We’ve all heard or told the joke that the best place to shoot a deer is as close to the truck as possible, but knowing where to shoot a deer is the foundation of ethical hunting and ensuring the recovery of your downed animal.

This guide will help you determine the best shot placement on a deer in nearly every situation you might ethically shoot while hunting with a rifle or a bow, including shooting from a treestand and compensating for angles.

TL;DR: The best place to shoot a deer—whether with a bow or rifle—is the heart-lung area just behind the front shoulder. This vital zone ensures a quick, ethical kill. Broadside and quartering away angles offer the best shot opportunities, while frontal and head shots should be avoided. Study deer anatomy, understand your shooting angles, and practice from realistic positions like treestands for consistent accuracy. Use the onX Hunt App to map stand locations, visualize shot paths, and plan your next ethical harvest.

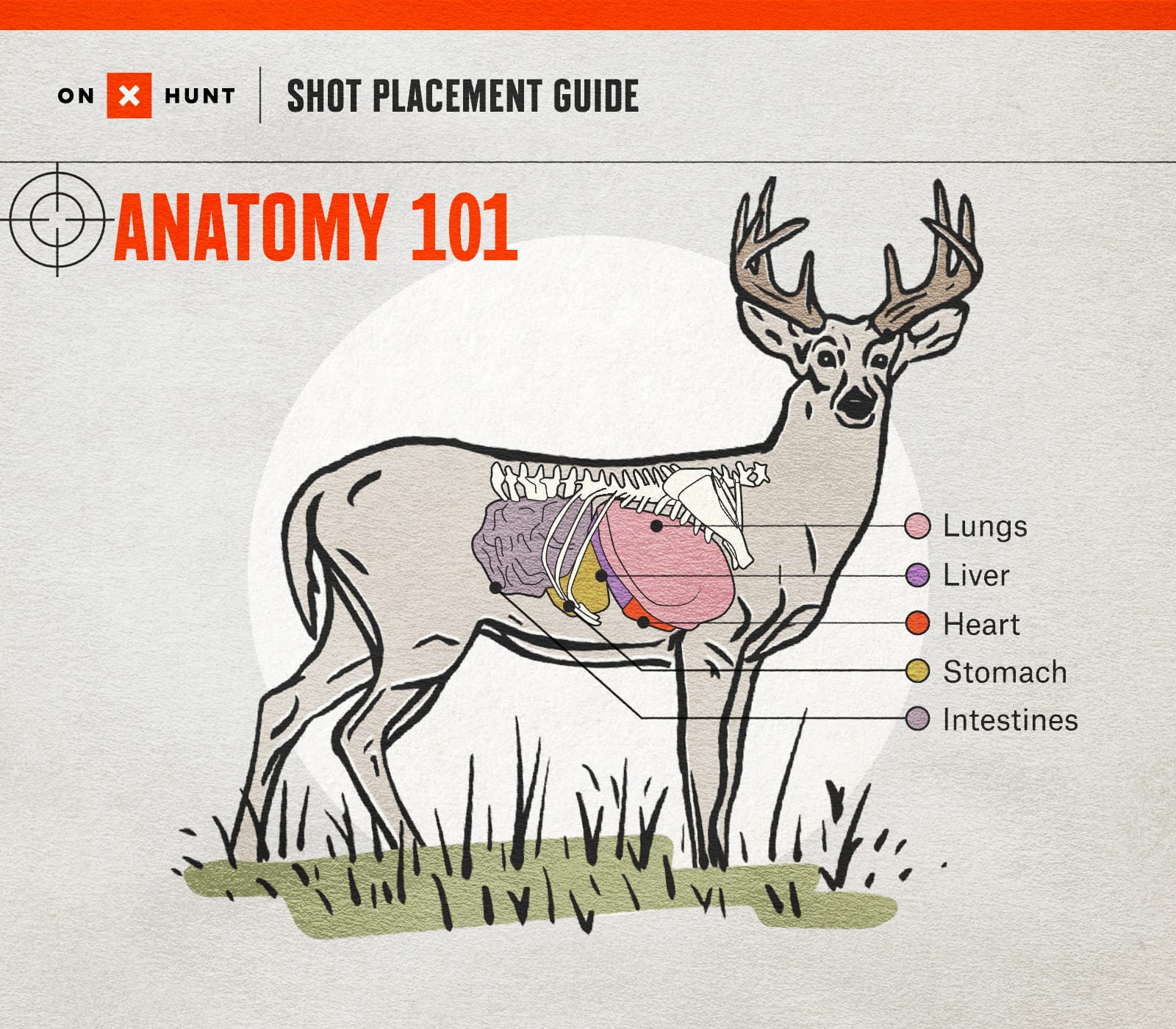

Deer Anatomy 101

There are many places where you can shoot a deer that are lethal, but to make the quickest kill possible, the shooter needs to understand the deer’s anatomy, particularly where its heart and lungs are inside its chest cavity.

