An onX Hunt Report

Overview

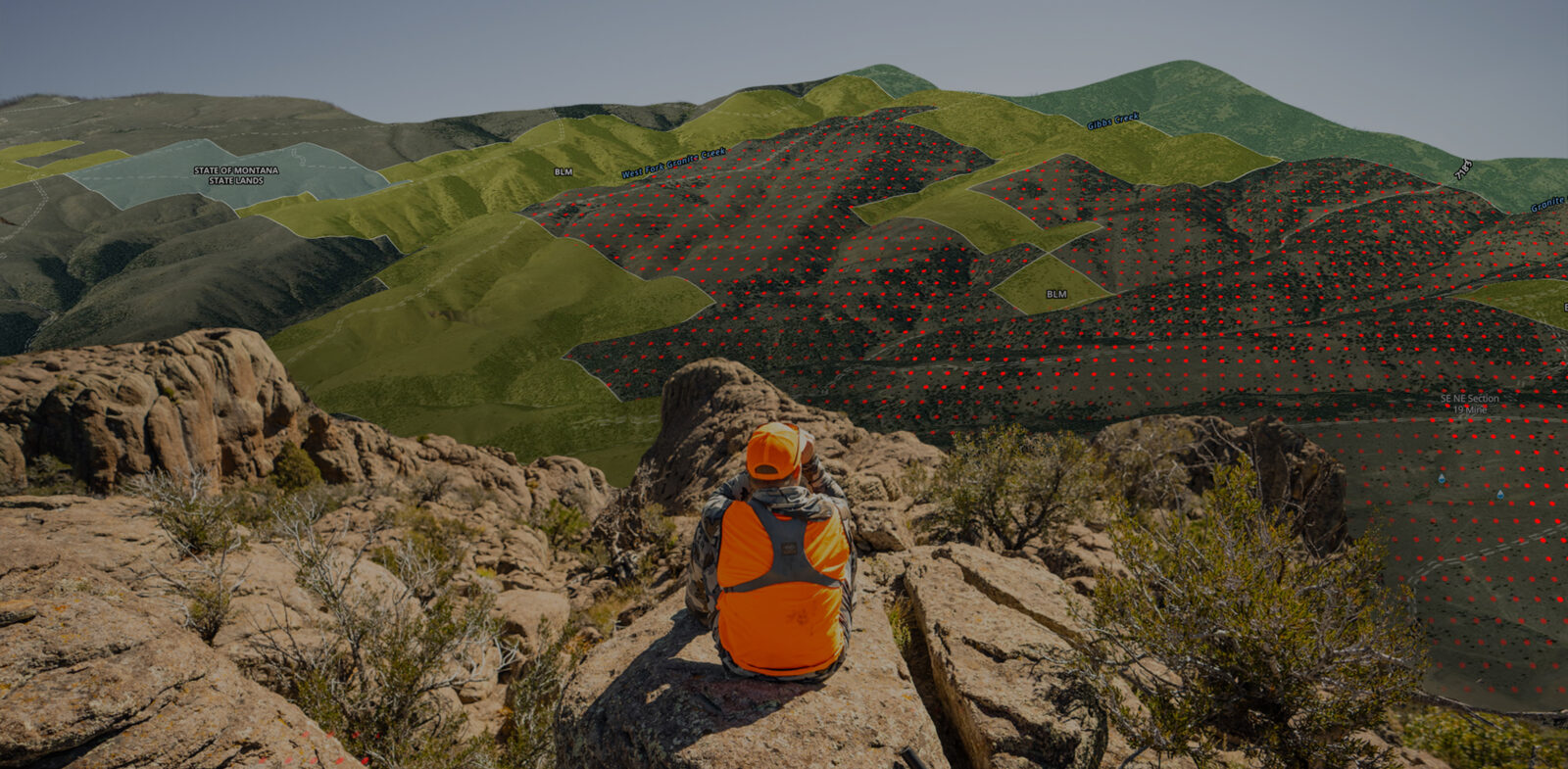

Every hunter knows the rush of a roadside glimpse of a perfect-looking draw or a ridgeline view of a copse of trees sure to hold game—and the letdown of seeing the fence. Private property. But behind thousands of those fences are millions of acres of private land that open to hunters each year through state and tribal programs known by a range of names and acronyms, but all providing a system of public access to private land.

These programs connect private owners and hunters in an arrangement that effectively “rents” access for the public at a cost of pennies on the dollar to American taxpayers and leverages more direct hunter support to provide a mutually beneficial system.

onX analyzed detailed map data across 27 states, surveyed more than a dozen land managers across the country, and interviewed landowners—what we discovered is a wealth of access opportunities unlocked by these unique and fragile programs.

- We found more than 30 million acres of private land are publicly accessible across 27 states—totalling the size of Pennsylvania.

- Landowners’ appreciation for hunting, public access, and habitat are core to the success of these programs, but lease fees from the states as well as benefits like liability coverage and regulation enforcement help make the success of these programs possible.

- The programs are threatened by hunter misbehavior and funding uncertainty. Hunters respecting landowners and taking extra consideration on these private lands is critical to keeping landowners enrolled and maintaining this access into the future.

- These acres also provide critical wildlife habitat and landscape-level conservation at an extreme value to the American taxpayer compared to the lengthy and expensive process to buy land or negotiate easements.

Whether used actively as hunting ground or passively as undeveloped wildlife habitat, these 30 million acres are unique in hunting and conservation spaces in that they’re not permanent designations. These access opportunities are reliant on agencies maintaining funding and staffing to support the programs and on landowners maintaining a willingness to open their gates for public access. This delicate balance requires care and intention to maintain—and 30 million acres are the price for getting it wrong.

Information within this document may not constitute the most up-to-date information and is not intended as advice. Opinions and links to third parties are informational and do not endorse third-party information.

Welcoming the Public, Passing on a Tradition

When Tom Billington looks out over his fields just south of Twin Falls, Idaho, he sees the history of his family, from his own grandfather who started out on a piece of the property back in 1906, through raising kids of his own, to his two adult sons who now run some of the land themselves. But he also sees the history of dozens—perhaps hundreds—of other families too. Fathers and daughters, mothers and sons from as far away as Colorado and New York City who have chased pheasants and waterfowl across he and his wife Jeannie’s 400-plus acres.

“I’m an adamant supporter,” Billington near-shouts into the phone, unable to restrain his passion. “I’m adamant about nature and I believe in youth getting to go hunting.”

The Billingtons open their farms each year through Idaho’s Access Yes! voluntary access program, which, like similar programs around the country, give hunters access to private property via enrolled landowners. The Billingtons have participated in the Idaho version for some 20 years, and while enrolled property owners are compensated with a modest stipend based on a number of factors such as type of land enrolled, habitat quality, and acreage, the money isn’t what drives the Billingtons.

“You have a little boy from New York holding a rooster in the rain, holding it like it was the greatest thing in the world,” Billington says. “It is phenomenal, that look in their eye.”

What are Voluntary Public Access Programs?

Commonly called “walk-in” programs in the Mountain West, voluntary public access programs are known by a range of names and acronyms that can confuse their common effort: to incentivize private landowners to open their properties to the public for hunting, provide critical wildlife habitat, and bolster ecosystem conservation efforts.

Administered at the state or tribal government level, there is no single entity overseeing these programs, though most draw at least a portion of their funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture via the Voluntary Public Access and Habitat Incentive Program (VPA-HIP). This funding—$50 million over the last five years, potentially triple that going forward—is up for reauthorization by Congress in the Farm Bill in 2023 and is critical to maintaining the health and continuity of these programs. Without it, the gates could slam shut on hunters’ ability to “walk-in” to an area equivalent to the size of Pennsylvania.

