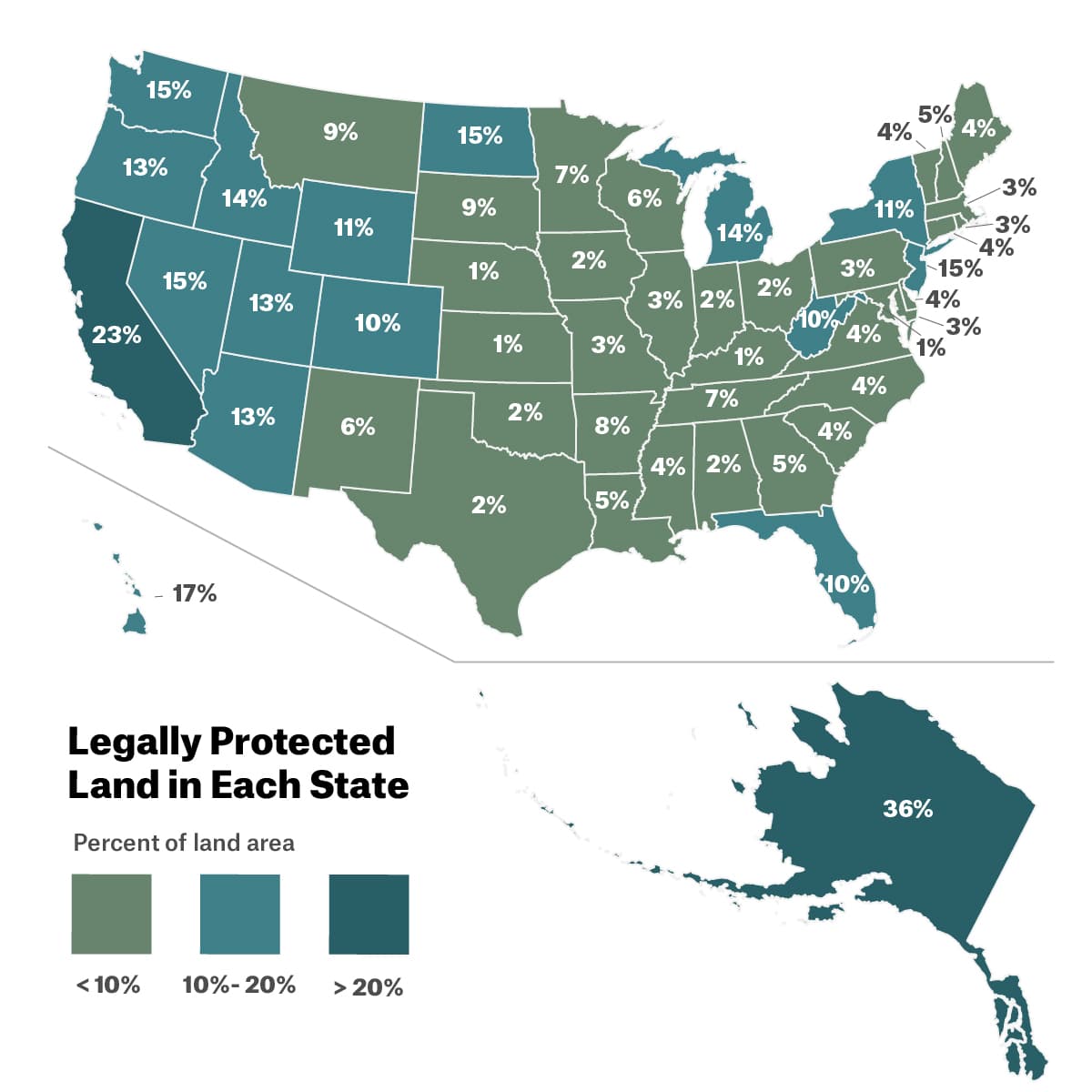

The Starting Point: 12% Protected

According to data and definitions compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey, the amount of land in the U.S. currently protected is around 12% of the country’s land base. These places have legally enforceable protections, where natural and ecological functions are allowed to proceed with minimal levels of human interference. Any land management in these areas must mimic natural processes.