Most hunters have been taught to shoot a deer just behind its front shoulder, no matter whether you’re shooting a bow or a firearm. However, a hunter does not need to shoot as far back as is often taught, especially when presented with a broadside shot. What appears to be the front shoulder, that rounded, muscled mass, does not contain as much bone as it might appear to, and thus gives us a clear path to its vitals.

As a quadruped, a deer’s anatomy is obviously different than a human’s, so we must account for and understand the additional bones and joints that make up its legs. The front shoulder of a deer has a triangular shoulder blade (scapula) that points forward and down, where it connects to the humerus at a point closer to the bottom of the neck than at the center of the shoulder. The humerus, which is similar to the forearm of a human, angles back to another joint we’d call the elbow. Coming out of the elbow are the radius and ulna, which are partially fused in most quadrupedal mammals, so what we would think of as the deer’s “knee” is actually its wrist.

With these bone and joint angles in play, that leaves a much larger unobstructed target area to aim at in order to hit vital organs, specifically the heart and lungs.

What Are Deer Vital Organs and Where Are They Located

A deer’s vital organs include the heart, lungs, liver, brain, and spine. It is the heart and lungs that should be targeted for the most ethical shots. Liver shots are lethal but should never be taken purposely. Head shots may result in a humane kill, but the target is small and should not be considered in most situations.

So where exactly are the deer’s heart and lungs located? A deer’s four-inch-tall heart is directly in line with the middle of its front leg, with the top of the heart sitting at the midpoint between its back and belly.

Of all the vital organs to hit, a heart shot will kill the deer the quickest because the animal bleeds out rapidly when either the atria (upper chambers) or the ventricles (lower chambers) are hit.

A deer’s four-inch-tall heart is directly in line with the middle of its front leg, with the top of the heart sitting at the midpoint between its back and belly.

A deer has a left lung and a right lung, with its heart between the two. The bulk of the two lungs is also set slightly behind the heart and behind its front shoulders. Given that the lungs fill most of the chest cavity, they give the hunter a much larger target than just the heart.

The liver is further back on a deer, located between its lungs and stomach and right behind the deer’s diaphragm. Its primary functions are to filter blood and make proteins that help blood clot. A liver shot is fatal but takes longer for the deer to expire (usually about two hours) because blood loss is slower from the liver than from a heart or lung shot. Liver shots produce dark red or maroon blood that also has a watery consistency.

One important fact to keep in mind when it comes to deer anatomy is that smaller deer can have vital organs half the size of a mature buck, so if you shoot at a young buck or doe, your margin of error can be reduced by 50 percent.

Where To Shoot a Deer

Now, let’s combine our knowledge of where a deer’s vital organs are with choosing the best shot placement for every common angle a hunter might encounter in the field.