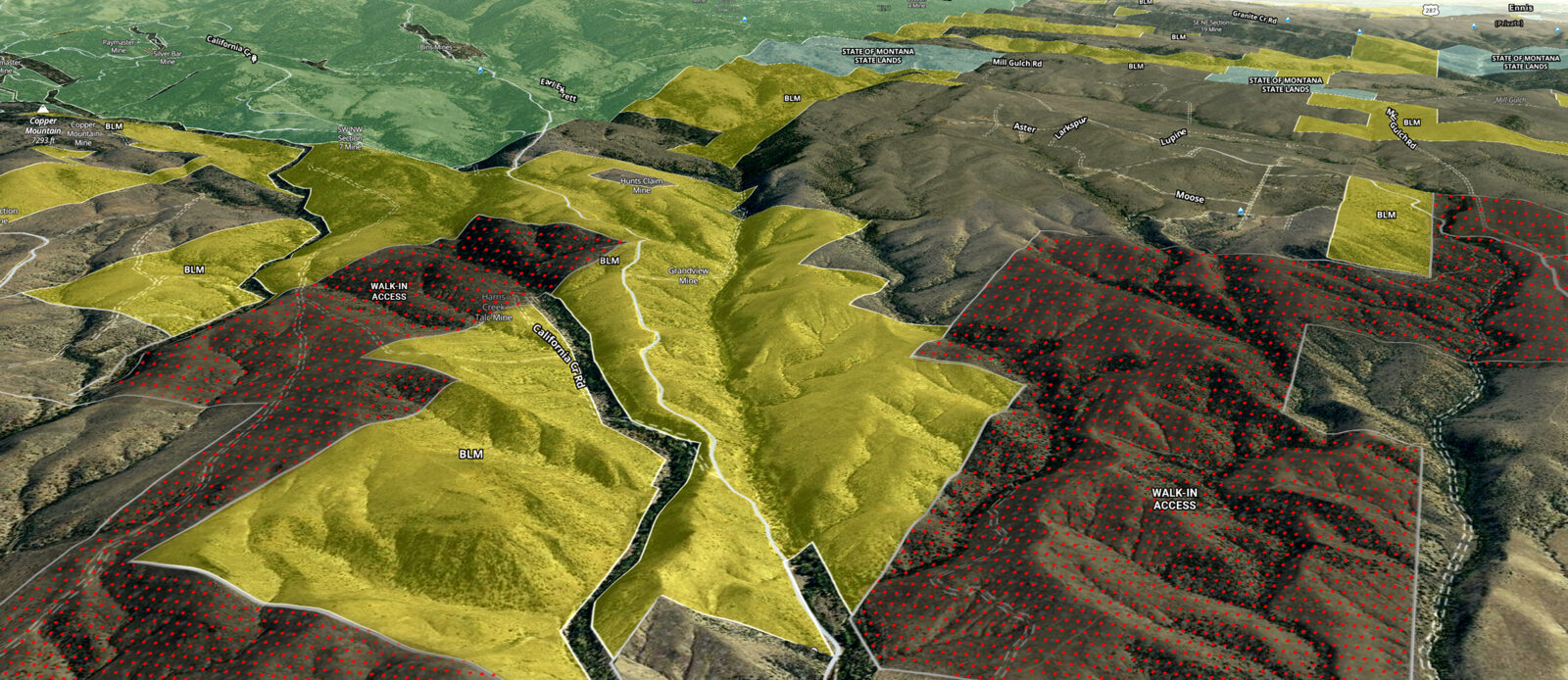

30 Million Private Acres Made Accessible

Though public land looms large in the minds of hunters, especially those chasing big game in the West, the reality is that 60 percent of land in the U.S. is privately owned. And while personal relationships and even letter writing can open up parcels on a one-to-one scale, there are tens of millions of acres of private land around the country available for hunters each year.

In this report, onX looked at programs which met the following criteria:

- They are administered by a state or tribal government agency, such as a fish and game or natural resources department.

- GIS mapping data for enrolled properties was available.

