CWD. Three letters that have become part of most hunters’ lexicon in the past 20 years. Most of us know that those three letters are short for chronic wasting disease, a neurodegenerative disease resulting in irregular behavior, loss of body condition, and eventual death. And while it’s easy to get caught up in a doomsday scenario regarding CWD (we’ve all seen the “zombie deer” headlines, haven’t we?) it’s not all bad news. State and governmental organizations around the country have formed CWD task forces that are working diligently to manage, mitigate, and—in states yet to have a positive test—prevent the spread of CWD.

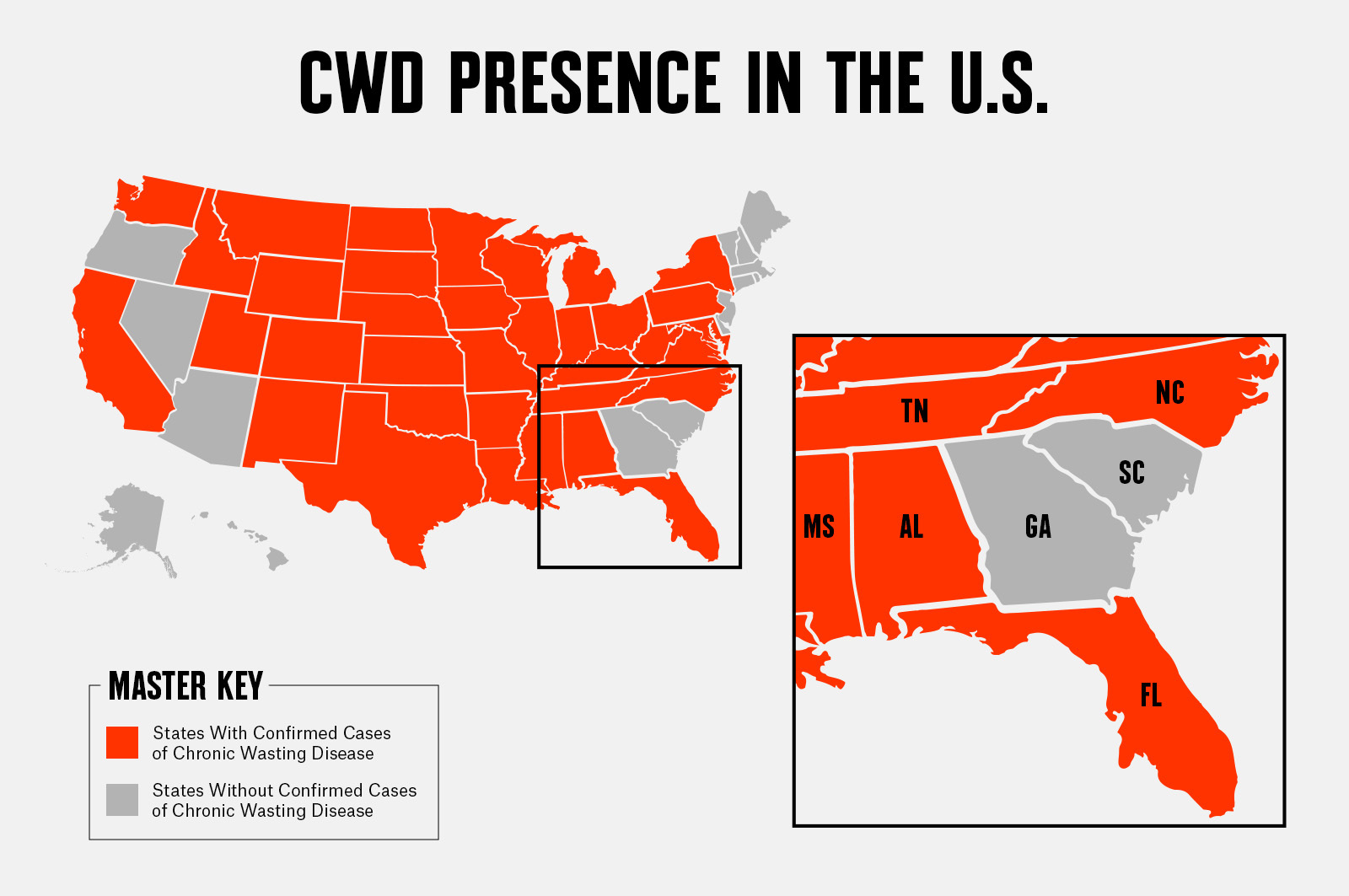

In the southeastern United States, two states have yet to present any positive test results for CWD. Both Georgia and South Carolina are ready for the day it happens, but the two states have seen success with prevention and educational efforts to ensure hunters, processors, and taxidermists know what to look for should a diseased deer present, and how they should report the deer if—when—the time comes.

Charlie Killmaster, a State Deer Biologist and the Deer Management Assistance Program Supervisor for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, notes that for the state of Georgia, “The single biggest factor why we don’t have it here is that Georgia has never had a captive whitetail breeding industry.” In 2005 the state banned the importation of live deer, and South Carolina has done the same. Of course, even though there is no formal captive deer breeding industry, it doesn’t mean his team hasn’t caught people trying to do so illegally. It’s an effort that involves consistent reinforcement by local law authorities and game wardens.

Why is the lack of a captive deer breeding industry a factor? The National Deer Association (NDA) notes that contagions (prions, in this case) spread through urine, feces, saliva, blood, semen, and especially via live deer. Importantly, there is no vaccine or cure. When deer are concentrated together, there is naturally a cross-pollination of many of these factors.

Think of kindergarten kids in a schoolroom—it just takes one sick kid to start spreading the cold around.

The Basics of CWD

CWD itself is caused by prions, abnormal proteins that change normal proteins in an animal’s cells, resulting in a concentration of more abnormal proteins. It’s a long-burning disease: According to the United States Geological Survey, chronic wasting disease in animals has an extended incubation period averaging 18–24 months between infection and the onset of noticeable signs. Eventually, the abnormal proteins accumulate in both the lymphatic and central nervous systems, causing degeneration and eventually death by “wasting away.”