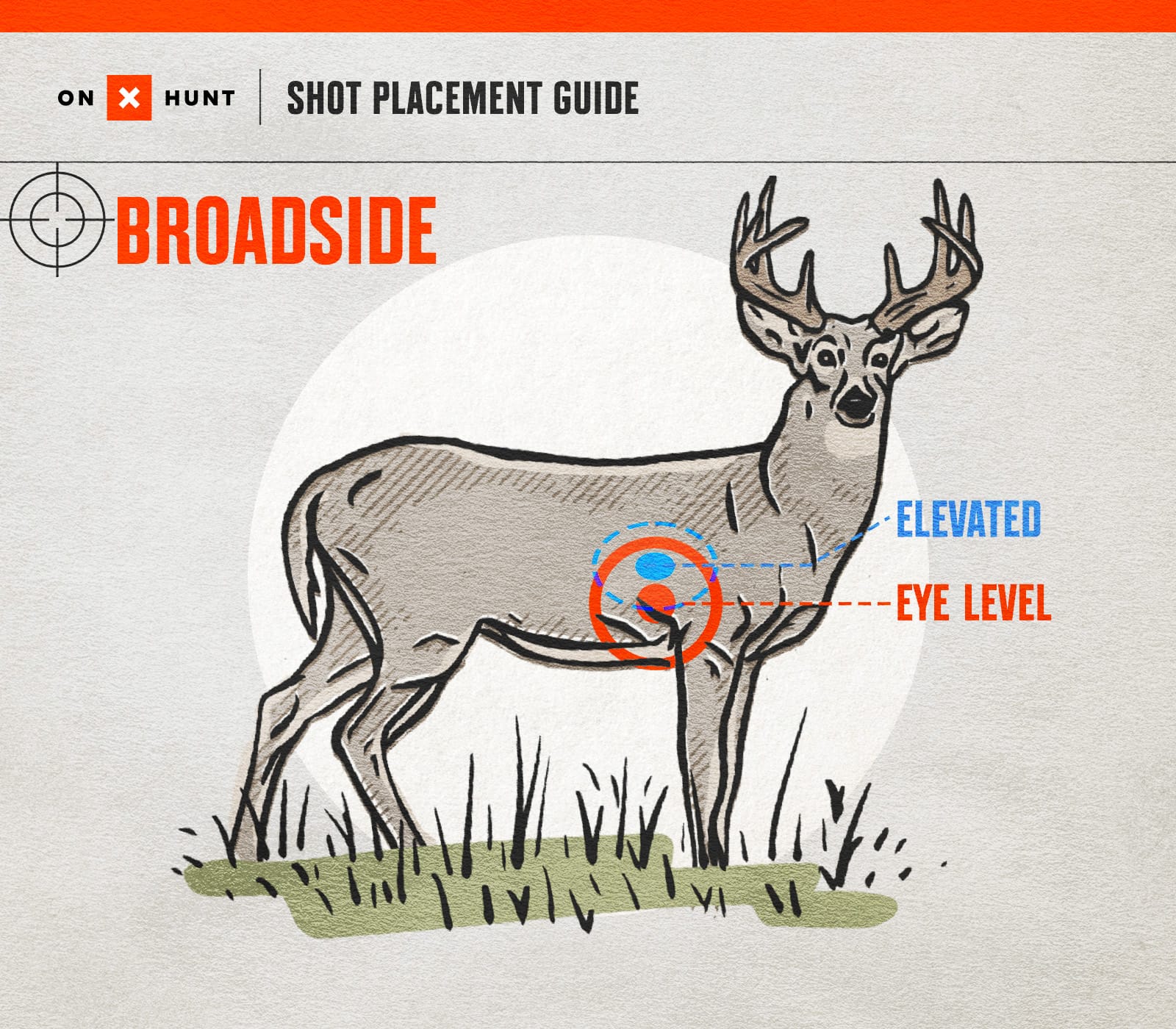

Broadside

Having a deer broadside at eye level is as good as it gets for a hunter. It gives you an unobstructed path to the heart and both lungs.

Having a deer broadside at eye level is as good as it gets for a hunter. It gives you an unobstructed path to the heart and both lungs. It’s possible to make a broadside shot that hits both lungs and clips the top of the heart.

The best broadside shot to take on a deer is to aim directly in line with the front leg and between the halfway and lower one-third mark between the bottom of the chest and the top of the back, keeping in mind a deer’s heart is situated at a 45-degree angle. Dropping your aiming point just below the middle line of the deer puts the shot in the meat of the heart (no pun intended).

The broadside shot also gives us the widest margin of error. If you miss an inch or so high, you get the top of the heart and two lungs. If you miss slightly to the left or right, you still hit two lungs. Missing further back and you’re in its liver territory.