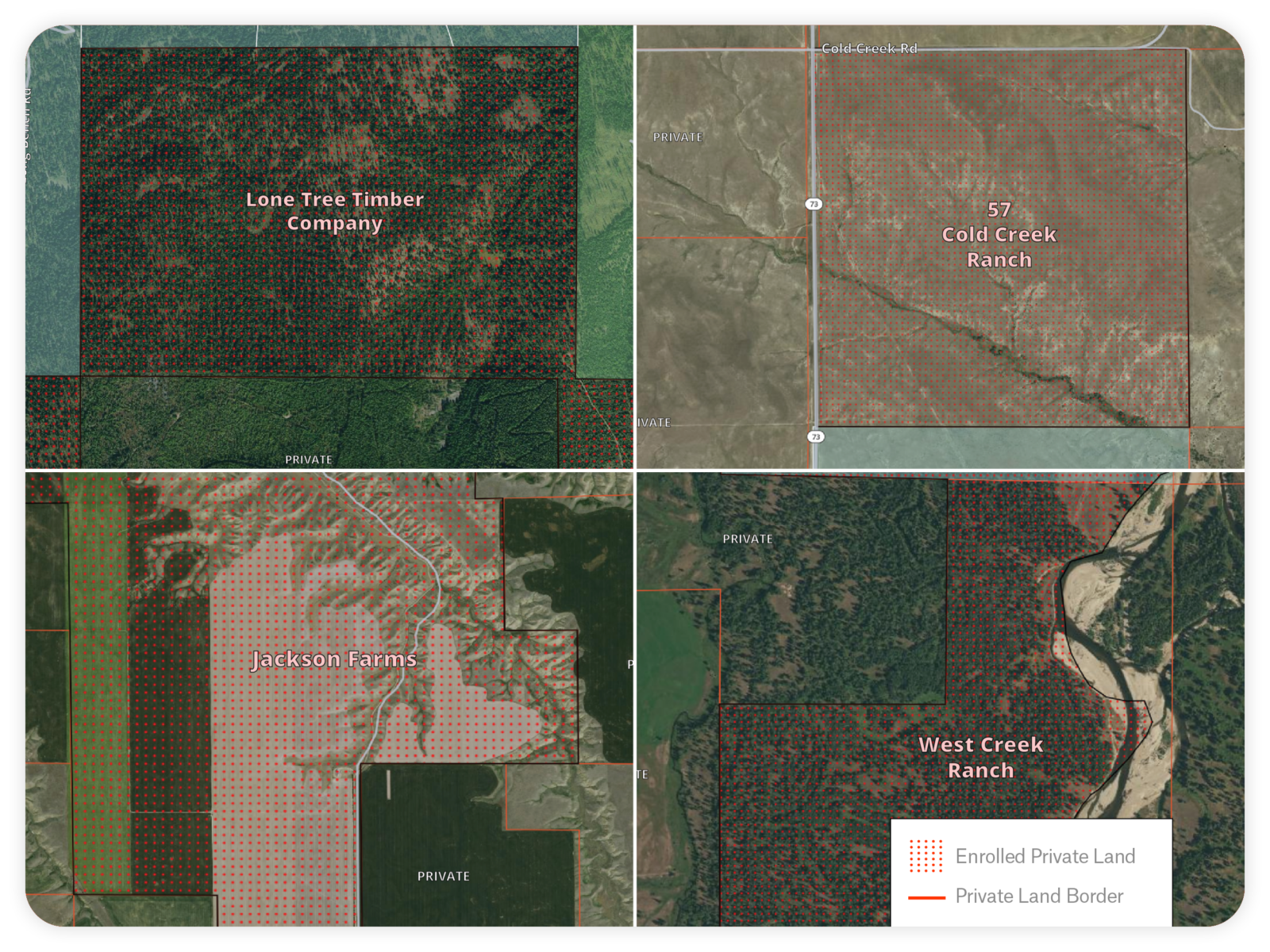

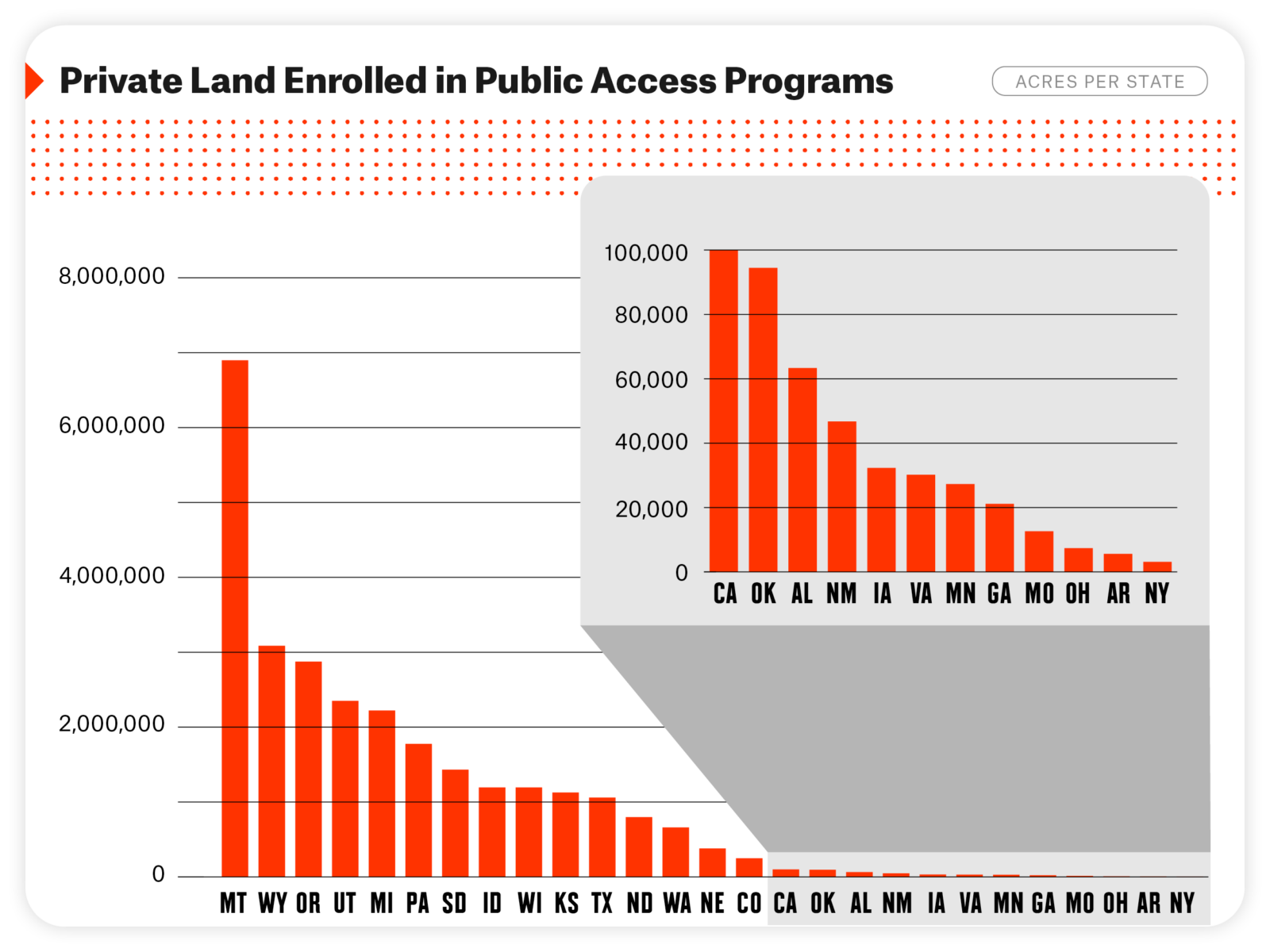

We found that across 27 states, there are more than 30 million acres of private land open to the public for hunting.

Known by a range of acronyms and names from Access Yes! in Idaho to WRICE in Arkansas, Block Management in Montana, “Walk-In Hunting Access” or WIHA in Kansas, and PALS in Virginia, some of these voluntary public access programs are also specifically tailored to the habitat and hunting for particular species, such as the Turkey Hunter Access Program in Wisconsin and the Upland Game Bird Enhancement Program in Montana.

Details regarding opening and closing dates, the rules and procedures of access, firearms permitted, and species that can be pursued vary greatly not only from state to state, but also from one property to the next. Furthermore, some states only have a single private land access program, while others have up to five different programs, each with unique opportunities for hunters, but also varied rules and regulations. This means private landowners, whether a single individual or a large corporation, retain more of a say in how their property is managed. But it also means more intense planning and research for hunters. For those willing to do their homework, it can mean thousands—even millions—of additional acres available to hunt in their state. And a separate study conducted by onX in 2021 found that only 8 percent of hunters take advantage of voluntary public access program land.

If your state isn’t represented in this report, it doesn’t mean there’s no such program. For example, certain states have private land access programs run by non-profit organizations, such as the South Carolina Wildlife Partnership, rather than a state agency. In addition, a handful of states decline to provide their private land access data to commercial businesses like onX, and we therefore were unable to incorporate those programs into our data analysis. Do your research and you’re likely to find a similar program in your home state.

Private Land Access Programs: By the Numbers

![]()

30 Million Acres

Across the 27 states for which map data is available to onX, roughly 30 million acres of hunting lands are accessible on private land and leased public land. The total area of enrollments vary from year to year, as some landowners sign up and others exit. To determine the total acres enrolled in a single year, onX tallied the data that’s published by each state and program.

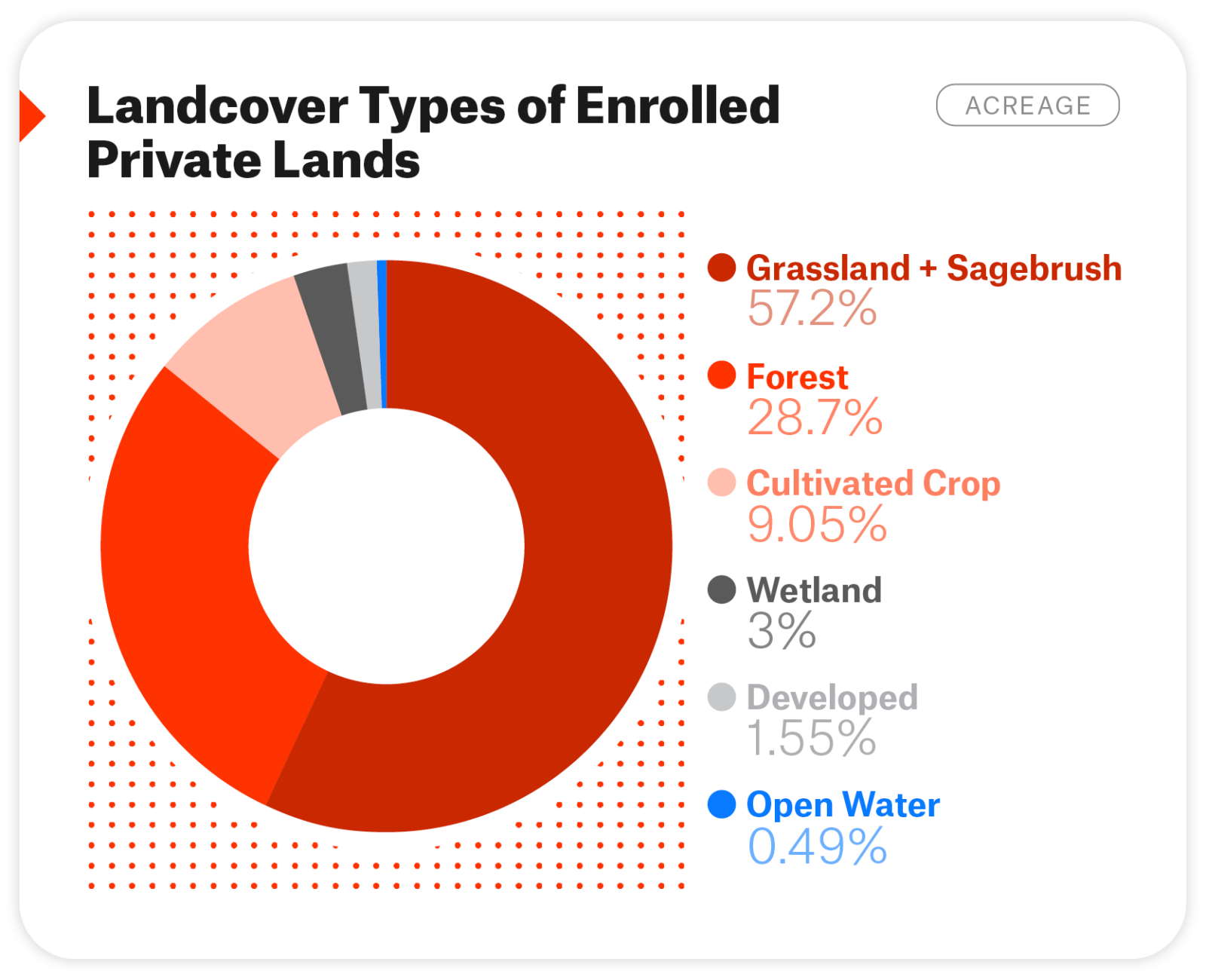

Landcover Types

More than half of all enrolled properties are in grassland and sagebrush country. Forests of all types account for 28.7%, while cultivated croplands make up less than 10%. Wetlands and open water account for a combined 3.5%. The small remainder are developed lands, like those used for energy production.

