They say you shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth but that doesn’t apply to your freshly harvested deer. Many hunters may be familiar with the concept of inspecting deer teeth on the lower jaw to count them, look for wear, or check the number of cusps on the third tooth. If you’re not familiar with this method we’ll explain that shortly. However, there’s a different scientific method for deer teeth aging that can document a deer’s true age with remarkable accuracy, and it’s available to every hunter.

Counting Cusps, Deer Teeth, and Looking For Wear: One Way To Age Deer

Looking at deer teeth wear and quantity has been a method used to age deer for decades, and everyone from occasional hunters to wildlife biologists have used it for bragging rights and managing deer, respectively. Technically, it’s called eruption wear aging and it was developed by C.W. Severinghaus in 1949, but it’s never been completely reliable.

Young Deer

Eruption wear aging method requires looking at the deer’s row of cheek teeth on the lower jaw. If a deer has four teeth along the cheek (not including the front incisors) then that deer is a fawn (about six months old). If it has a fifth tooth it could be up to a year old.

In young deer, you can count the cusps of the third tooth (tooth number one is nearest the incisors). The first three cheek teeth are called premolars, and the back ones (numbers four, five, six) are molars. A cusp is the raised point on the crown of the tooth. However, in young deer, it will look like the tooth is divided into two or three sections. The Indiana Department of Natural Resources has a great visual guide to aging deer teeth this way.

A 1.5-year-old deer will typically have three cusps on the third molar and the sixth tooth will just start being visible above the gum line.

A cusp is the raised point on the crown of a tooth.

2.5-Year-Old Deer

As a deer continues to age, the third tooth becomes more uniform but also more worn. At 2.5 years old, the third tooth will come to have two sharp, permanent cusps and start to show staining. This staining is actually the dentin core (which is dark) showing through the enamel (which is white). Additionally, the sixth molar will have sharp, defined cusps.

3.5-Year-Old Deer and Older

At 3.5 years old, the deer’s back cusp of the sixth molar will show considerable wear, forming a concavity. Beyond 3.5 years, a deer’s fourth tooth will show more and more wear so its darker dentin color will be wider than the light-colored enamel. This wear continues on and on to the point at which deer over eight years old have shallow, completely smooth teeth. Texas Parks and Wildlife has a visual guide illustrating these age gaps with real pictures of deer teeth. It’s worth a look.

If one is solely looking at tooth wear, though, it can be easy to see why the technique isn’t so reliable. Deer eat different things in different places. A deer in the South munching on clover all day is expected to have better-preserved teeth than, say, a mule deer eating tough skunkbush sumac and mealy juniper leaves in the West.

Peering into a deer’s mouth for eruption wear aging can be useful in two ways. First, it can be done in the field, so it’s timely. Second, it’s somewhat reliable for deer younger than 2.5 years old. But for deer older than that it can be hit-and-miss, which is to say mostly it’s a miss.

