State-managed programs that provide public access to private lands are a great solution to manage wildlife populations and create hunting opportunities. They also help improve access to landlocked public lands (as we highlighted in our 2019 report, Inaccessible State Lands in the West, on page 13). These programs have become increasingly popular in recent years and most states have implemented some type of state wildlife agency-sponsored program.

Montana’s Block Management Program

State agencies have long realized the importance of landowners and landowner relations as a solution for wildlife management and access challenges. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) Block Management program has been doing this important relations work, and more, for over 25 years. The program now boasts nearly six million acres of private land made accessible to hunters, and over 1.1 million acres of public land are made more accessible through Block Management Areas (BMAs).

In Montana, over three million acres of public lands are inaccessible because they are surrounded by private parcels. We call these landlocked lands. At onX, we were curious how many acres of Montana’s landlocked public lands were opened annually to hunters by the Block Management program. Jillian J., the geospatial analyst dedicated to our access initiatives, compared our landlocked data for Montana to the BMA data, and determined there are 618,330 acres of landlocked public lands accessible through the BMA program that would otherwise be off-limits to hunters. That’s a huge success for public access because that is over 20% of the state’s landlocked lands.

An Interview With Montana FWP

We were also curious to learn how this impressive program began. So we asked Jason Kool, the Hunting Access Bureau Chief for Montana FWP, about the history and the “why” behind our home state’s unique BMA Program.

onX Founder Eric Siegfried: Can you explain the history of the Montana FWP BMA program?

Jason Kool: Block Management started in the mid-1980s by landowners working together with FWP field staff to improve hunter and wildlife management on ranches and farms locally. Additionally, landowners saw a philanthropic need to provide their “city cousins” a place and opportunity to get out in nature and recreate. This initial localized effort was then expanded significantly through the 1995 Montana Legislature and thus the 1996 hunting season. The Legislature authorized FWP to provide tangible benefits to private landowners as an incentive, compensating for the impacts of allowing public hunting. There have been lots of changes over time through various legislatures, but in general, the hunter management piece, complimentary hunting licenses for participating landowners, and monetary compensation for hunters’ impacts has remained.

In Montana, the private landowners work with FWP to set their property rules–which is why each of Montana’s nearly 900 BMAs have specific rules regarding species, hunting dates, parking, access routes, and gaining permission.

Siegfried: What inspired the Block Management system?

Kool: Block Management as we mostly know it today was the result of House Bill 195 in the 1995 legislative session. The concept for a statewide program that provided compensation for hunter day impacts, a free license for landowners, and hunter management came from the originating landowners as well as through the work of the Private Land/Public Wildlife Advisory Committee (PL/PW) established in 1993.

The 1994 PL/PW report to Governor Racicot problem statement suggests, “The long-term viability of Montana’s wildlife resource and hunting heritage is threatened. Landowner/outfitter/sportsperson relations have become increasingly strained over the past several years. Landowners feel victimized, helpless to control increasing game populations and they feel their contributions to wildlife habitat are overlooked. Sportspersons are concerned about diminishing access to private and public land for hunting opportunities. They view this as a threat to the long-term viability of wildlife management and Montana’s hunting heritage.”

Hence the creation of a statewide program designed to help landowners manage wildlife and manage hunters and their associated impacts as well as provide a way to foster hunter/landowner relationships. Our 2019 BMA survey suggests 72% of enrolled cooperator/landowners believe relationships with hunters have improved because of BMAs. Additionally, 78% believe hunter behavior has been improved or greatly improved because of the Block Management program.

Siegfried: Where did the idea for walk-ins originate from?

Kool: I’m not sure where the idea for a public-private partnership came from. I know many states have walk-in programs, but Montana is different. BMAs are landowner-centric and landowner-driven and more hunter management/wildlife-driven than typical walk-in programs. Hence the need to get permission to hunt a BMA. This permission comes in the form of hunter-administered permission (Type 1) or someone else administering permission (Type 2). Only a handful of Montana’s 890+ BMAs have “no permission required” to hunt the property. The remaining BMAs have rules, hunter limits (if applicable), and permission requirements as set forth by the landowner and in accordance with FWP program guidelines.

Siegfried: How are the landowners incentivized?

