By Ryan Newhouse

Tradition is a funny thing. It implies an experience can be reliably repeated, bringing with it similar emotions and outcomes. But when exactly do traditions start, or end? Is it the act or the meaning behind the act that makes it the thing? For me, carrying on and calling something a tradition is not a necessity, but it can be a quilt into which shared experiences are stitched. Tradition can be a thing that both holds memory and warms us when we call upon it.

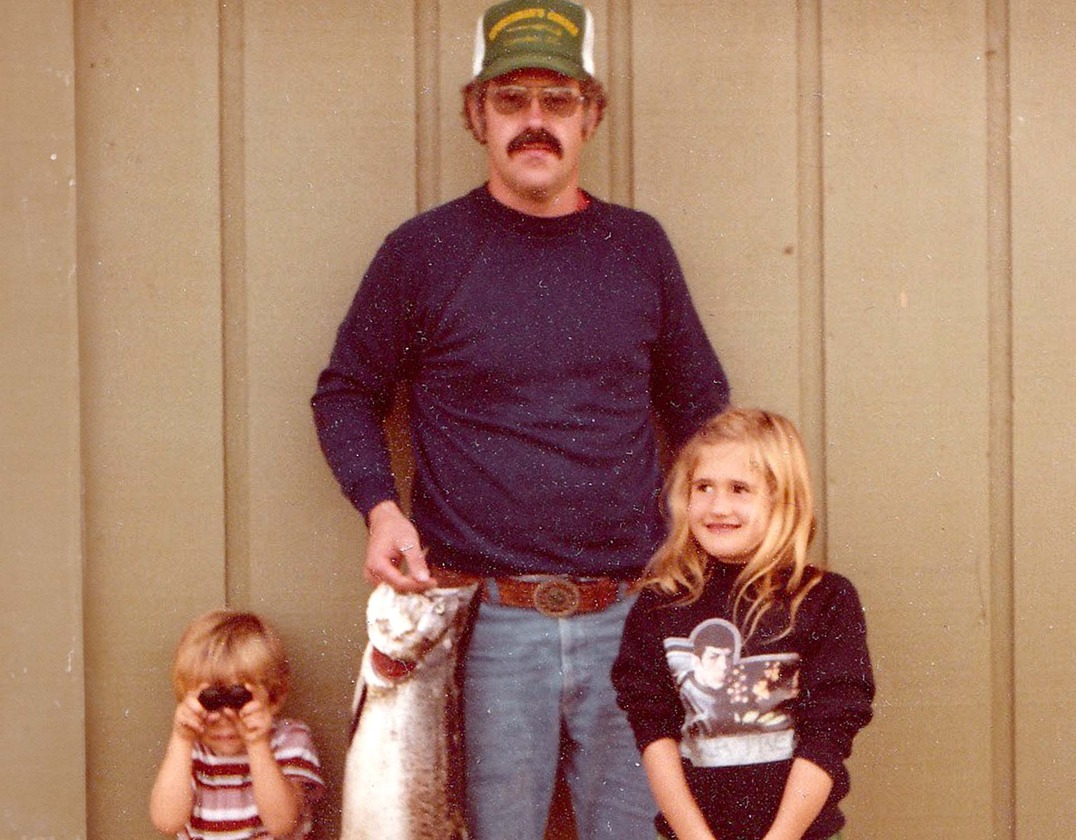

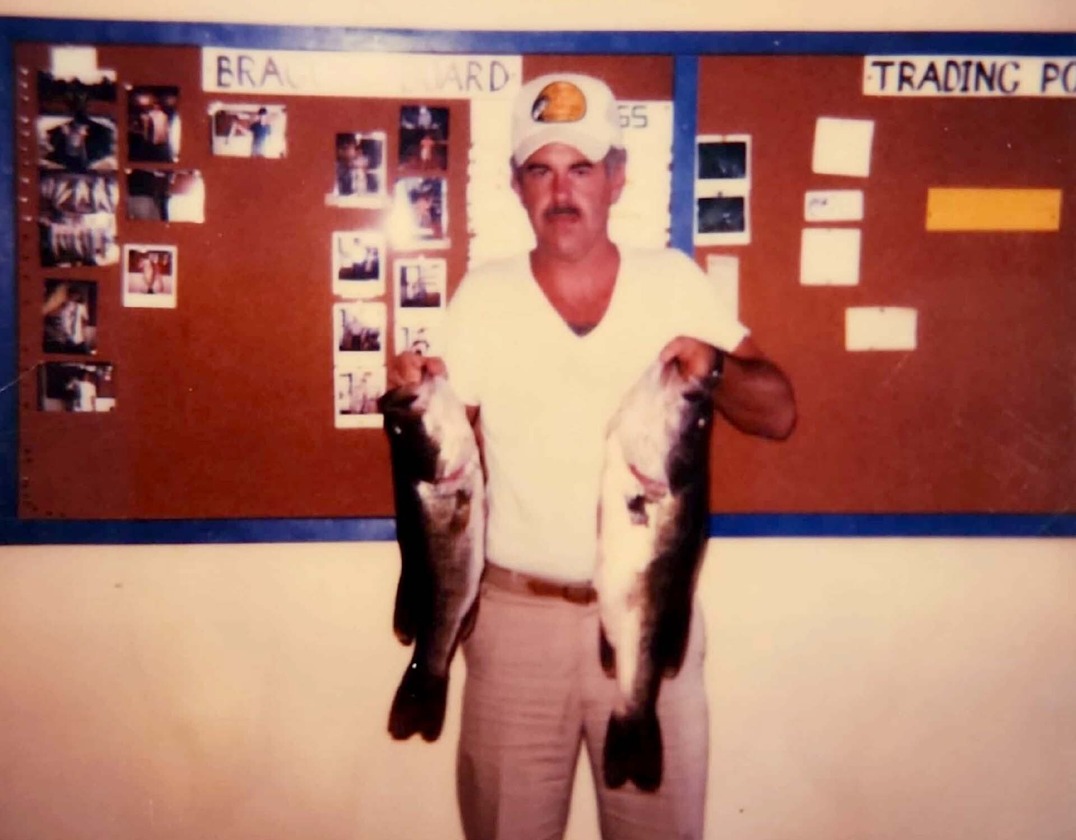

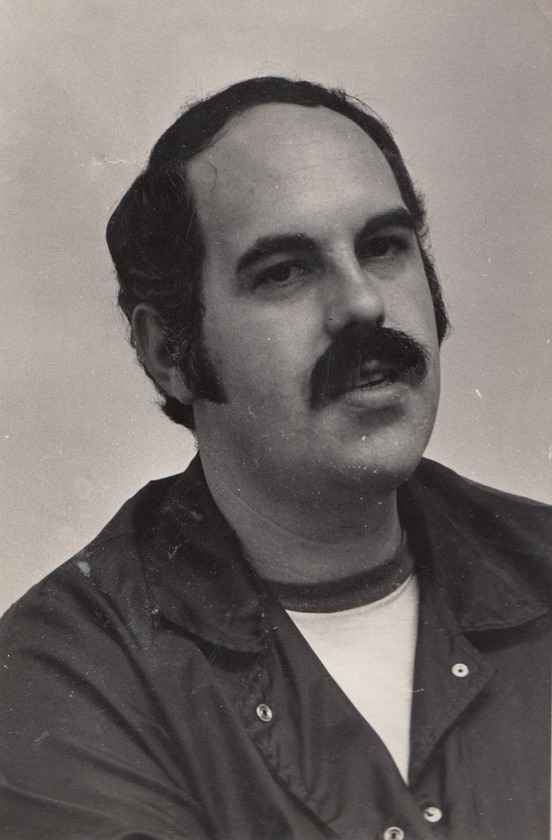

Hunting is a tradition for many. The opportunity of one was there for me and my father. He loved to hunt, especially for whitetails. He’d go every stolen moment he could take, whether for an evening sit, a full weekend day, or a week with his friends. I revered him as a harvester, watching him bring home ducks shot on the wing, lobster he caught by hand on a recent SCUBA trip, and largemouth bass so plump they could easily swallow his giant fist.

It was in his blood, as it is in mine.

He was a Long Island native who married a Southern girl, and while he still visited his mother’s 40-acre farm in upstate New York for occasional Thanksgiving day hunts, most of his time in the field was spent in homemade treestands or sitting on swivel-seat buckets in Georgia and then South Carolina, where I was born.

My father was also an amateur gunsmith and avid reloader. Reams of index cards scattered on our kitchen table held his secret formulas for every firearm he shot, most of which he built himself. I still have nearly every gun he made but most of his handcrafted loads are no longer in the world, just as my father, too, has left this life.

I can recall three, and only three, deer hunts with my father, though many squirrel and rabbit hunts and an untold number of fishing trips. As my memory serves, I had to convince him to let me go on those three hunts.

The first was in Georgia when I tagged along with him and his friend who had been partially paralyzed in a diving accident. My dad had built a custom gun rest that attached to his friend’s motorized wheelchair. After we set his friend up my father put me on a bucket seat on a dirt road in front of a very small clearing. He left me alone in a place I’d never been before. I vaguely knew that his friend was “that way” so don’t shoot there, but my father walked an opposite way before slipping off the dirt road and presumably into a treestand. I had absolutely no idea where he really was, only now not to shoot this way or that way.

After some neighboring dogs chased a doe into my one clear shooting lane, so close to me it halted and stared as I was clearly in its escape path, I was able to harvest my first deer. In my excitement I turned my head and called in the “this way” direction to my father, “I got one,” and the hunt was over.