Aging Deer Teeth Using Cementum Annuli

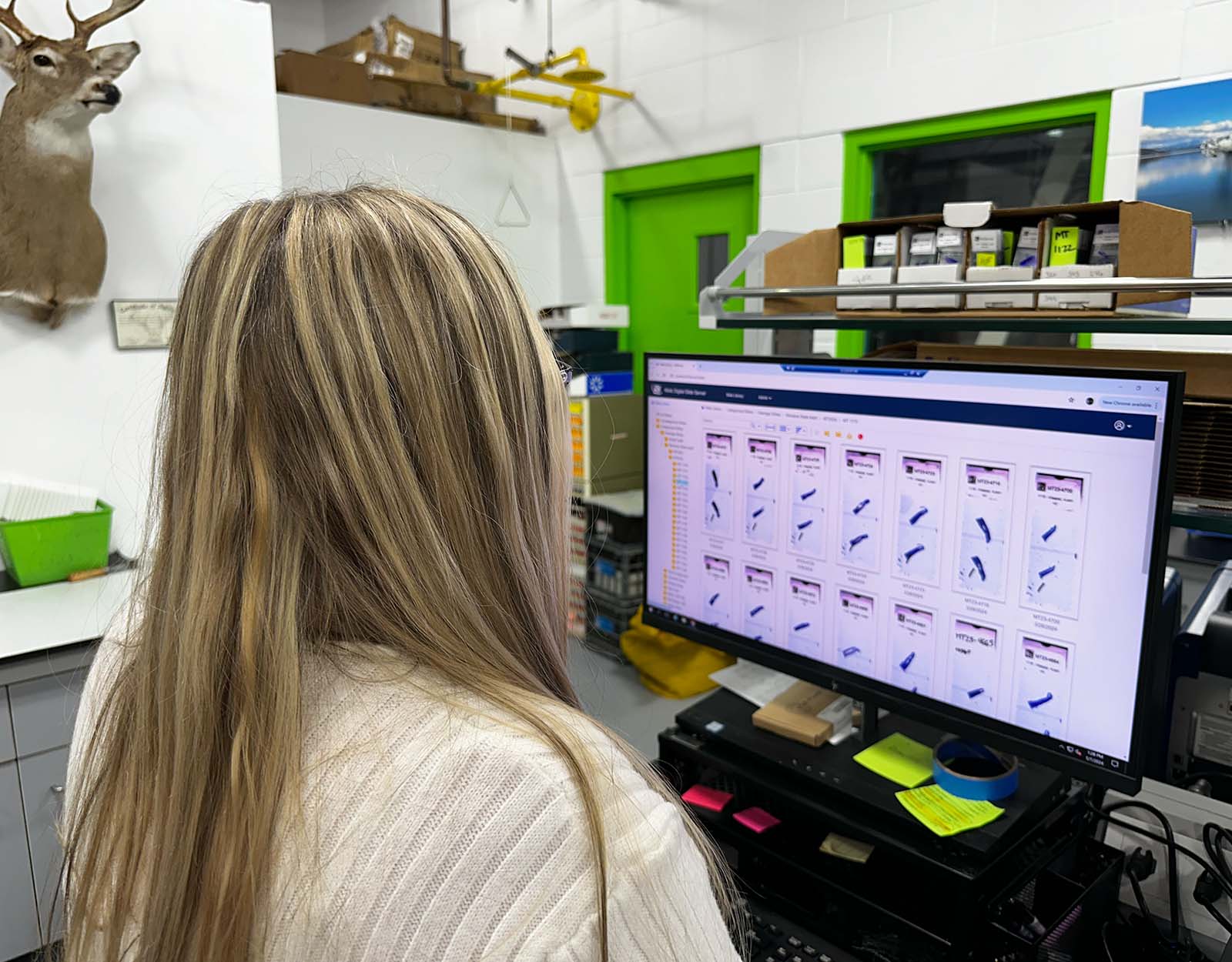

Heather Stevens owns and operates Wildlife Analytical Labs and DeerAge.com from her lab in Missoula, Montana. In her simple but meticulously laid out lab, housed in a white cinderblock room with bright lime green accents and doorways, Stevens and her small team are among the very few in the world who do this commercially and they age tens of thousands of deer teeth annually. It’s a service used by state and federal agencies as well as the general hunting public.

“People are surprised how old their deer is,” says Stevens. “They think it’s a five- or six-year-old and it’s really nine or 10. They’re very surprised.”