The NDA notes that most hunters will never see a deer showing classic symptoms of CWD, as animals typically die from a variety of indirect causes before exhibiting evidence of the disease. CWD has proven to be 100% fatal and is found in most species of the deer family (cervids) including elk, moose, mule, and white-tailed deer. It was first observed in captive deer in Colorado in 1967, and the first infected wild animal was an elk in Rocky Mountain National Park in 1981.

Now, in 2024, CWD has been found in 34 U.S. states, six Canadian provinces, and other countries including Korea, Finland, Sweden, and Norway. Species testing positive have ranged from whitetail deer, red deer, mule deer, moose, elk, and reindeer. Safe to say, CWD is here to stay. Scientists across the world are working on research to learn more about the disease, how it spreads, and how to combat it. This USGS map from June 2024 shows the distribution of CWD in the U.S. and Canada, with noted concentrations in several states including Pennsylvania, Kansas, Texas, and Wisconsin.

While scientific research is ongoing, state agencies are working to manage and mitigate the disease within their deer populations. And states that do not already have positive cases—such as Georgia and South Carolina—are working to ensure they have a plan for the day CWD does cross the border.

Planning for the Prospect

Monitoring and learning from CWD is a constantly evolving process. Killmaster notes, “I’ve been in this position going on 19 years now, and have watched CWD march across the Eastern states and the Southeastern states. Throughout, I’ve been in very close communication with my cohorts in the Southeast, and had the benefit of watching what works and what doesn’t work for all those years. It’s put us [the state of Georgia] in a fantastic position; 15 years ago we would have reacted differently than we would now with those learnings.”

He notes his response team has seen trial and effect with various CWD management programs, and they’re able to adapt and tweak their own state’s response plan using that information. It’s a collaborative effort state-to-state; he and his Southeastern counterparts get together twice a year to discuss strategies, and have regularly scheduled CWD calls.