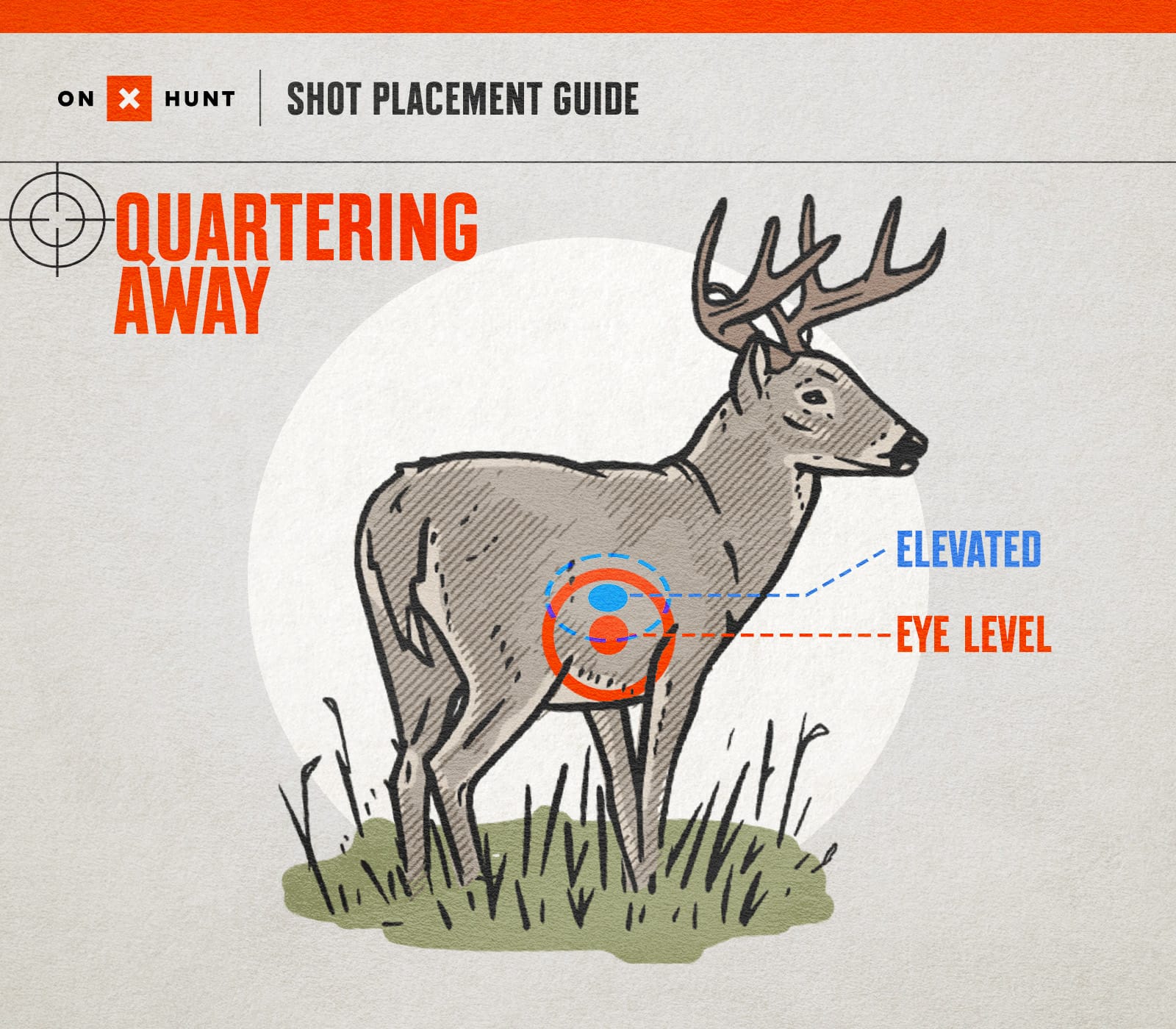

Quartering Away

Taking a shot when the deer is quartering away from you is the second-best shot you’ll have to broadside. Some hunters prefer this shot because the deer is less likely to detect you as you draw your bow or shoulder your firearm.

Taking a shot when the deer is quartering away from you is the second-best shot you’ll have to broadside. Some hunters prefer this shot in the field because the deer is less likely to detect you as you draw your bow or shoulder your firearm. When the deer is in this position, you have excellent access to its vitals on entry with a high likelihood of hitting at least one lung and/or the heart.

The key to making a quartering-away shot on a deer is aiming further back than its front shoulder. A good rule of thumb is to actually aim at the opposite-side shoulder, which is where you would want your arrow or bullet to exit.

For bowhunters, it’s critical that the arrow passes through the animal entirely so the entry wound isn’t plugged or you haven’t created an exit wound because it’s stopped by a bone. Without either or both wounds, there will be little-to-no blood trail, and if you only hit one lung, a deer can run quite a ways before expiring.

If you aim too far forward on a quartering-away shot, you risk missing the heart and lungs entirely and only damaging its front limb. Deer can live with only three limbs. However, if you aim a little too far back, you’ll still likely hit the liver and clip one lung, which is a kill shot but not as quick of one as a heart or double-lung shot.