Using this definition, some of the protected land designations are:

- National and State Wilderness

- Wilderness Study Areas

- National and State Parks

- National Conservation Areas

- Wild and Scenic Rivers

- Wildlife Refuges

- Private Conservation Easements

These designations tend to be the dramatic landscapes that people from other continents travel to North America to see, even though many are not easily accessible for all Americans. Every state in the country has some type of legally protected land, but the majority is concentrated in western and northern states, so some ecosystems have large areas that are protected, while others are barely represented in the 12%. In fact, according to one study, many high-value areas for biodiversity and ecosystem carbon storage are in the relatively unprotected Southeast.

While one-third of legally protected land allows recreation of all types, the remaining two-thirds are either privately owned or highly regulated. For example, private landowners can secure enduring protection of their land with a conservation easement, but they are not obligated to open their land to the public. Federal Wilderness areas, the designation that describes the highest level of protection in the U.S., are not open to bicycles or motorized recreational vehicles, although horses and hikers are allowed. Parks and wildlife refuges have their own regulations, too.

However, legally protected areas can still be threatened by development—as the history of mining in and around the Grand Canyon, oil lease sales in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and shrinkage of Bears Ears National Monument demonstrate. Designations can change and lines on a map can be redrawn.

Therefore, the first step toward protecting enough land by 2030 is not losing any land that’s already protected. In 2017, 3.3 million acres lost their protected status. The outdoor community and Tribal governments have been critical in the fight to restore those designations, but these are ongoing battlegrounds. We should all keep a watchful eye on our favorite places, and call or write to our representatives when development proposals threaten those places.

Assuming we don’t lose ground and the 12% of protected land retains their designations, the remaining 18% of additional land that would need to be protected within the next 10 years to reach the 30×30 goal would be over 650,000 square miles. That’s nearly the size of Alaska or, to put it another way, the size of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Montana combined.

So where do we find the remaining 18%? We need to look elsewhere—to other types of public land, private land, and to our own backyards.