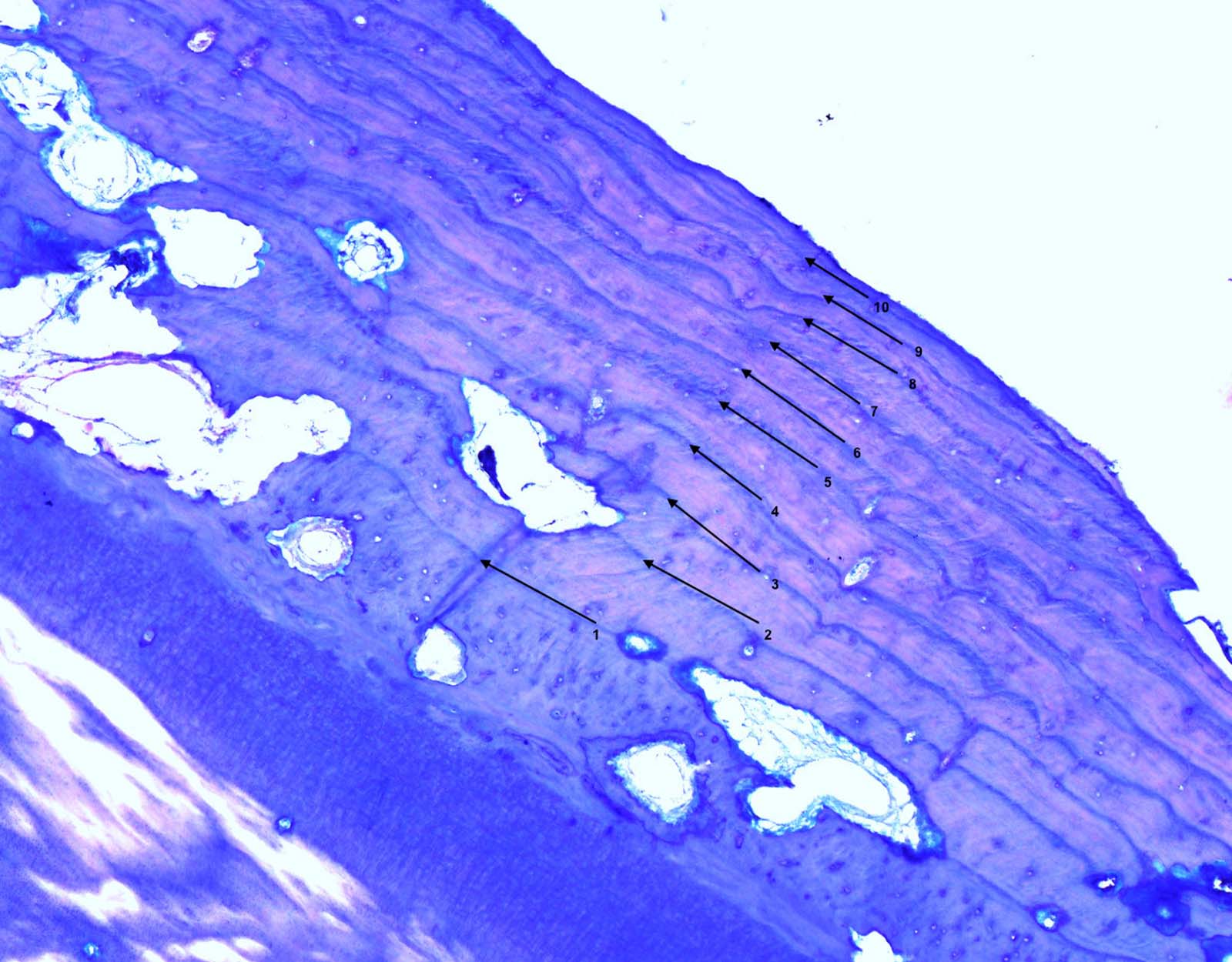

Cementum Annuli Aging

The procedure used at DeerAge is called cementum annuli aging and it’s based on the cyclic nature of cementum deposits on the roots of deer teeth (all mammals, actually), which results in a pattern of rings in the tooth. For lack of a better comparison, it’s akin to counting the rings of a tree that’s been cut down to determine its age. The annuli are the “rings” and the cementum is the space between those rings. A new ring will appear each new year in a deer’s life as it heads into fall.

Cementum was first discovered microscopically in 1835. It’s a substance in mammals’ teeth that is softer than enamel and dentin and occurs between the two. It’s been used for aging deer since Canadian scientist Frederick Gilbert published a paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management in 1966.

Numerous studies have compared cementum annuli aging versus in-the-field eruption wear aging. Stevens likes to cite a Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks study. The study found that looking at tooth wear for aging was 62% accurate for mule deer, 43% for whitetails, and only 36% accurate for elk. In contrast, the science-based method Stevens uses was 93%, 85%, and 97% accurate for mule deer, whitetails, and elk, respectively.

Other studies have yielded similar results. One study from the Wildlife Research Institute in Texas found that tooth wear accuracy of known-age bucks (2.5 years old) was 43%-51% accurate, but if you expanded and accepted the fact that a deer could be one year older or one year younger than its actual age then the accuracy improved to 87%. Explained another way, you’d be right most of the time that a deer was between 1.5 and 3.5 years old simply by eyeballing its teeth.