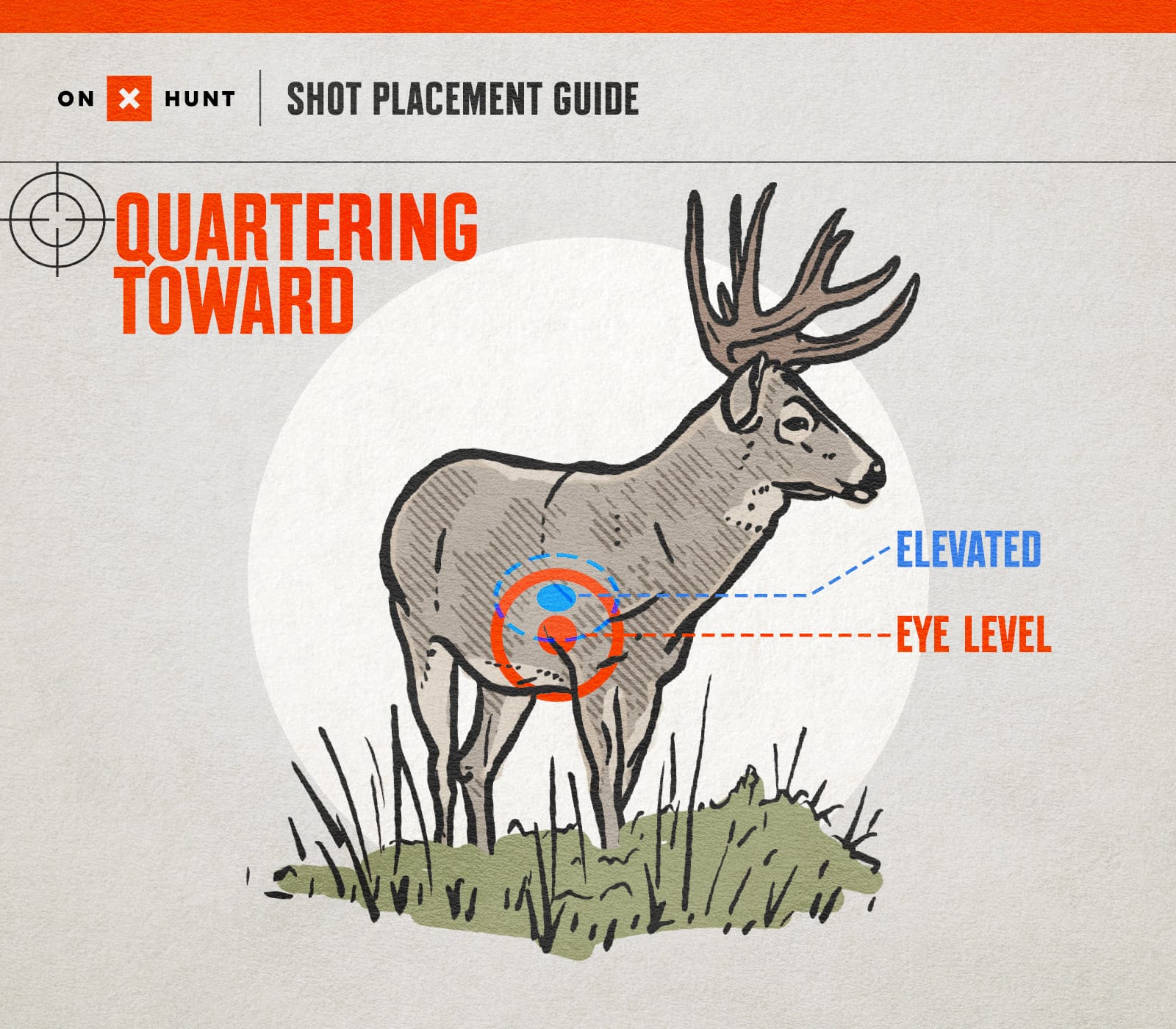

Quartering Toward

You should aim at the front side of the near shoulder, envisioning your shot exiting at the middle or back of the opposite ribcage.

The quartering-toward shot may look appealing in most situations, but this shot comes with greater risk than the two we’ve covered so far. The two major drawbacks to the quartering-toward shot are:

1. For bowhunters, you almost certainly need to shoot through the on-side scapula or humerus to avoid a gutshot. With lighter arrows or lower draw-weight bows, this is a considerable risk.

2. For rifle hunters, you are most certainly going to damage the front shoulder meat plus do substantial damage to the guts, risking spoiling additional meat.

But if this is the only shot with which you are presented, you should aim at the front side of the near shoulder, envisioning your shot exiting at the middle or back of the opposite ribcage. The height of the shot on the deer is the same at eye level as the broadside shot, just between the halfway and lower one-third of the body.