Kool: Landowners receive tangible benefits in the form of hunter management services, a complimentary sportsman license (or non-resident big-game combo license), a free subscription to our department magazine, and monetary compensation in the form of a per-hunter-day impact payment. Hunter management services are provided by over 30 FWP seasonal positions as well as full-time staff in the form of patrolling BMAs, developing and installing signage, and developing maps and rules for each BMA.

Specific to monetary compensation, landowners receive a $250 enrollment payment, up to $13 per hunter-day impact payment, and a 5% weed management contract bonus. The hunter-day payment is figured so that landowners choose when and what hunters may hunt on their enrolled lands. It is important to note this is an impact payment as opposed to a payment for access. In Montana, the BMA program doesn’t pay for access. It pays for the anticipated impacts on the land from allowing that access. In 2019, landowners received $6,113,538 worth of impact payments.

Siegfried: What is your favorite story of a successful recruitment of a landowner?

Kool: I’m sure our Regional Access Coordinators have better stories as they steer the ship locally, but for me, one of my favorite stories is when a new landowner purchased some property previously enrolled in BMA called and asked, “How do I remove these signs?” I spoke with them about the benefits of the program and they ended up working with our Regional staff and enrolling thousands of acres that would’ve been otherwise inaccessible to the public.

Siegfried: What does the public get?

Kool: The public not only gets the opportunity to go hunting on these enrolled private lands, but also a lot of access to inaccessible public lands for hunting. Almost six million acres of private land were enrolled in BMA in 2020. The other added benefit is the relationships that have been built over time between hunters and landowners.

Siegfried: How is the program funded?

Kool: From a combination of fees and licenses: primarily nonresident deer/elk hunting licenses, Native Montana licenses, as well as proceeds from the Super Tag Lottery, private donations and grants, and Wildlife Restoration/Pittman-Robertson funds. Residents contribute $2 of their base hunting license to the hunter access program.

Siegfried: What are formally-enrolled state lands, and how do they differ from other state lands?

Kool: Formally enrolled state lands are state lands that have legal public access, but access is limited or governed by BMA rules. This does not occur with any federal land. This is the result of a couple of things. First, the historic nature of BMAs originating in the mid-1980s when landowners could limit public access to their state land lease. These leases were considered part of the total ranch area enrolled in BMA, and there wasn’t a delineation made in peoples’ minds, like there is today, between what was private land and what was the rancher’s leased land. Secondly, there is a formal enrollment process outlined in Montana Administrative Rules. You can read more here.

Basically, by enrolling the leased state land, the landowner is also granting access to their private lands. This happened most often in southeastern Montana. If there was no formally enrolled state land, private land would be lost also. This is no longer a practice used by FWP today, but historic agreements and the benefits provided to the public dictate some BMAs will have formally enrolled state land. It will be indicated by signage posted on the ground as well as the PDF maps/rules produced by FWP for each BMA.

Siegfried: What resources are required to administer the program?

Kool: For this program to be successful it takes a collective team approach. From an FWP perspective, the program wouldn’t happen without landowners offering the opportunity, FWP staff to implement all the necessary facets of the program, and the hunters who buy the hunting licenses to compensate for the impacts of hunting on the landscape.

Annually, approximately 150,000 maps, 26,000 BMA access guides, and over 25,000 BMA signs are printed for public distribution. Six Hunting Access Program Coordinators, with assistance from area biologists and wardens, oversee and provide regional guidance and help to negotiate contracts, produce informational materials including maps, supervise seasonal staff, develop materials, and respond to the needs of hunters and landowners. Additionally, approximately 35 seasonal BMA technicians help set up, sign, patrol, monitor hunter compliance, and then dismantle the BMAs across Montana each hunting season.

Program administration includes time spent by myself with assistance from a variety of Helena staff who are responsible for approving contracts, payment coordination, the release of licenses and magazine subscriptions, hiring and equipping seasonal positions, and providing direction and coordination of regional activities.

For enforcement, six full-time warden positions are funded through Hunting Access Program funding sources. Portions of these positions are allocated statewide to game wardens who patrol BMAs for hunter compliance with the rules. FWP biologists and other wildlife staff also play a crucial role in landowner relations and evaluating the game and habitat opportunities available on properties considered for enrollment.

Siegfried: What else should the public know about the program?