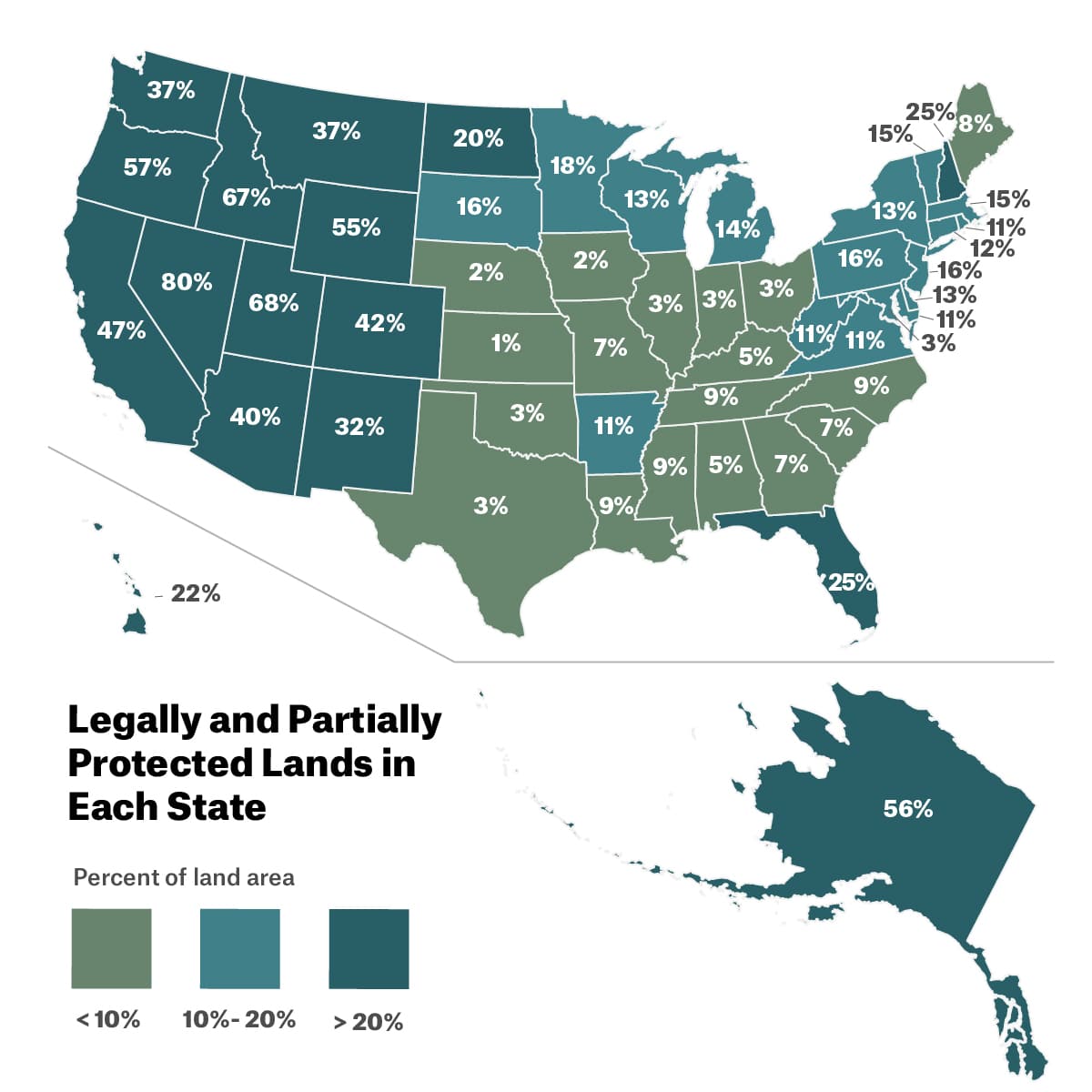

Closing the Gap: Partially Protected Public Lands

When you head out for a day of riding, skiing, or hiking on public land, chances are you’re going to a place that’s managed under an official plan, but is not necessarily permanently or legally protected. Let’s refer to these as “partially protected.” According to the Protected Areas Database, these places are protected from “conversion of natural land cover for most of the area” (think: they can’t be paved over or turned into condominiums). They give protection to federally listed endangered and threatened species, and may support biodiversity and effectively store carbon.

This broad category includes areas such as:

- Watershed Protection Areas

- Natural Resource Areas managed by state and local governments

- Forest Stewardship Agreements

- Private Ranch Easements

Additionally, federally managed lands in this group—if not designated under another protected status—include:

- National Forests

- National Grasslands

- National Seashores and Lakeshores

- National Recreation Areas

- Inventoried Roadless Areas

- Bureau of Land Management Land

By adding all the acres of partially protected land to the total area of legally protected land, the total jumps from 12% to 30% of the land base of the U.S. Does that mean we’ve already achieved the 30×30 goal? Not so fast.

Right now, many public lands that fall into this partially protected category are currently providing land for agriculture, timber, energy production, and mineral extraction. While these activities release carbon and disrupt ecosystems when not done sustainably, we can’t immediately put a halt to them everywhere. Nor can we quickly give all partially protected lands fully protected, federal designations. The latter has historically taken decades to pass in Congress.

So what can be done to ensure more partially protected landscapes trap carbon and support biodiversity to help reach the 30×30 goal? The answer may lie in the way land is managed, rather than on official labels and designations. We need to reassess what we really need from our public lands.

| 30×30 Opportunity Areas | Amount of Land (Acres) | Percent of U.S. land area |

| Bureau of Land Management* | 210 million | 9% |

| United States Forest Service* | 138 million | 5.9% |

| Inventoried Roadless Areas | 58 million | 2.5% |

| National Recreation Areas* | 4.7 million | 0.2% |

| State and Local Resource Management Areas | 40 million | 1.7% |

Each unit of our federal lands is managed by a plan that governs land uses, natural resources, and activities. However, many of these plans are overdue for a revision. Through the planning process, we get to have a say. If the goals of 30×30 get prioritized when plans are being revised, more of our public lands can provide space for carbon storage and biodiversity for decades to come, even without any official designated status. You can see what’s open for comments on BLM lands and USFS lands right now.

Another bright spot is the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), which uses royalties from offshore oil and gas leasing to fund conservation and recreation. Since the fund was established in 1964, 8 million acres have been purchased to create new parks and public lands. In 2019, LWCF was permanently reauthorized by Congress so it won’t expire again. Then in 2020, the Great American Outdoors Act guaranteed that the funds cannot be siphoned off for other government spending.