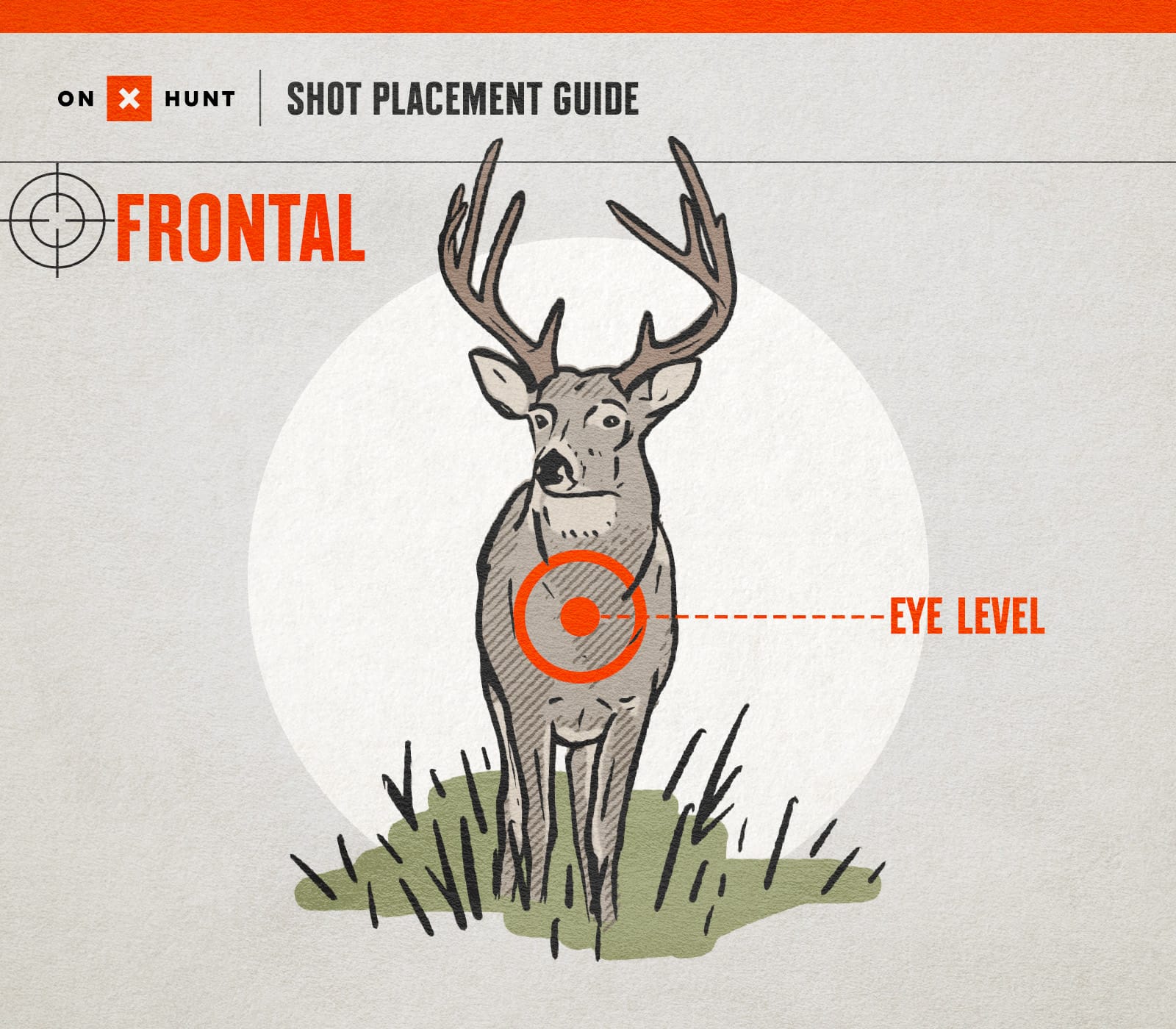

Frontal Shot

The most limiting factor is how small the target is from this angle. If you decide to take a frontal shot, don’t aim low.

Taking a frontal shot is ill-advised in most circumstances, and that’s true for bow and rifle hunters. The reason is the amount of bone and fatty tissue that impede arrows from reaching vitals while also preventing a pass-through shot, and a bullet will likely enter the guts and risk spoiling meat.

And that’s the best-case scenario with a frontal shot. The most limiting factor is how small the target is from this angle. Viewed from directly overhead, a deer’s ribcage width is only about 12 to 14 inches, and the heart as a target viewed from the front is less than three inches, given that a typical deer’s heart has a six- to seven-inch circumference.

If you decide to take a frontal shot, don’t aim low. The deer’s sternum will only block or deflect the brunt of the impact. Additionally, don’t aim to the left or right side of the chest cavity, imagining the heart is more to one side. Square the shot high and in the middle to avoid as much bone as possible and to give yourself the widest margin of error on a very small target area.

Angles and Shots To Avoid

There are many other angles and shots you will encounter in the field, but those not yet covered are not recommended. The two most common of these are the head/neck shot and the straight-away (also dubbed the “Texas heart shot”), in which the animal is standing, walking, or running away from you.

There is another shot, but one that is only available to those in treestands. That is the straight-down shot when it is directly underneath the hunter. This angle provides the smallest of targets, but some hunters will take it knowing the deer will be unaware of the hunter drawing on it or shouldering a gun.

If taking this shot, which is not an easy shot to make, you’ll have to know with certainty your arrow can penetrate the deer’s spine at least enough to sever the spinal cord (a bullet can), or if aiming slightly left or right of the spine to avoid it you’re still trying to get past its ribs. The best-case scenario at that point is to hit a single lung, which makes for a long day of tracking.

Uphill Vs. Downhill Shooting Angles

If you hunt in the hills or mountains, you’ll be faced with an uphill or downhill shot. It was once common to think that when shooting uphill, the bullet would hit higher than expected and that you should aim slightly lower than your target to compensate. On the other side of the coin, it was believed that a bullet would hit lower than expected in a downhill shot, requiring you to aim slightly higher to compensate. It’s since been proven that only half of that statement is true. Let us explain.

When you shoot level with the ground, gravity bears down on a bullet at a 90-degree angle, pulling it downward. This is called drop, and we compensate for it by sighting in our bows and rifles. When you shoot uphill or downhill, though, the angle reduces gravity’s pull, effectively flattening the bullet’s trajectory curve. So, the bullet doesn’t drop as much and hits higher than expected, whether shot uphill or downhill. This phenomenon becomes more noticeable at steeper angles and longer distances.