Kool: This program, as it’s known today, is 25 years old (at the end of 2020). We have about a 95% re-enrollment rate, but that can change annually.

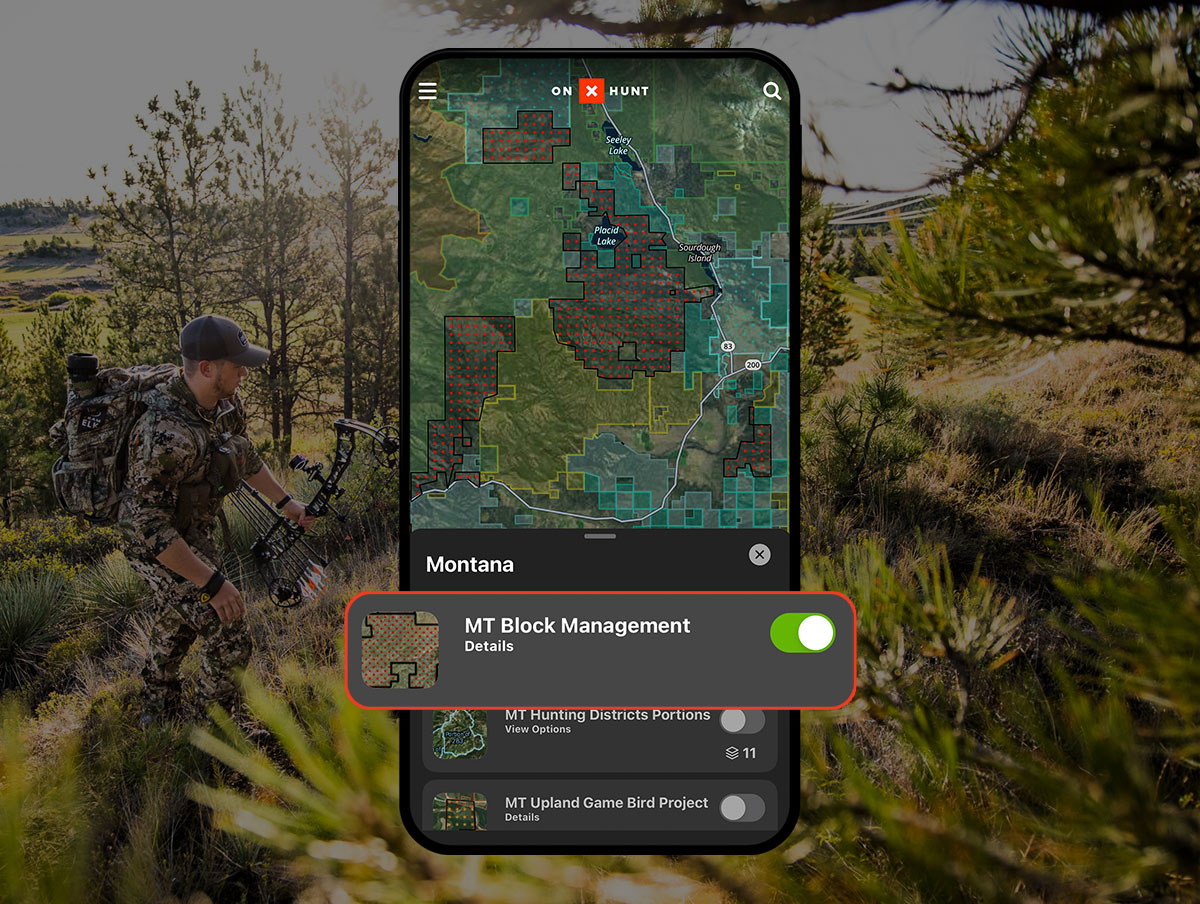

Because it is landowner-driven, it’s very important to get the individual BMA maps/rules PDFs, as each of the nearly 900 BMAs could be different in a variety of ways. Just because a hunter sees a BMA doesn’t mean there is a standard set of rules or travel routes–hence the importance of the FWP-produced BMA map/rule PDFs.

Siegfried: This is great information, Jason, thank you! And many thanks to the entire Block Management team for 25 years of impactful work for hunter access.

If you’re out on one of these BMA’s this upcoming season, please remember to be thankful for the landowners and the BMA officials who make this access possible.

Hero photo: Captured Creative