If and when CWD is found in the state, Killmaster and his team have a battle plan in place. They have worked through tabletop exercises, boiling down their intensive 30-page master plan to a one-pager that they’ve shared with the public. Examples of action to be taken when CWD is discovered in Georgia (or within five miles of the state line) listed in the one-pager plan made available to the public include:

- Establish a disease management zone in each county within a five-mile radius around the positive sample.

- Sample intensively within a one-mile radius to determine prevalence and geographic extent.

- Samples will be collected from hunter-killed deer at self-serve freezers placed around the management zone. Other sampling methods may include sharpshooting, issuance of special permits, and testing road-killed deer.

- If local deer populations are over-abundant (e.g., over 50 deer per square mile), encourage increased harvest through regulation.

- Identify, sample, and quarantine any high-fence enclosures (deer farms involve GA Dept. of Agriculture) inside the management zone.

- Implement deer carcass transport restrictions in the management zone. The only parts approved for transport are boned-out meat, hides, skulls or skull caps with antlers attached and all soft tissue removed (velvet antlers are okay), jawbones with no soft tissue, elk ivories, and finished taxidermy mounts.

“That one-pager really covers everything for the public,” he comments. “We focus on not only what we’re going to do, but also on what we’re not going to do. We want to try to alleviate concerns people have had in other states—we’re not going to come in and annihilate the deer population.”

“If and when we do get it, it’s not going to be the end of deer hunting. If we stay on top of targeted removals and management, most people won’t really notice a difference.”

-Charlie Killmaster, State Deer Biologist and the Deer Management Assistance Program Supervisor for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources

Like most plans (and by necessity), Georgia’s CWD Response Plan evolves as the science changes. When CWD first came on the radar of many state agencies in the early 2000s, the states really didn’t know how to respond to it. They did what they could with the information they had. And as we learn more about CWD—as science reveals more about the disease—plans adapt.

Gino D’Angelo, Assistant Professor of Deer Ecology and Management at the University of Georgia’s Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, notes that a successful CWD Response Plan emphasizes partnership with landowners and hunters.

“They [Georgia DNR] know if it hits here, they’re going to need those people to manage the spread of the disease,” he reminds, before adding, “Georgia has always done a great job of this partnership in tabletop exercises to engage different partnerships across the state’s varied people and landscape. They’ve considered those differences in the plan.”

In a state where deer populations vary from 10 to 60 or even 100 deer per square mile in all manner of varied terrain from mountains to coastline, accommodating differences could be the key to success, and is an important part of any response plan.

Communication Is Key

But no battle plan is useful without a way to communicate it to the troops—in this case, the hunters, taxidermists, and processors in the field.

“We have a really fantastic communications team and it makes a big difference,” Killmaster notes of his Georgia Department of Natural Resources colleagues. “We do a lot of social media for awareness, and have a strong social media team.” (Browse through the team’s Facebook posts for a taste of the communications.) He spends a lot of time communicating with processors and taxidermists throughout the hunting seasons and the subsequent CWD testing process, and is working with compatriot D’Angelo on a survey to gauge the effectiveness of these communications. Studies such as this help the team adapt their communications and address concerns about how CWD—if and when it’s found—might impact an individual’s businesses.

D’Angelo notes that Georgia’s communications efforts pay off. “What I see here in Georgia is a very high satisfaction with the state agency and the relationship they [residents] have with the agency. There’s a very high level of trust in the information,” he shares. “Georgia DNR is always concerned about keeping constituents as close partners. There are plenty of public meetings and educational campaigns. They listen to the public about seasons, bag limits, etc., and therefore the public supports them.”

It’s a case study in positive interaction between state agencies and hunters, processors, and taxidermists—a state trying to understand what their people want and how they can manage the resources accordingly.

Surveillance and Testing

For preparation and management, readily accessible online tools and updated information about restrictions and guidelines for hunters are key, as are open communications with processors and taxidermists. Good relationships with the latter two have been helpful in getting the state testing samples in an expedited fashion, as the industry professionals are willing to provide the samples and are a concentrated “passage” for harvested deer.