If your shot is at 100 yards or less, it’s not necessary to compensate for uphill vs downhill shooting angles because, with the majority of game animals, you will hit vitals if aiming dead-center where you want to hit. Many experts say that unless the slope is considerably steep, any shot out to 300 yards will be true enough to hit the target. Most modern-day rangefinders already compensate for angles and will give you the distance the shot will shoot like, but you can also find old-school calculations if you want to figure them out for yourself.

Lastly, be mindful that many of us overcompensate for angles. What we might think is a steep, 30-degree angle may really only be a 15-degree angle.

Be Mindful of String Jump

The other important factors to consider when taking any shot at a deer, and ones especially critical for bowhunters, are whether to shoot a deer when its head is up or down and whether or not to anticipate and compensate for “string jump.”

The deer head up vs. down debate centers on the animal’s ability to react to the sound the bow string makes when an arrow is released. It has been shown time and again that a deer with its head down can both react quicker and drop lower to the ground than a deer that has its head up.

This might seem counterintuitive since a deer with its head up appears alert, but consider that deer are prey animals and rely on smell, hearing, and sight to keep safe from predators. Among its senses, its ability to hear is stronger than its vision. Some claim that if a deer were human it would need glasses to see. So when the head is down, that deer is acutely aware of potential sounds that mean danger.

A deer with its head down can react quicker and drop lower to the ground than a deer that has its head up.

Related to knowing when to shoot is whether to compensate for “string jump.” As just discussed, deer are likely to respond in some way to hearing an arrow released from a bowhunter. With the speeds reached by modern bows, there is little time for a deer to react to shots taken at 20 yards or less. For longer shots, however, deer have more time to react.

MeatEater outlined the research of Dr. Grant Woods, and it demonstrated that a deer’s vitals can drop between two and six inches in response to an arrow shot from 30 yards (depending on the speed of the bow) and more than 10 inches in response to shots taken at 40 yards, which would cause most hunters to completely miss hitting the deer.

Some veteran hunters think it’s best to aim lower than they want to hit, betting on the animal dropping some amount. But veteran hunter Aaron Warbritton of The Hunting Public has told Outdoor Life that a deer’s reaction is “dynamic and different in every situation that you cannot predict what the deer is going to do.”

How To Shoot a Deer From a Treestand

Most bowhunters hunt from treestands, so understanding how height affects shot placement will make for more successful hunts. Treestand trajectory is a real thing, but it does not have to be a complicated one.

Generally speaking, the higher your treestand, the tougher all shots will be, and that’s due to how the deer’s backbone will shield its vitals, plus there is more foliage to deal with. This leaves bowhunters in high sets the smallest margins for error and chances of making a double-lung hit doubly hard.

The best shot placement adjustment to make from a treestand is to think only of the exit point for your shot, which will change dramatically depending on the height of your stand. The goal is for your arrow or bullet to travel through as much of the chest cavity as possible at any given angle. That likely means aiming further back on those quartering-away shots and aiming more in front of the near shoulder on quartering-toward shots.

The only way to master shots from a treestand, however, is to practice them regularly. Having a reliable rangefinder that has angle compensation will help you judge the correct shooting distance (hint: the straight line distance between a hunter in a treestand and the animal on the ground is not the actual shooting distance). Study, understand, and practice. To help you with all of those, we’ve created a free deer shot placement chart below.

Shooting Mastery

Like anything, practice makes perfect, especially for archery. It’s one thing to shoot at a home target or in a static shooting bay in a local range versus being able to replicate in-the-field conditions. But if you want to get closer to shooting mastery, here are a few tips to up your game:

- Join an archery club: Whether shooting indoors or outdoors, check to see if there is an archery club in your local area.

- 3D shooting courses: Some groups or non-profits may run a 3D course in your neck of the woods. For a nominal membership fee, you can access a course filled with life-sized targets of game animals.

- Check local high schools and universities: Many schools have archery programs and/or classes. Contact a school that has this type of program and ask if there are times when their targets are available for public use.

- Compete in a tournament: To truly mimic the pressure of making the shot when it counts, consider competing in a local or regional tournament.