My second hunt was from one of my father’s homebuilt stands set up next to a freshly cut cornfield in South Carolina. Instead of the buckshot-filled Browning 20-gauge pump shotgun I used for my first hunt, I was now carrying a bolt-action Browning .243, my Christmas present from the year prior.

After watching me climb the lumber rungs of his makeshift ladder to a platform more accurately measured in square inches than square feet, I sat on another swivel-seat bucket and watched my father saunter off and out of sight to his own stand, again with no clue where he was.

The only safety harness I had back then was my father’s words, “Don’t fall.”

It wasn’t long before a young whitetail spike moved along the nearest game trail to my stand and I was able to connect. After I was sure it was down I again yelled in the wind, “I got one,” in hopes it would find my father. It did and the hunt was over.

Our third and final hunt happened on my grandmother’s 40 acres in New York, two decades after I got that spike. My father lived there now, having taken everything he could from life and giving the very little he knew how to in return.

We walked familiar places, held familiar guns, and tried to have familiar conversations. The one time we sat and waited for a weary whitetail we sat apart. Him on a log and me under some oak. I knew where he was at least. Our light disappeared and the hunt was over.

My father passed days after my son turned two. Neither he nor his older sister really knew him. Partly because I moved out West about five minutes after graduating college and partly because I had not yet reforged a relationship with him I helped break. In the small window of time where I had kids and he was alive there were two questions I never asked, one I knew I never could—What’s it like to be a father? How can I be a good one?

When my kids asked me to go to the woods I would take them. They were too young to hunt but they could witness what I was doing. Dutifully, they would at least try a bite of the dishes I would make from animals they often saw hanging from trees in our yard or from rafters in the garage. Once my daughter took interest in helping me dissect a venison heart.

As kids, which they still are, I take them camping, boating, fishing, and to swim in storied rivers like the Blackfoot to catch its crawdads. I bring them on airplanes and very long car rides to show them different places and trees that are foreign to them.

My son has a taste for the woods and what can be harvested from them. And if he could fish every day for the rest of his life I think he would. He’s a crack shot on pine squirrels and whittles a mean stick for fire-roasted marshmallows.

Last year was the first year he could hunt deer, at age 10, thanks to our state’s Apprentice Hunter program. Kids as young as he was can hunt as long as they are accompanied by a certified Mentor. In this case, and hopefully in life, I am my son’s mentor.

There is a difference when hunting for oneself and when helping others hunt. Suddenly you want to know precisely where the animals might be and the paths of least resistance to get to them. You want there to be some modicum of certitude to the hunt so the fun of it shines through. At least that was my thinking when I thought of taking my 10-year-old out for last year’s youth hunt.

Him and I hunting together was the start of something new. We’d set out and camp and hunt and build fires, if not memories. We’d hunt public land, but I wasn’t sure where until one blessed friend shared a Waypoint where there were sure to be whitetails.

When I phoned the warden for that area days before we were to make camp and asked if there was any recent bear activity he told me no, “but expect them.” I asked if we should expect mostly black bears and he said, “I wouldn’t say ‘mostly.’”

The first day we got on deer, just as my friend promised, but we couldn’t connect. The next morning a moose sauntered by as we sat under a Ponderosa pine. We rested midday back at camp. So after a day-and-a-half we had nothing tangible to show for our efforts, just a moose encounter, one startled grouse, and a hundred “what if” questions.

For our final effort we’d return to the same Ponderosa for an evening sit. With less than an hour of shooting light left the consensus was to pack up and maybe have time to chase one more squirrel with a .22 before the day was truly done.

Moments into our walk out we spotted two does. “There,” he said. I had trouble finding them in my binoculars at first, but my son knew what to do: get settled on shooting sticks, make sure he had a clear shot, and be doubly sure of his target. He mounted the Browning .243, the same gun given to me by my father when I was just a year older than my son, and just as I found the deer in my binos he was targeting the shot rang out.

My son confidently took his first deer, dropping it at 100 yards,

He did not have to tell me that he got one. I was right there with him.

Our first of many hunts might be over, but my son and I know there will be more. We’ll both look forward to the next season, and the one after. We’ll plan together, scout together, and make camp together. No need to convince me to have him by my side.

As a father, I wonder about my kids. What will they be like? What will make them happy? How can I both protect them from and teach them what the world is capable of?

When I phoned my uncle to tell him that my father had passed away he told me what my father would often say to him on days they hunted together: “There’s nothing better in life than sitting under an oak tree with a can of beer and a very accurate rifle.”

Hunting, it seems, has become a tradition in my family. It has allowed me to spend time with my son, adding more fabric to the quilt I will pass on to him one day. But really I know that carrying on this tradition, like any we share and repeat, is simply an opportunity to love our children the best we can.