Georgia uses a strategic testing process using a Cornell University model which helps identify high-risk areas where CWD testing should be more concentrated.

“One of the main things we’ve done is really brought some better science to our surveillance approach,” shares Killmaster. “With this Cornell risk-based surveillance, we went in together with Alabama and South Carolina and worked with Cornell to build this model out. It’s helping direct our sampling efforts to where they’re the most efficient and the most likely to find it early. That testing led to the discovery of CWD in Tennessee; the model identified some gaps in their sampling and when they tested, they found it.”

The educational component of CWD is a fine line to walk unto itself. We’ve all grown tired of the doom-and-gloom “zombie deer” headlines, and it’s easy as a hunter to just tune it out when there’s enough chaos in the world right now anyway. But the state of Georgia seems to have found a good mix: keeping their hunters informed frequently about proper carcass transport and testing, partnering with taxidermists and processors, and working to understand what their hunters already know and what information is lacking.

It’s a moving target, but an important one.

If and When CWD Comes to New States

So what happens when CWD is found in a new state? With the disease now present in 34 states, the spread may seem inevitable. Lindsay Thomas, Jr., Chief Communications Officer for the National Deer Association, notes he often sees social media panic when the disease is found in a new state. And like most things on social media, that panic tends to be overblown.

“That panic gradually calms down as people realize they go hunting for a season and still have deer,” he notes. “We want people in those areas to go about business in a little different way: testing, helping us keep deer density in balance with habitat, and also to keep hunting. Engage and become an active participant. Help manage CWD in your area.”

It’s better to find CWD early—while the disease still has a low rate of prevalence in the deer population—and manage it, than to not test and only catch it once a high percentage of a region’s population is infected. Testing is a good thing, and keeping low prevalence is equally good. The science changes daily as we learn more about the disease, such as the fact that predatory cats can destroy prions, as noted in this article penned by Thomas Jr., where he writes:

“Chronic wasting disease prions are the Chuck Norris of infectious materials. Incinerating them at 1,112°F will only slightly degrade their infectivity, and you must hit 1,800°F to destroy them. They are just fine left out in the environment for years, outside an animal host, without losing infectious potential. They can even survive a trip through the guts of coyotes and crows and still infect deer. It’s tough to kill something that isn’t really living to begin with.

But we can now lengthen the short list of things that destroy CWD prions. A trial with mountain lions and a separate study with bobcats—neither of which appear to be susceptible to CWD infection—found only about 2% to 3% of the prions that entered the front ends of these cats made it out the back ends.”

Some states are managing very well, Thomas Jr. notes. He notes that Missouri has CWD present “all over” the state, but they have kept prevalence in the single digits using good management techniques, many of which are detailed here with the Missouri Department of Conservation. The state is actively managing its CWD zones to manage low prevalence, which means sustainable harvest in the future. He adds that the disease is so slow-spreading that once it’s found, states must work to keep deer density balanced with habitat in the given area. Keep deer harvest regular and keep testing… all the things can help manage for a long time. Buy time for science to find better solutions.”

“It’s not the end of the world if you find it,” Thomas Jr. reminds. “We can live with it; you can continue hunting and we can have healthy deer. You can continue. You can’t just sit with it; you have to work to keep prevalence low.”

What might a solution look like? It’s an abstract word right now in CWD circles.

“A solution may not be what we envision when we think about that word,” Lindsay Jr. asserts. “It might not be a vaccine; it might be something as simple as you can kill prions with bleach when you’re cleaning your gear. It might be the bobcats and mountain lion news. The University of Wyoming and the University of Alberta conducted a vaccine trial which provoked an immune response in elk… it’s not ‘we have a vaccine now’ news, but it’s something. It’s encouraging.”

He notes he’s also encouraged by the overall public response, and hunters’ willingness to trust their local wildlife agencies. The more we can communicate and work together, the better the odds for CWD management become. And for deer hunters across the country—across the world—that’s good news.