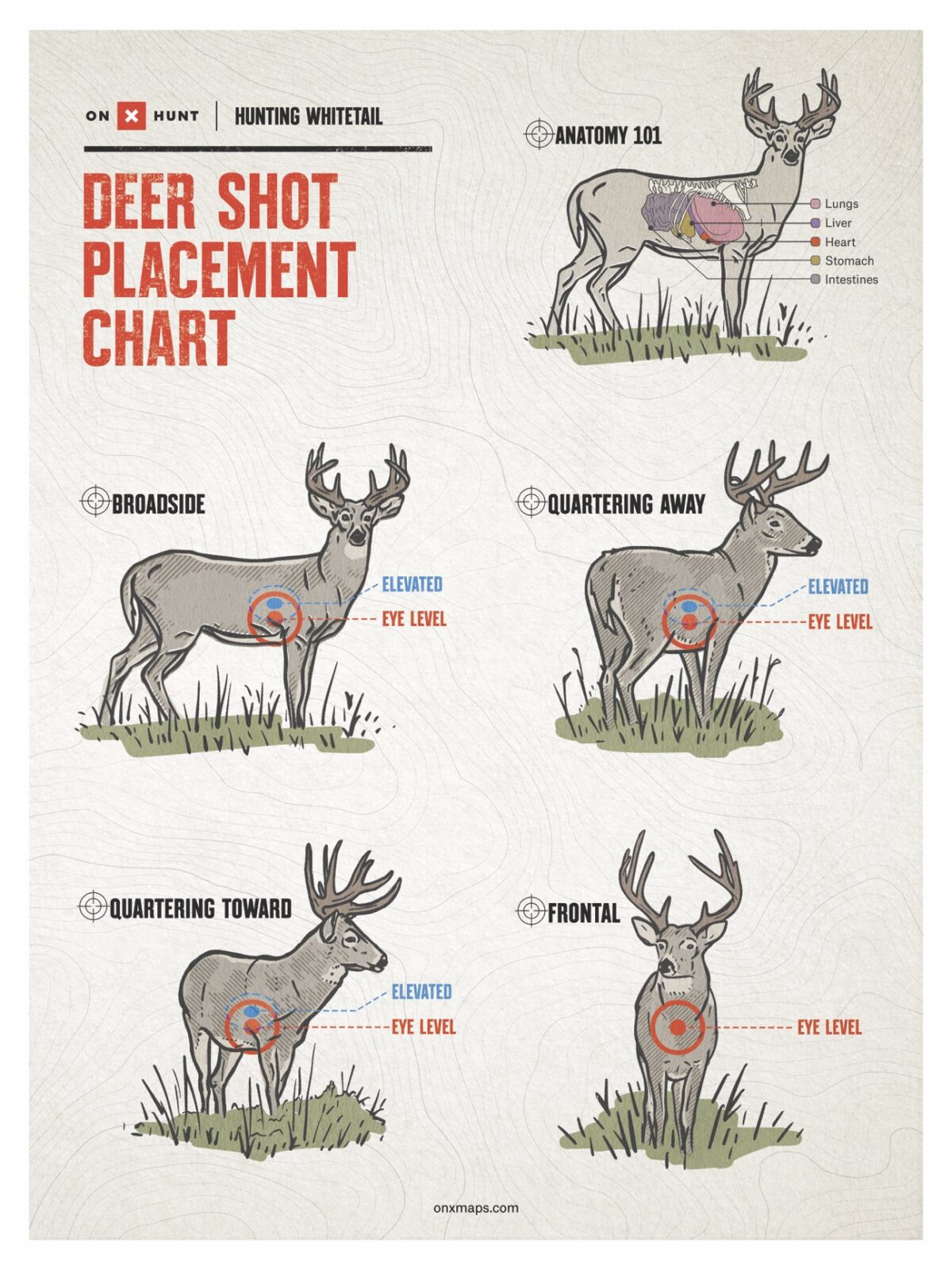

Free Deer Shot Placement Chart

Use this free deer shot placement chart to study the best shots from every angle. You can save it as a digital image on your phone, or it is also sized to print professionally at 18″x24″.

The #1 Deer Hunting App

Public/Private Landownership Maps, Optimal Wind on Waypoints, GPS Tracking, and More.

Frequently Asked Questions

All of the deer shot angles outlined above illustrate where to shoot a deer with a bow. However, the same shot placements will work when using a firearm or crossbow. Precise shot placement with a bow is important because the goal of every hunt should be making a quick, ethical harvest.

The best distance to shoot a deer with a bow depends on your maximum effective range with the bow you are using. You must consider the FPS (feet-per-second) speed at which your bow shoots, the grain weight of the broadhead (heavier broadheads generally provide better penetration), and the distance at which you can reliably hit your intended target. Many bowhunters are comfortable shooting deer up to 40 yards away.

Generally, no. Targeting the heart and lungs should be the goal with rifle hunting as it is for bowhunting. However, some rifle hunters will take head and neck shots on deer. A head or neck shot should never be considered when bowhunting.

A heart shot will kill a deer within minutes, likely not running more than 100 yards. With a double-lung shot, deer can live for 30 to 90 minutes. With a single lung or liver shot, a deer can live for four to six hours. A gut-shot deer can live for 8 to 12 hours, or longer, making recovery extremely difficult.

A deer shot in its vitals usually falls within 50 to 200 yards of where it was hit.

When tracking a deer you have shot, if you find blood droplets sprayed in clusters, it is most likely a heart shot. Blood that contains small bubbles indicates a lung shot. Arteries that have been severed produce bright red blood because that blood has been oxygenated. Severed veins produce dark red blood because that blood has been deoxygenated.

A deer that is hit in both lungs typically runs hard and fast, making long strides with its belly low to the ground.