Considering Other Protected Areas

Increasing land protection does not have to happen exclusively on public land. Sixty percent of the land in the U.S. is privately owned, but less than 1% of private land is legally protected in agreements known as conservation easements. Many of our nation’s most bio-diverse and least-protected areas are on private land. The Land Trust Alliance, through 1,000 land trusts around the country, has committed to working with private landowners to conserve another 60 million acres by the end of the decade via land acquisitions and conservation easements. If that target is met, it would mean another 2.5% of land is protected.

Finally, there’s a type of land ownership within America’s borders that has not been tallied thus far for the 30×30 goal. The vast majority of Native American lands are not considered protected according to the classification system of the Protected Areas Database. But globally, Indigenous peoples’ territories make up 22% of the Earth’s surface and host 80% of the planet’s biodiversity. In the U.S., natural areas in Tribal lands have been lost at a much slower rate than federal, state, or other private lands. So it’s safe to say this is a limitation of definitions and data, rather than an absence of protected areas within Native lands. Going forward, the Department of the Interior, which houses the Bureau of Indian Affairs, will “undertake a process of broad engagement” with every level of government including sovereign Tribal nations, a process that may identify both land management strategies and acreage to bring us closer to the 30% goal.

Looking Locally

One way to ensure that all communities have functioning ecosystems, wildlife habitat, and access to the outdoors is through a variety of conservation and public access easements. There are numerous grants and tax incentives available to landowners who conserve and protect habitat on their property. Some conservation agreements provide for public recreational access, while some keep agricultural and timber lands working. Some do both. No matter the details, landowners get a financial benefit and communities get the benefit of a protected watershed, airshed, or viewshed. Interested landowners can find land trusts in their area using this map. In addition, numerous state programs provide incentives to landowners to enroll their land in programs that benefit both habitat and public access. If you don’t own acreage but want to help conserve land in your area, consider volunteering your time or donating to a land trust in your area.

Basically, everyone can help the country reach this goal. If you live near public lands, seek out groups in your area that work with land managers. Participate in a public comment period when there is a proposal for the parks and public lands you care about. Call or email your local, state, and federal representatives. You can also check out national organizations that advocate for your outdoor interests, whether you’re into human powered recreation, hunting and fishing, or motorized recreation.

We may think of large tracts of land when we think about protected landscapes, but even small parcels in urban and suburban areas can provide habitat for small wildlife, especially pollinators, and help trap carbon. In 16 years, 13.8 million acres of natural area were lost to urban and suburban sprawl. Not only does that mean the people living in densely populated areas have fewer opportunities to get outside and enjoy nature, it also exacerbates the impacts of natural disasters like flooding and wildfire. Carefully managed areas that provide outdoor recreation most of the year can serve as buffers during emergencies. Planning our cities for higher density mixed with dedicated green spaces featuring plenty of native plants will keep the air cleaner and give more people access to the outdoors. The Trust for Public Lands wants to ensure everyone has a park within a 10-minute walk from home. Check out your city’s park ranking, find parks near you, and learn how you can get involved.

Want to make an even more direct impact? Look up the size of the park closest to you, or add up the areas of all the parks in your city using onX Backcountry. Calculate 30% of that area. Then get a group of your friends and neighbors together and write to your local parks department—or better yet, attend a public planning meeting—and ask that they replace 30% of their lawns with native plants. It might even be cheaper than all the care that lawns require.

If you own land, even a small sliver of land in a city, you can conduct the same 30% exercise on your property. Think about the total acres or square feet you steward. Then research the plants that are native to your area. Which grasses, flowers, shrubs, and trees could you reintroduce to your habitat? It may feel like a small and insignificant step, but native plants can support pollinators like insects and birds. If you own farmland, you might even be able to enroll your pivot corners in a program to provide habitat for upland birds.

On April 27, the Department of the Interior will submit a report to the National Climate Task Force, which will outline principles to pursue the 30×30 goal. This report will be informed by stakeholder input from Tribal leaders, agricultural producers, foresters, hunters and anglers, and outdoor recreation advocates.

So while Earth Day is not typically a day for breaking out the bubbly, the hope offered by 30×30 is at least worth cracking open a carbon-neutral cold one. Cheers to Earth!