The diversity of landscapes offer habitat for a range of species, though the preponderance of grassland and sagebrush acreage does lend itself to birds and ungulates. Regardless, states won’t enroll just any piece of land; instead landowners apply and the property is evaluated by the agency that administers the program in that state to determine whether it has the right qualities for both game and hunter.

“We don’t typically enroll [land] we wouldn’t hunt ourselves,” said T.J. Walker, Assistant Division Administrator with the Nebraska Game & Parks Commission.

Once accepted, landowners also have latitude to impose certain species and usage restrictions, as well as specifying quotas, whether direct landowner permission is required, and other guardrails to ensure that hunting and hunters are managed toward both the agencies’ and landowners’ goals. State agencies typically provide liability protection and law enforcement on participating properties, another boon for many landowners.

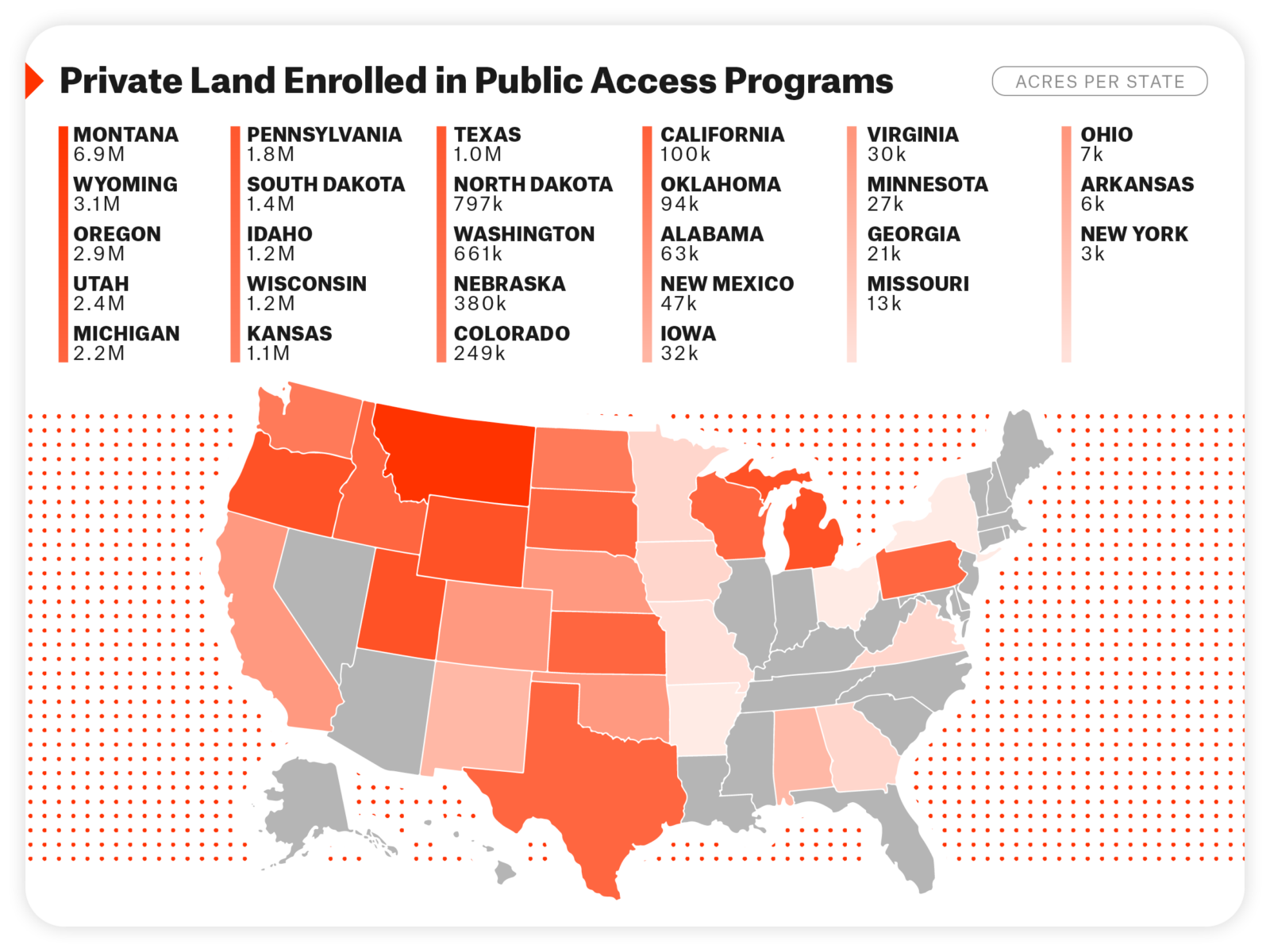

Note: States in gray either don’t have a private land access program, or the data displaying the locations of enrolled private lands in a geospatial format was unavailable at the time of publishing.

Western states, with large landowners such as timber companies and large-scale ranching operations, dominate the largest private access acreage offerings in the country, but considerable access through the Great Plains and Upper Midwest provide opportunities in regions with less public land available. Texas, in which less than 1 percent of its large landmass is publicly owned, has over 1 million acres of enrolled private access land.

In Kansas, which boasts the country’s oldest voluntary public access program, there are 4.5 acres of available private land per licensed hunter—some three times more acreage per hunter than is available on public land. In South Dakota, nearly 30 percent of huntable acreage in the state is via voluntary public access programs. In both Michigan and Wisconsin that number is 22 percent, critical access for states that both rank in the top five for most number of registered hunters with over half a million each.

Note that in general, New England states take an inverse approach to the rest of the nation, and consider private property open to the public unless specifically posted otherwise.

