Did the 10th Circuit Court Just Make Corner Crossing Legal? It’s Complicated.

Court ruling favoring Wyoming hunters clarifies access for more than 3 million acres of public land, but there are some important considerations.

A decision last week by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals is being widely celebrated as a long-awaited victory for public land access. The case focused on four hunters who used an A-frame-shaped ladder to step from one section of federal land to another in Wyoming, passing over a property corner shared with two parcels of private land. The North Carolina-based owner of the private land sections sued the hunters for $9 million in damages in the form of diminished property value.

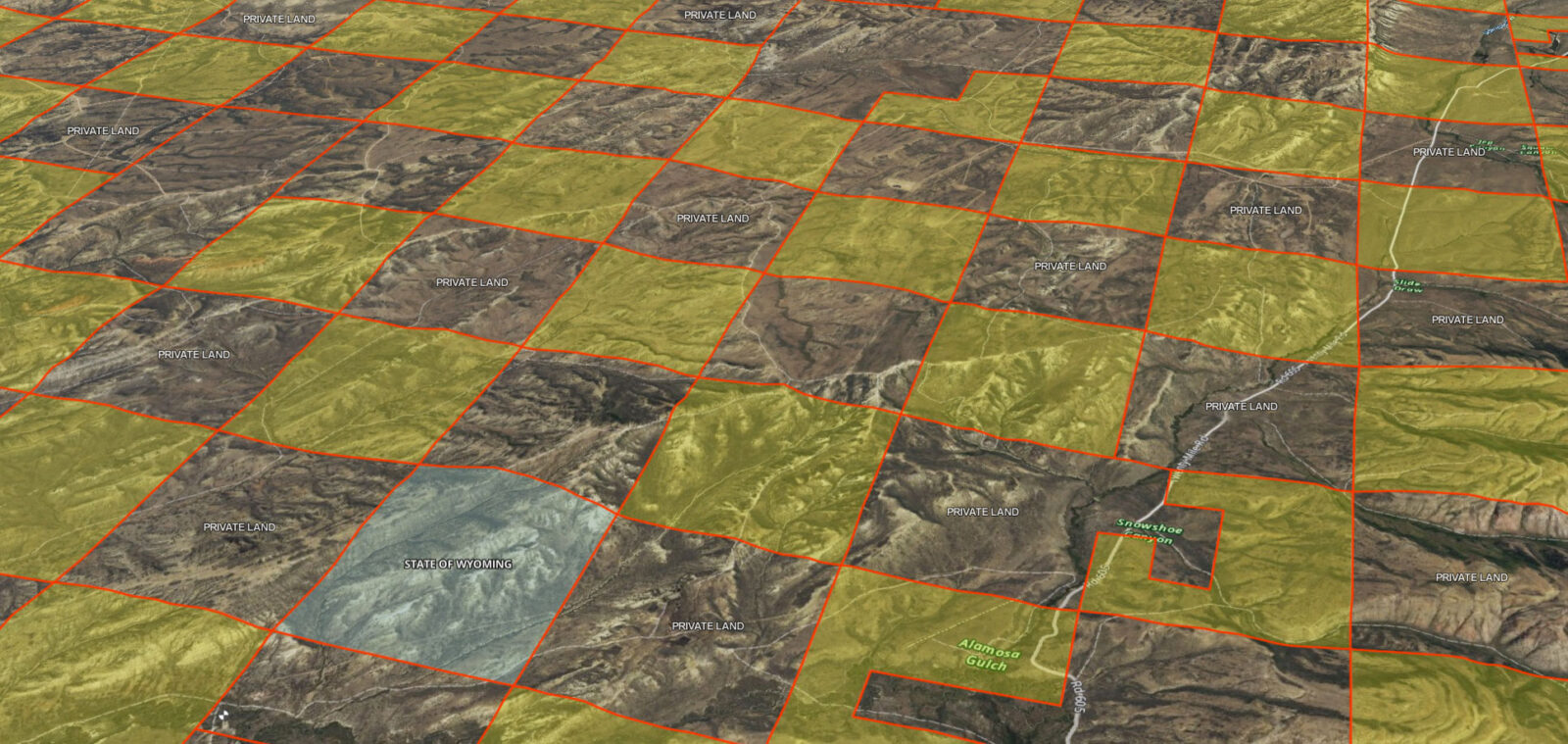

The hunters had “corner crossed.” Up until last week, the act of corner crossing existed in a legal grey area that decades of litigation and failed bills had yet to clarify. Western hunters tended to avoid the practice, wary of its repercussions, but were familiar with the conundrum: vast acres of public land that exist just out of reach, a mere step away. The origin of this dilemma is the way the West was allocated in the mid-1800s, in a checkerboard pattern of ownership where private and public land parcels alternate.

To make their decision, the 10th Circuit judges relied on case law stretching back decades and the 1885 Unlawful Inclosures Act (UIA), which was originally passed to pacify the “range wars” between cattle barons 150 years ago. The three-judge panel ruled unanimously that the landowner could not deny access to federal public lands for lawful purposes. They upheld a lower court’s decision “that the Hunters could corner-cross as long as they did not physically touch” the private land.