A Deer’s Life History

When accuracy counts, however, science comes into play. “I can even tell when a deer has had an injury,” says Stevens. Stress in animals can prevent them from growing a healthy layer of cementum gap between the annuli. Stevens has been able to recreate the reproductive history of female bears by looking closely at the cementum gap, seeing annuli lines nearly stacked on one another the year a female has raised cubs.

“I’ve started paying attention every time I get [a tooth like this] one,” says Stevens. “I’m like, this deer had to have had something wrong with it. I will call the person who submitted some of them and ask, ‘Was there anything wrong with your deer?’”

The replies she gets have ranged from that deer having had a broken leg it was dragging around or having an old arrow sticking out of it. Stevens can then say, “Yep, that was around year three when that happened. Because the stress causes the lines to become very wavy and strange and stack on top of each other.”

How To Age a Deer: The Cementum Annuli Aging Process, in a Nutshell

The cementum annuli aging technique is a multi-step process that requires specialized equipment. And one of the main differences between this process and looking at wear is that cementum annuli aging looks at entirely different teeth.

The first teeth a fawn gets are its front incisors, so these are the ones Stevens asks people to send in (actually, you’re asked to send in two of them). It’s important that the entire tooth is submitted because it’s actually the root of the incisor that’s used, again highlighting a big difference between aging wear in the field and aging a tooth in a lab.

Through proprietary steps, these teeth are cleaned, boiled, turned to a gelatin-type substance, dyed, sliced lengthwise (not a cross-section like a tree trunk), and examined and photographed through a microscope. Then Stevens starts counting rings.

What causes annuli rings to form has been subject to debate. They do form over the late fall and winter months, so early scholars thought it was the stresses of food shortages or especially hard winters forming them, thus claiming this technique was not as sound as it’s portrayed to be. But this science-based method has been successfully used in animals from all parts of the world, including Africa where, at last check, there aren’t long, harsh winters. Stevens believes annuli ring formation has to do with the stress of the rut. “The does are under stress,” says Stevens, “and the bucks are under stress. Just think about the stress these animals are going through.”

Aging Deer Teeth: Why and When To Do It

In full disclosure, Stevens recommends that “if your deer is younger than 2.5 years old, you’re just going to waste your money” sending it to the lab. Deer younger than 2.5 can be pretty easily aged by counting molars.

“You can very easily follow one of these charts online, determine your deer’s age, and move on with life,” says Stevens with a smile.

“We have a lot of lease landowners and hunting clubs that are trying to manage herds on their property,” says Stevens, “so they’ll require a certain age bracket to be taken. They’ll have everyone who is hunting their land turn in teeth to make sure no one is taking ones too young. There’s a big management aspect to aging deer teeth.”

“There’s also the average hunter that’s been following the same deer for a while,” continues Stevens. “Maybe that person has a lot of trail camera pictures that’s coming on and off their property and they have a lot of history with that deer but they’re not 100% sure how old it is. Then it’s just really exciting to get that information.”

“Then we also get a lot of new hunters,” says Stevens, “or a kid’s first buck. You want to get a certificate to commemorate the hunt and see how old that buck was. That information can then be used to help age other deer on the hoof and learn what deer look like at certain age brackets in the area you’re hunting.”

But be warned: “Then it becomes just addictive because now you’re just excited, right?” says Stevens. “You start out wanting to know for this reason or that reason, but then pretty soon you can’t really stop aging.”

How Long Can a Deer Live?

Understanding that Stevens routinely gets to surprise hunters and wildlife biologists by sharing a deer, or elk, or moose, or bear, or even a mountain lion, is older than they thought it was, she shared some of the data she’s been collecting for years. It was surprising.

In her newest database that only stretches back three years, Stevens and her team have aged a 14.5-year-old whitetail buck from Texas (which the hunter named “One-Eyed Jack”), a 22-year-old whitetail doe from Indiana, a 21.5-year-old cow elk from Montana, a 20-year-old mule deer buck also from Montana, and a 22-year-old brown bear from Alaska.

When asked if results like these are anomalies, Stevens says, “It’s not rare.”

Details for submitting deer teeth can be found at DeerAge.com.