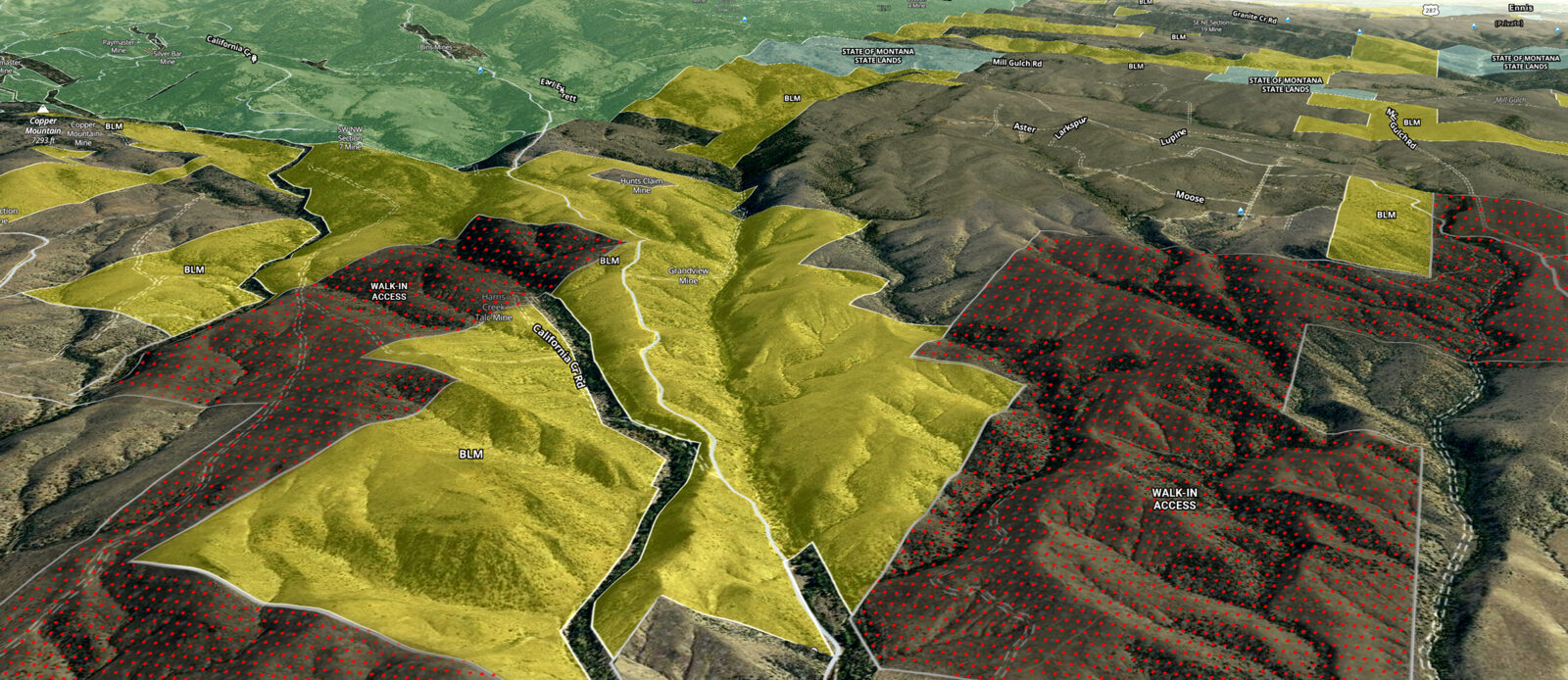

Unlocking Public Land … Temporarily

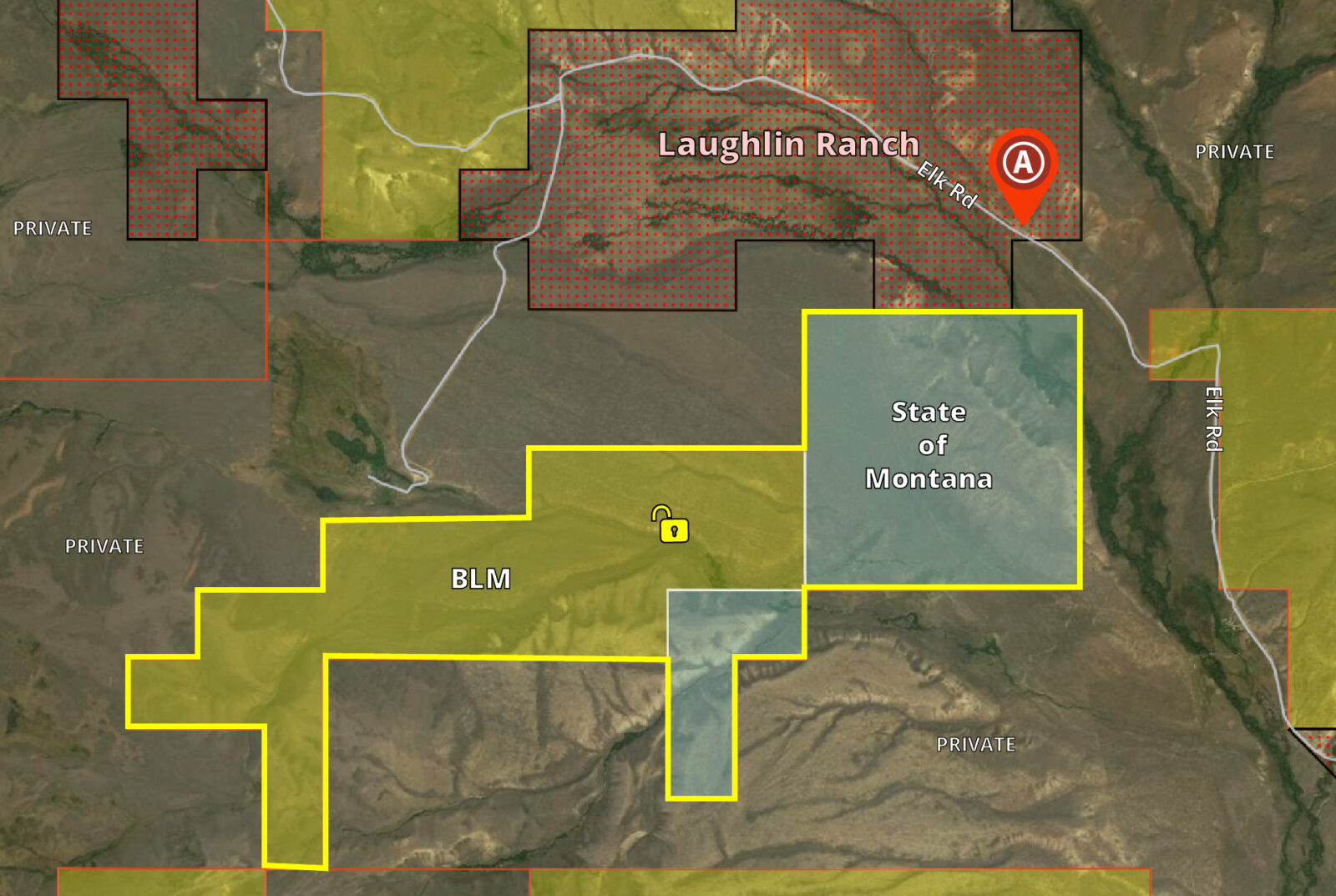

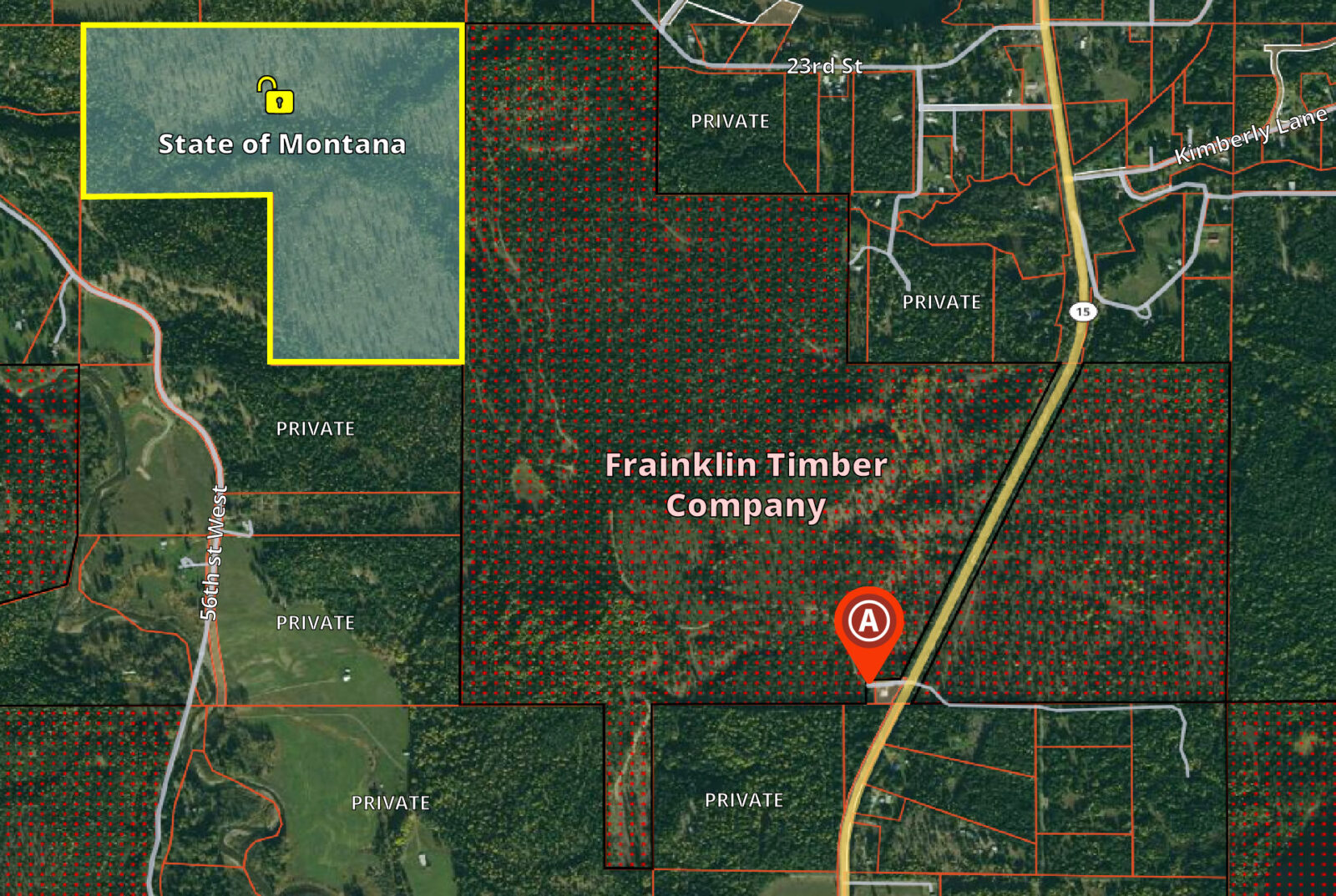

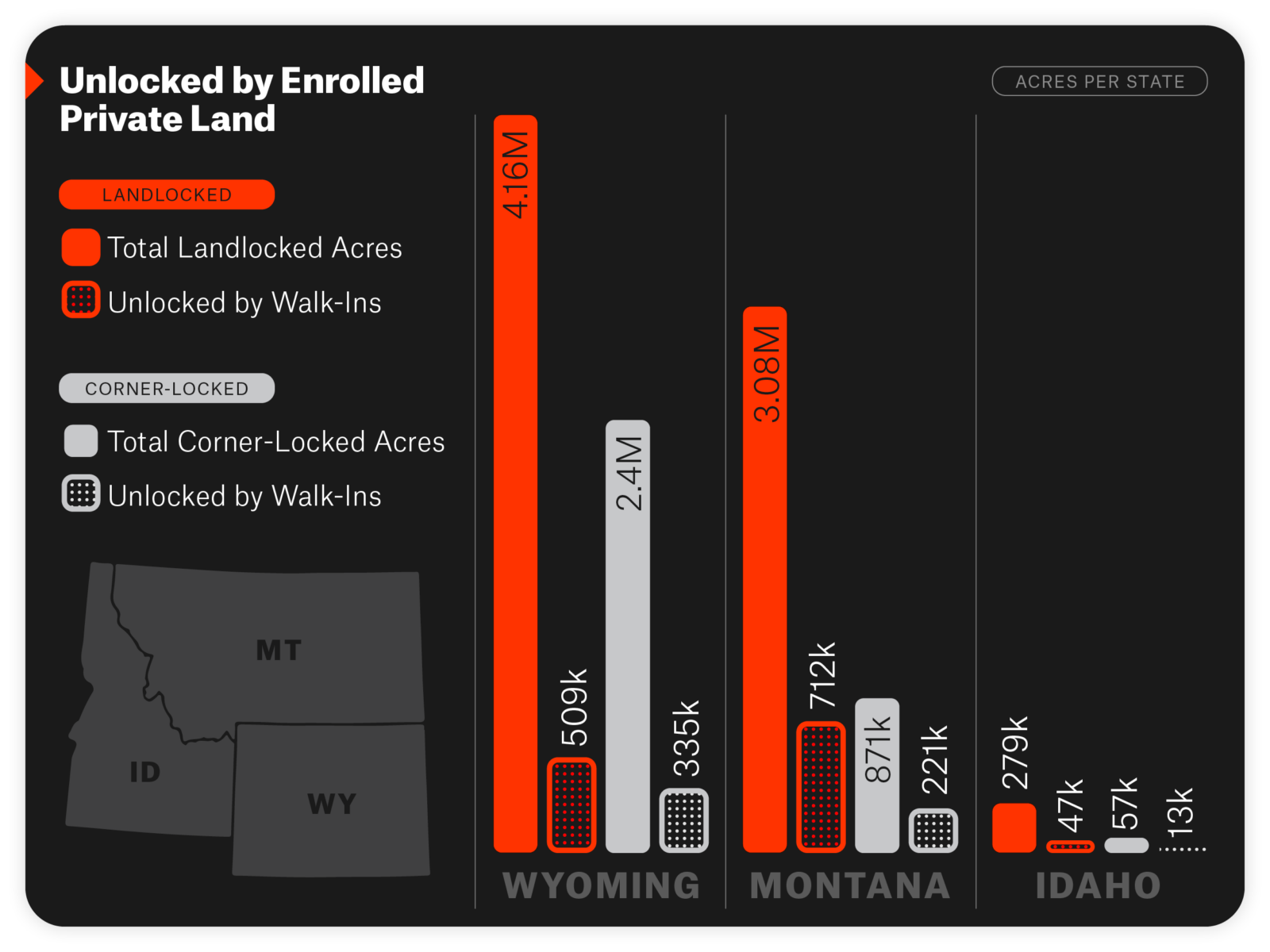

There are over 15 million acres of federal and state land in the West that are landlocked—inaccessible to the public because they’re either surrounded by private land (landlocked) or only touch other public land at the corners (corner-locked).

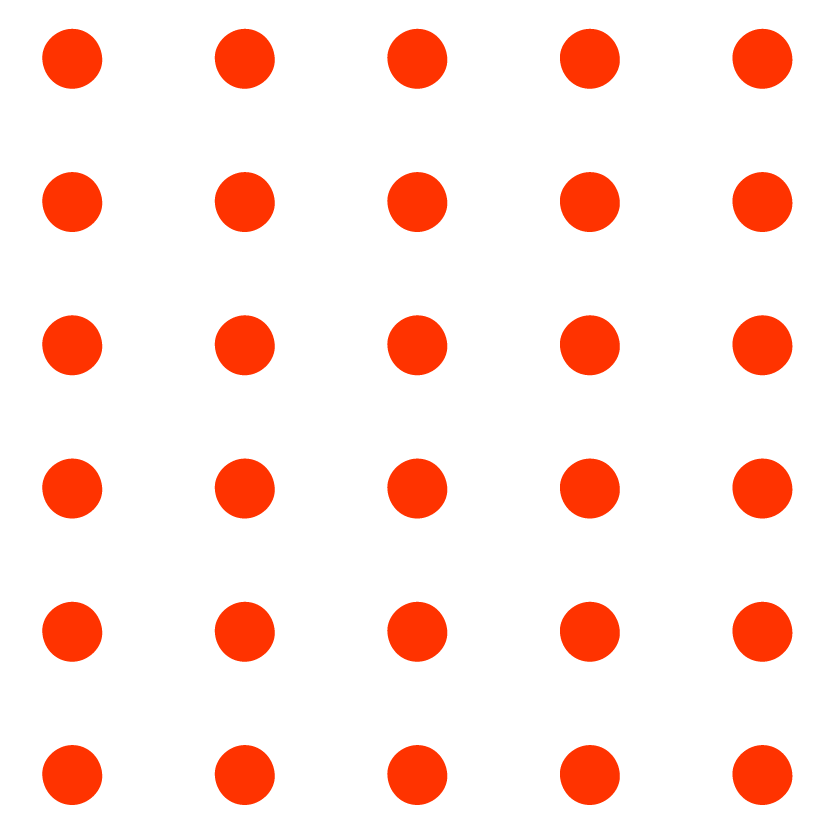

![]()

Voluntary public access programs help open those parcels during the window of time the landowner has enrolled their property by effectively creating a “bridge” to the public land.

In three western states with large amounts of landlocked acreage—Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming—voluntary access programs unlock more than 1.26 million acres of public land. That’s roughly 17 percent of the total landlocked area in those states, which would otherwise be completely inaccessible year round.

![]()

By enrolling their land, landowners give back hunting access on public land in areas that would otherwise be exclusive to the surrounding landowners. However, it’s important to read and understand the regulations on a given property, as some enrolled properties restrict where or how to access adjoining public land.

Why It Works

Passion, Incentives, and Support Push Landowners to Enroll

onX asked officials at state fish and wildlife agencies and departments of natural resources what is working in their state’s private land access programs, and we spoke to landowners who welcome hunters onto their properties each year.

Whether driven by a love of hunting like Idaho’s Tom and Jeannie Billington or drawn in by incentives—or, more likely, a combination—private landowners report a range of reasons for enrolling. Incentives vary from state to state, but most programs offer some combination of lease payments, habitat improvement projects, liability protection, and law enforcement on enrolled properties. Landowners also may be looking for help reducing the number of deer or elk on their property, especially when income-generating crops are at stake.