“To ‘prevent the absorption and ownership of vast tracts of our public domain’ by the cattle barons… Congress passed the Unlawful Inclosures Act of 1885. In essence, the UIA was designed to harmonize public access to the public domain with adjacent private landholdings.”

—Iron Bar Holdings, LLC v. Cape, et.al. (2025)

Landlocked: Public land which is surrounded by private land, without any public roads or adjoining public lands providing access.

Corner-locked: A sub-type of landlocked public land, in which a public land parcel only touches other public land at one or more corners.

What does the court’s decision mean for hunters and other outdoor recreationists in the West? Before setting out, it’s important to note how the law works, nuances of the ruling, and that corner crossing still presents physical and technological challenges.

10th Circuit Jurisdiction Only

The 10th Circuit Court’s ruling last week directly applies only to the area within that court’s jurisdiction, which includes Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Wyoming happens to lead the nation in “corner-locked” public land with 2.4 million acres. Outside of this six-state jurisdiction, corner crossing remains a legal gray area: a court in another circuit might reference this ruling as precedent, but any proceedings would start back at “zero” with a new case.

Case Law Sets Precedent, Not Absolute Protection

“Law” is a broad term that incorporates constitutional law, statutes enacted by the legislative branch of government, and rules and regulations created by executive agencies (for example, the Department of Interior or state wildlife agencies). These examples of law apply broadly, in the abstract. But the term “law” also includes “case law,” which is specifically based on judicial decisions regarding concrete facts of a particular case.

The 10th Circuit’s ruling last week reinforced precedent in case law and confirmed the UIA–which prohibits the enclosure or assertion of right to public lands without title– “remains good federal law.”

Local law enforcement in the six 10th Circuit states could technically still charge someone for trespassing under a local or state law, but this ruling or other federal law could directly conflict. As such, the federal law would nullify the lower regulations. Unfortunately, that would only happen when the case got to court, instead of in the field. (Keep in mind: This is not legal advice).

In the Wyoming case, the landowner erected a barrier which the judges determined violated the UIA, but it also forced the hunters to devise a way to go up and over the corner, ensuring they never touched the private land on either side. That became an important detail in this case, along with the amended language of the Wyoming statute, which requires physical contact with the surface of private property for a violation to occur. A future case has the potential to have a different outcome. The specifics of each case will matter, unless a statute or regulation is enacted broadly.

Perhaps Not All Corners Can Be Crossed

There might not be a metaphorical “green light” at every corner between public land within the 10th Circuit. Notably, the court “interpreted the UIA to allow corner-crossing if access to public lands is otherwise restricted.” In other words, this ruling indicates that if there’s another public route into a parcel of public land, the corner may not offer a short cut or alternative access point. Corner-crossing into a parcel of already-accessible public land is not clarified by this case.

Ethical and Exact Corner Crossing

This new legal landscape may be fuzzy around the edges, but recommended best practices don’t veer far from general best practices in the outdoors. Use good judgement, be respectful of both land managers and private landowners, and when in doubt—and we acknowledge this evolving situation does indeed introduce some doubt—it’s better to lead with curiosity and ask questions. Gaining landowner permission is still the easiest way to ensure legal access. Otherwise, some key considerations include:

- It’s always important to be good stewards and neighbors, no matter where you’re hunting. By definition, corner-locked public lands border private holdings, so be considerate of all stakeholders.

- Deploy situational awareness, whether it’s topographical or interpersonal. If a situation arises that puts personal safety or security in jeopardy, call it a day and file a report if appropriate.

- Research the local and state laws regarding trespassing and public land access in the areas you plan to venture into.

- Be respectful of property, including and perhaps especially fences. Fences inhabit a particularly gray area in this new environment. Not only might a fence not accurately denote a property boundary, touching or using a fence to corner cross—even with complete precision—may still violate local or state trespassing laws. Plus, it’s best not to touch other people’s stuff.

- Corner crossing is a game of inches based on this ruling, and it’s possible a slight misstep could constitute an untested maneuver. That means you should have absolute certainty about the location of the legal corner. Some things to consider as you make that assessment:

- In order to corner cross with the exactness suggested in the ruling, find a survey-grade marker, usually referred to as a “pin” or “monument.”

- Corner pins can be notoriously difficult to locate thanks to vegetation, soil, or simply having been lost to time. They are not present at every corner so you cannot bank on finding one.

- GPS is not accurate enough to determine the exact intersection point of property lines. The GPS hardware in your phone or other handheld device is generally accurate to only 16 feet, and environmental factors such as canyon walls, thick tree cover, or buildings can reduce that accuracy. Read our blog about this topic.

- When in doubt, contact your local land manager or game warden to learn more about the details of the parcel you’re seeking access to and help ensure you stay on the right side of the law.

What Happens Next?

With over 3 million acres suddenly becoming at least not-illegal to access, the upcoming big game seasons across the West, the time of greatest interest in these remote parcels of land, will be a test environment for the reality in the wake of the 10th Circuit Court’s decision. Stay tuned to onX Hunt for more on this change and insights into the significant opportunities—and potential risks—for western hunters navigating this new landscape.

The information provided here does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice, and may not constitute the most up-to-date information. Links to third-party websites are intended for the convenience of the reader and do not endorse third-party information.