In Michigan, a program specialist in the state department of natural resources said “We receive many positive comments from landowners related to the flexibility of the program and how they enjoy sharing their land with hunters. Sharing their land ranks as more important than the lease payments for many participating landowners.”

For Billington in Idaho, who views the requirement for hunters on his property to get permission as critical, it’s as much about his own knowledge of who’s on his fields as for the accountability it instills in hunters.

“I can tell them what areas have cattle, and to stay out of that area. ‘Here’s some good country to hunt, here’s a good place.’ You’re in control of their sites they hunt on,” he said. “Youth also have to ask permission, and in doing that, they can be responsible for any damage or excuses. They’re held accountable. I just ask that they leave the access permission booklet in the mailbox when they leave so they don’t wake me up from my Sunday nap.”

— Tom Billington

The desire to provide access is a common theme with participating landowners, regardless of whether they’re meeting and greeting each hunter that comes on a property or leveraging the programs for oversight and administration of the access.

“[Participating landowners] like allowing public hunting on their land to contribute to South Dakota’s hunting heritage,” said Mark Norton, a program coordinator with South Dakota Department of Game, Fish & Parks. “Hunters are courteous and appreciative of the landowners, landowners appreciate that hunters can only walk to hunt the property, landowners are often busy during the hunting seasons and don’t have to stop work to grant permission to hunt.”

“Increasing public access for outdoor recreation benefits wildlife populations, mitigates agricultural damage and helps build relationships between landowners, hunters, and Game and Fish,” said Kelly Todd, Wyoming Game and Fish Department Access Yes coordinator. “We extend our gratitude to the landowners for their partnerships and the sportspersons for their donations to make these access opportunities possible for all to enjoy.”

![]()

Threats to Success

Bad Behavior, Tight Budgets, and Finding Willing Landowners

![]()

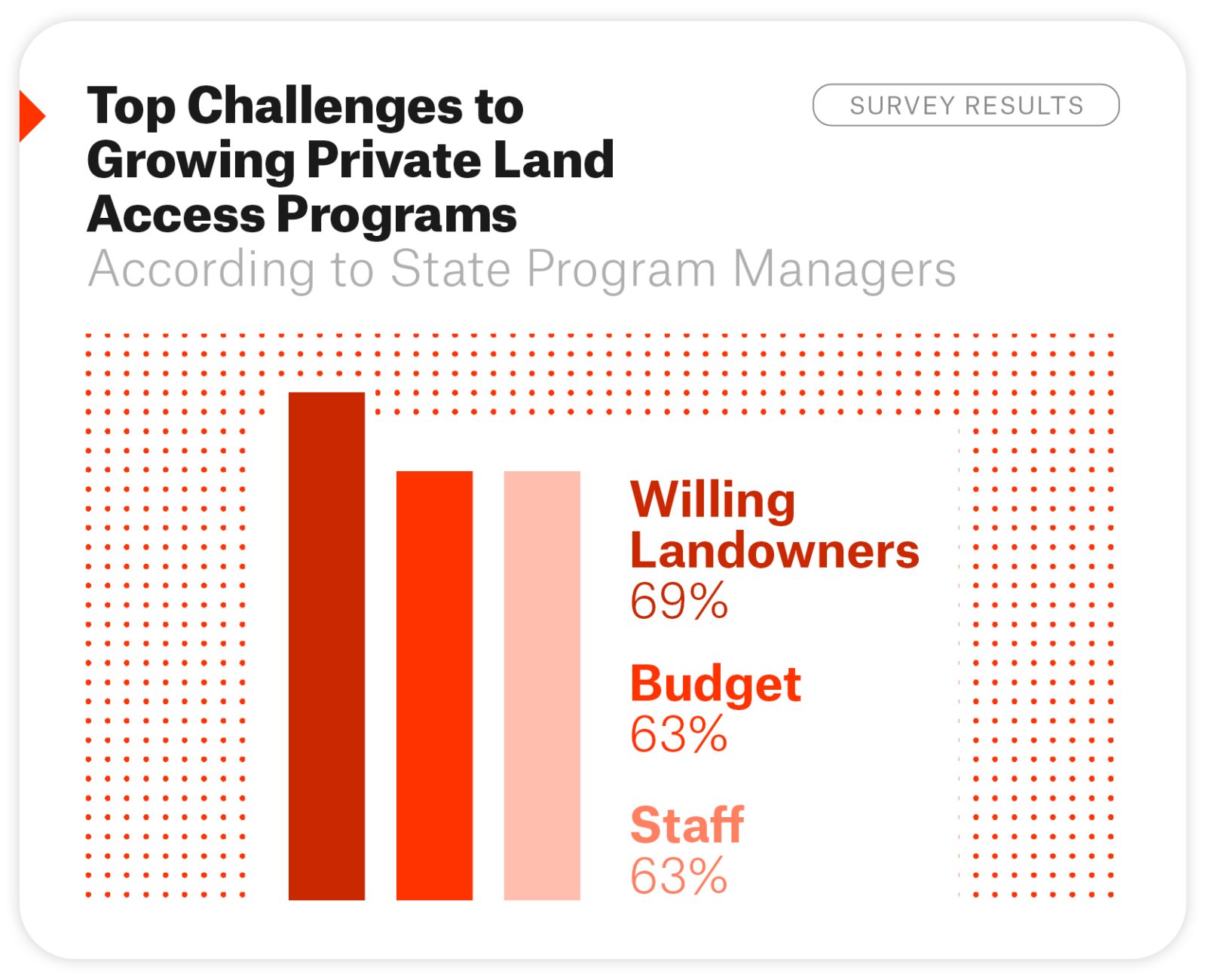

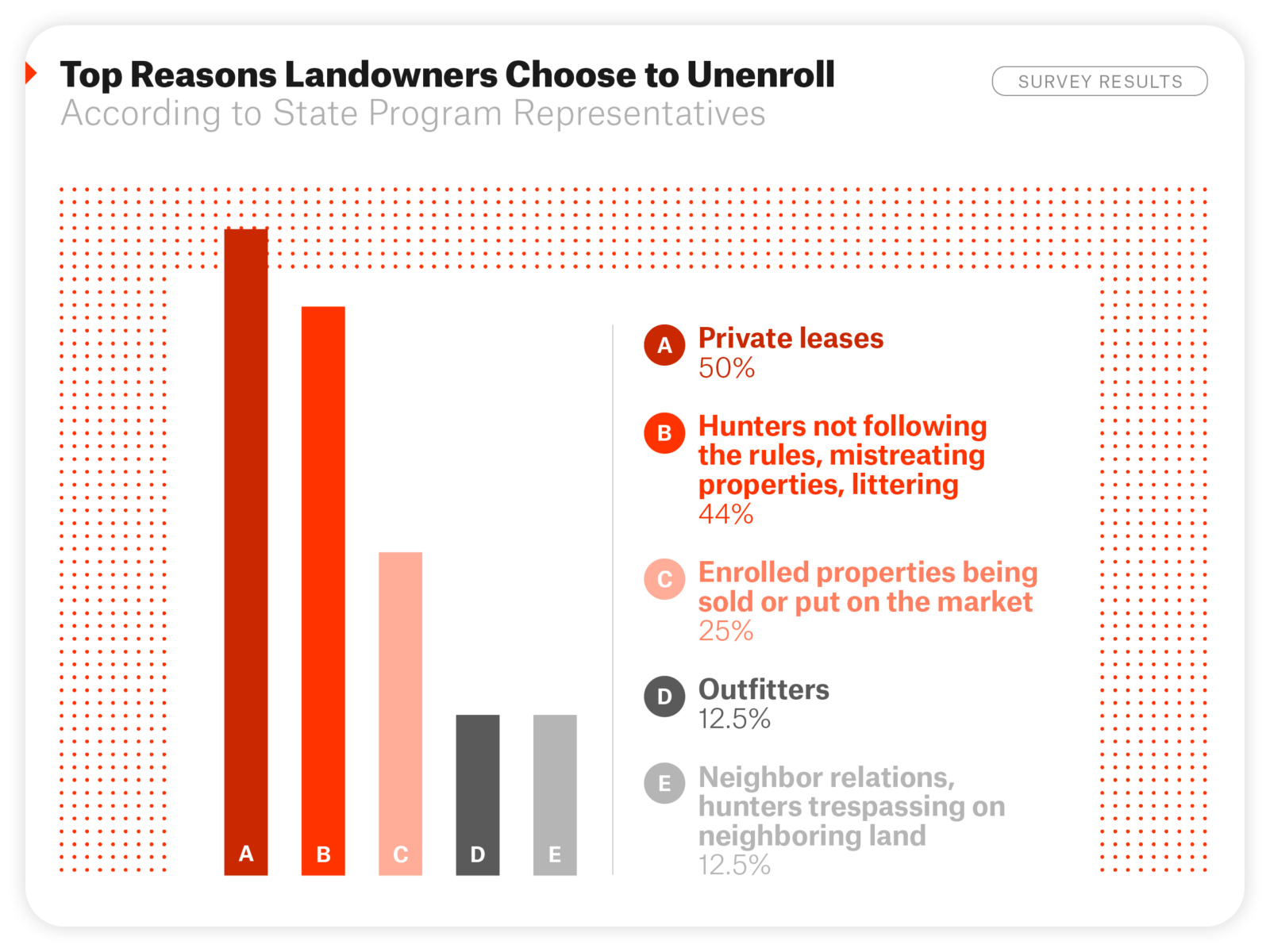

Despite the seemingly win-win scenario for landowners and hunters alike, headwinds remain. Future funding sources for incentives and staffing are uncertain, finding new landowners to enroll as population and demographic shifts leave agencies searching for participants, and, critically, the threat of a few bad apples ruining it for everyone looms large every year.

Agency staff in several states mentioned mistreatment of private land by hunters as a concern, and some emphasized the need for more personnel to patrol enrolled lands.

In Arkansas, the private Ross Foundation has made providing outdoor recreation access a key component of its philanthropic mission for the people in the public land-limited southwest part of the state. After nearly 40 years of opening private lands to the public, the foundation has picked up a few strategies to help mitigate bad behavior. A modest $20 annual fee to access the wildlife management areas it manages in concert with Arkansas Game and Fish has had a considerable impact on the level of respect.

“People become real respectful and cognizant of these types of arrangements if they are paying a nominal fee for the access. If it’s a free lunch program, they expect a place at the table and tell you how to do it,” said Ross Foundation Land Manager Mark Karnes, recalling contentious public meetings years ago in which some locals were incensed at new restrictions around vehicular use on the properties.

“A candidate for state legislature asked me what I thought gave me the right? I looked at him and said, ‘it’s private property and we’re the landowner.’ The meeting ended pretty quick after that.”

Another challenge is the need to strike a balance between promoting the hunting opportunities offered by these programs, but not to the point that properties become over-crowded, especially those near population centers. A concern that could be mitigated with more enrolled properties.

Using information provided by about one-third of the states we reviewed, back-of-the-napkin math suggests that for every enrolled landowner, there’s anywhere between eight and 230 hunters using their properties, with most states seeing 45-60 hunters per landowner. Of course, the size of enrolled properties varies from a few acres to tens of thousands of acres, so this is not a measure of hunting pressure, but it is an indicator of the supply and demand for access.

When we asked the state agency representatives what the biggest hurdles are to growing their private land access programs, the signals were clear: finding willing landowners, budget to increase incentives, funding to improve staffing, and to a smaller degree, the availability of suitable wildlife habitat that could be enrolled.

Recruiting and Retaining Landowners?

They Have Other Options.

![]()

These programs are not going to make landowners rich, nor are they intended to. In Montana, for instance, payments to landowners are explicitly not for access, but rather to offset the various costs of the public hunting on private land. This can mean anything from fire protection and weed control to road maintenance and conservation improvements.

But if frustrated by bad experiences with hunters using the property, a lack of support from agency staff, or simply seeking higher monetary returns, landowners have options that threaten these public access opportunities to 30 million acres.

The simple fact is, private groups and individuals can offer more money per day of hunting as part of private leases or agreements with outfitters. For corporate landowners like timber companies, a few bad apples might be enough to simply lock the gates.

As one senior biologist put it, “There is a lot of competition for hunting rights on private lands in the South and we are fortunate to work with a lot of great private landowners who see the value in allowing public use of their land.“

Meanwhile, in the opposite corner of the country, Don Jenkins, a natural resource program coordinator with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, said, “We are losing some properties to private leasing. Idaho is growing, and it seems difficult to get new landowners to participate for various reasons. There are more recreationists competing for places to get outdoors.”

One environmental scientist summed up what many of the agency representatives expressed: “It would be helpful to enroll new landowners if we could increase the dollar per acre we can pay them.“

Critical Funding Up for Vote in 2023

To remain competitive, state and tribal government programs have to offer a range of incentives from habitat improvement projects and management assistance to law enforcement and liability protection. And whether it flows directly to landowners as cash incentives or pays for the staff to support program components, the success of voluntary public access programs comes down to dollars and cents.

![]()

In our review of landowner incentives among different states, the lowest lease rate we found was $2 per acre per year for agricultural land, and the highest was $30 per acre per year for high quality wildlife habitat. Some programs instead pay on the basis of hunter-days, the number of times hunters sign in to use a property for a day. Additional factors—such as how many days of the season a property is open, the total contiguous acres enrolled, the types of hunting allowed, location within a priority area, the completion of habitat improvement projects, and the number of years the landowner has been enrolled—can also add to the total payment a landowner receives.

Funding for these programs come from three sources, primarily. First is the Voluntary Public Access and Habitat Incentive Program (VPA-HIP) money nestled within the Farm Bill. The second is the Pittman-Robertson Act, which taxes sales on guns, ammunition, and archery equipment across the nation. Lastly, some states have opt-in stamps hunters can purchase or options to donate refunds from unfilled tags with revenue going directly to their state’s program.

The Farm Bill is legislation that Congress votes on every five years and allocates funding for the nation’s agriculture and nutrition programs. Tucked within it, VPA-HIP allows tribal and state agencies to apply for funding that they can then disburse to landowners allowing access and improving the habitat on their land.

Over the past decade, budgets for conservation programs through the Farm Bill have been slashed by over $1 billion. This year, the Farm Bill goes up for debate and must be reauthorized. Currently, there’s a bipartisan proposal on the table called the Voluntary Public Access Improvement Act which would bolster funding for VPA-HIP from $50 million to $150 million over the next five years.

“Our current program is dependent on the federal Farm Bill for funding and continued awards through NRCS (Natural Resource Conservation Service). We have received funding each time we have applied. Our current grant will run out next year. We are awaiting news of the next Farm Bill,” said a Wisconsin DNR Lands & Habitat specialist.

States are also considering upping the total amount they can pay to landowners—in Montana the cap leapt from $15,000 to $25,000 just a few years ago and in 2023 doubled to $50,000. That could make a real difference in keeping large landowners with popular access (Montana pays based on hunter usage, not per acre).

“With the old cap, we were having some landowners have … thousands of hunter days that they weren’t being compensated for,” Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Region 3 Supervisor Marina Yoshioka told Montana television station KTVH when the bill was signed. “It also makes Block Management [Montana’s voluntary access program] competitive with other opportunities that landowners have when considering access programs for their lands.”

How to Get Involved

If you value public access for hunting, encourage the local landowners you know to find out if their properties qualify for your state’s program. If you’re a landowner and believe in opening up access, consider enrolling your land. Another great step is to reach out to your federal representatives to share your thoughts on funding for VPA-HIP through the Farm Bill.

![]()

An easy step hunters can take that makes a difference is checking the box on hunting applications which asks if you want to donate to the state’s access programs. Hunters can also make sure they complete surveys from the wildlife agency in all the states they hunt in. This may seem like just another survey hitting your inbox, but the data collected is vital for planning, budgeting, and managing enrolled private lands.

And finally, being a good visitor on private lands is critical to keeping access open. “Hunters not following rules (trespassing on adjacent lands, driving on enrolled lands, not following posted rules, littering, etc.) is a leading cause of landowners opting out of the program,” noted a program specialist in Michigan. Simple things include following the regulations laid out by the state and the landowner. Picking up your shotgun shells, traveling on durable surfaces, and leaving gates as you found them are all a great place to start. If you really want to level up your game (we recommend you do), consider sending a card or gift to the landowner or sharing a photo of your harvest. All of these actions and more build a friendly and respectful relationship and one that could last generations.

Respect the Speckle

When you’re on private land, extra consideration goes a long way toward helping support voluntary access programs and the landowners enrolled in them.

![]()

Here are some ways to be extra respectful of this access:

Follow all landowner rules and restrictions.

Pick up shells and trash.

Don’t drive on wet roads.

Leave gates as you found them.

Thank the landowner with a handshake.

Send the landowner a card or photo of you and your harvest.

Paying It Forward Doesn’t Cost A Lot

Across more than half of the country’s states and spanning 30 million acres, a common thread among private landowners allowing the public to hunt their property is passion for access, wildlife, and hunting.

![]()

In Arkansas, the Ross Foundation takes its payments from Arkansas Game and Fish and passes them on, donating to other conservation organizations in the region such as the Arkansas Forestry Association, The Nature Conservancy, and toward specific quail restoration projects.

“These entities can leverage the dollar we give them in their own grant writing activities for matching funds,” said the foundation’s Karnes. “You can in some instances get three dollars for that one dollar in. These initiatives are really important to the future conservation of habitat in the Southeast.”

Idaho’s Tom Billington thinks about that idea of the public “renting” land in a much bigger philosophical sense.

“We get to be on this land, we never own it,” Billington said. “It’s in gratitude of my neighbors and my family that I grant Access Yes! to kids and vets.”

Or, put another way: “It’s a baton. We’re handing that baton of life on.”

To learn about the private land access programs in the places you hunt, follow the link below to our state-by-state resource guide.

onX extends sincere thanks to the state agency representatives and the landowners who contributed their perspectives, experiences, and knowledge to this report.