Where are all the ducks?

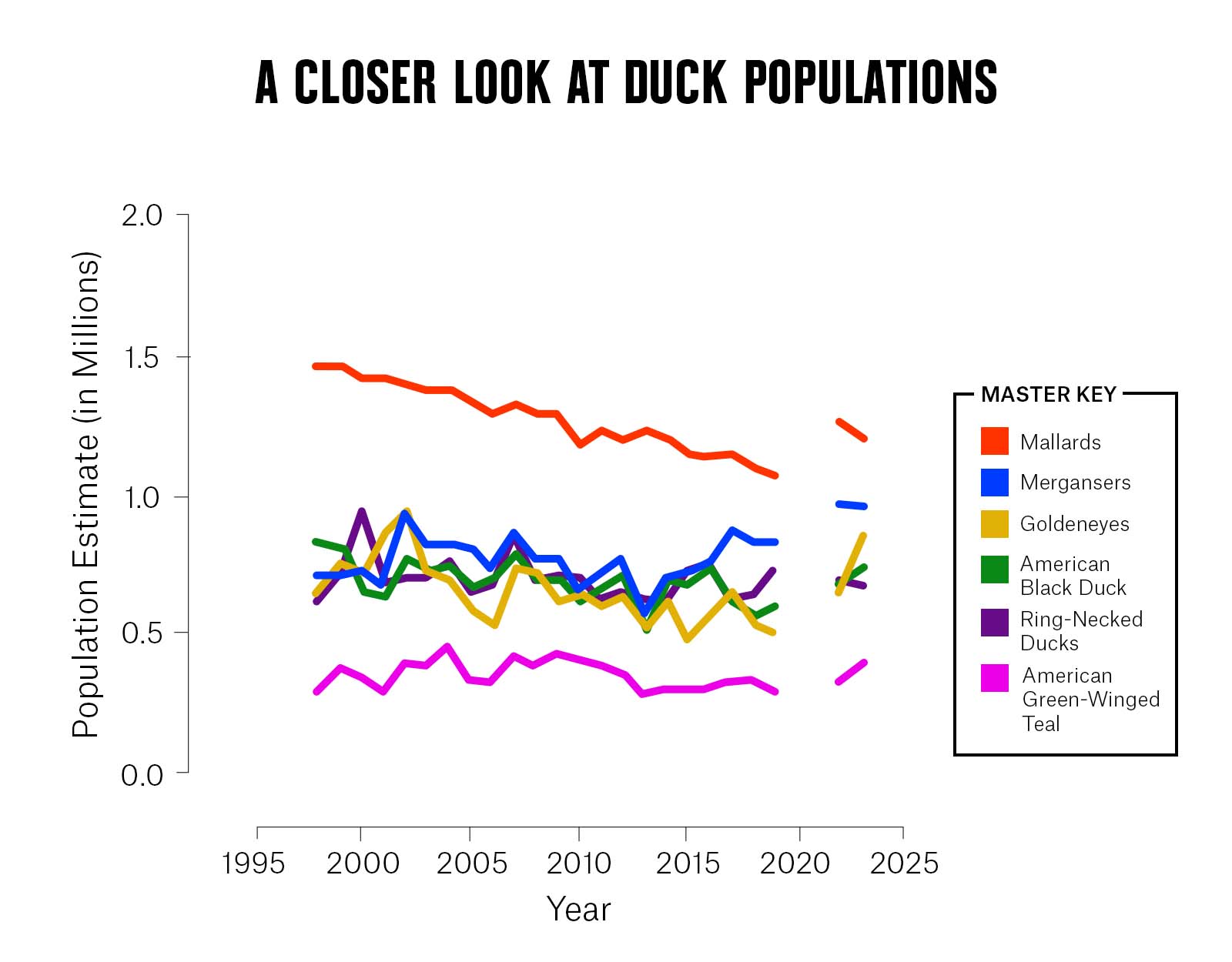

Duck hunting is changing. Fewer hunters are spending fewer days afield and harvesting fewer birds. Duck population estimates are down and waterfowl habitats are degrading. And, as waterfowl habitat degrades, ducks increasingly rely on the safe havens they know and trust—including private land and refuges with hunting restrictions.

These trends paint a pretty grim picture for waterfowlers, perhaps especially for public land duck hunters. So, as duck hunting changes, what role do we as hunters play?

We dig into this with the help of research from Cohen Wildlife Lab. Read on to learn about the interconnectedness of hunting pressure, duck habitat, and duck behavior—and what steps we can take today for better duck hunting tomorrow.

Duck Hunting Trends

Looking at duck hunting stats since 2019, duck harvests, active duck hunters, and days afield are declining. Duck population estimates are down 7% year-over-year, and since 2019, estimates are down about 17%.

In 2019, U.S. Fish and Wildlife estimated the duck population at 38.9M and reported about 873k hunters harvesting 9.72M ducks. Applying some rough math, that means there were about 44.6 living ducks and 11.1 duck harvests per hunter in 2019. Fast forward five years and duck population estimates stand at 32.3M ducks, with approximately 815k hunters harvesting 8.73M ducks. That’s roughly 39.6 living ducks and 10.7 duck harvests per hunter.

With fewer birds per hunter, how do we make the most of our season?

Duck Habitat: Shrinking Safe Havens

Before we dive into the research, it’s important to understand duck habitat, especially the rest areas birds use to avoid hunting pressure. Duck sanctuaries become increasingly important as waterfowl habitat loss continues. Wetlands are paramount to duck population success, but are experiencing steady declines. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service releases a Wetlands Status and Trends Report every 10 years. The latest report, released in 2024 and covering 2009 to 2019, indicates a net wetland loss of more than 50% since the previous study period.

While quality duck habitat may be shrinking, efforts are underway to help course-correct the trajectory, including those that support duck sanctuaries. Duck sanctuaries come in several shapes and sizes:

Wildlife Refuge Areas: Every waterfowl hunter must buy a Federal Duck Stamp, and dedicated waterfowlers understand these dollars go toward conserving migratory bird habitat, namely throughout the National Wildlife Refuge System. Wildlife Refuge Areas, also called sanctuaries or rest areas, offer ducks low-stress environments for basic needs such as feeding and mating.

Wildlife Refuge Areas are managed through a patchwork of regulations and local rules. It may not always seem like it, but hunting is allowed in over 70% of Wildlife Refuges. There’s also a subset of the National Wildlife Refuge System carved out as Waterfowl Production Areas, which are open to hunting unless otherwise specified.

Private Lands: Some private landowners and hunting clubs also create and manage waterfowl rest areas. Numerous organizations and government agencies manage programs that incentivize landowners to maintain wetlands and grasslands. A couple of program examples:

While quality duck habitat may be shrinking, efforts are underway to help course-correct the trajectory, including those that support duck sanctuaries.

Several universities and labs are also researching the nexus between duck habitat, hunting pressure, and duck behavior to understand how to improve duck numbers, and thereby, duck hunting.

Case Study: How Hunting Pressure Affects Duck Behavior

To get a better handle on the current landscape, we connected with the Cohen Wildlife Lab, led by Dr. Bradley Cohen. The team there focuses on habitat-species interactions, predator-prey dynamics, and wildlife ecology and management.

The Study: Following 900 Mallards Over Five Years

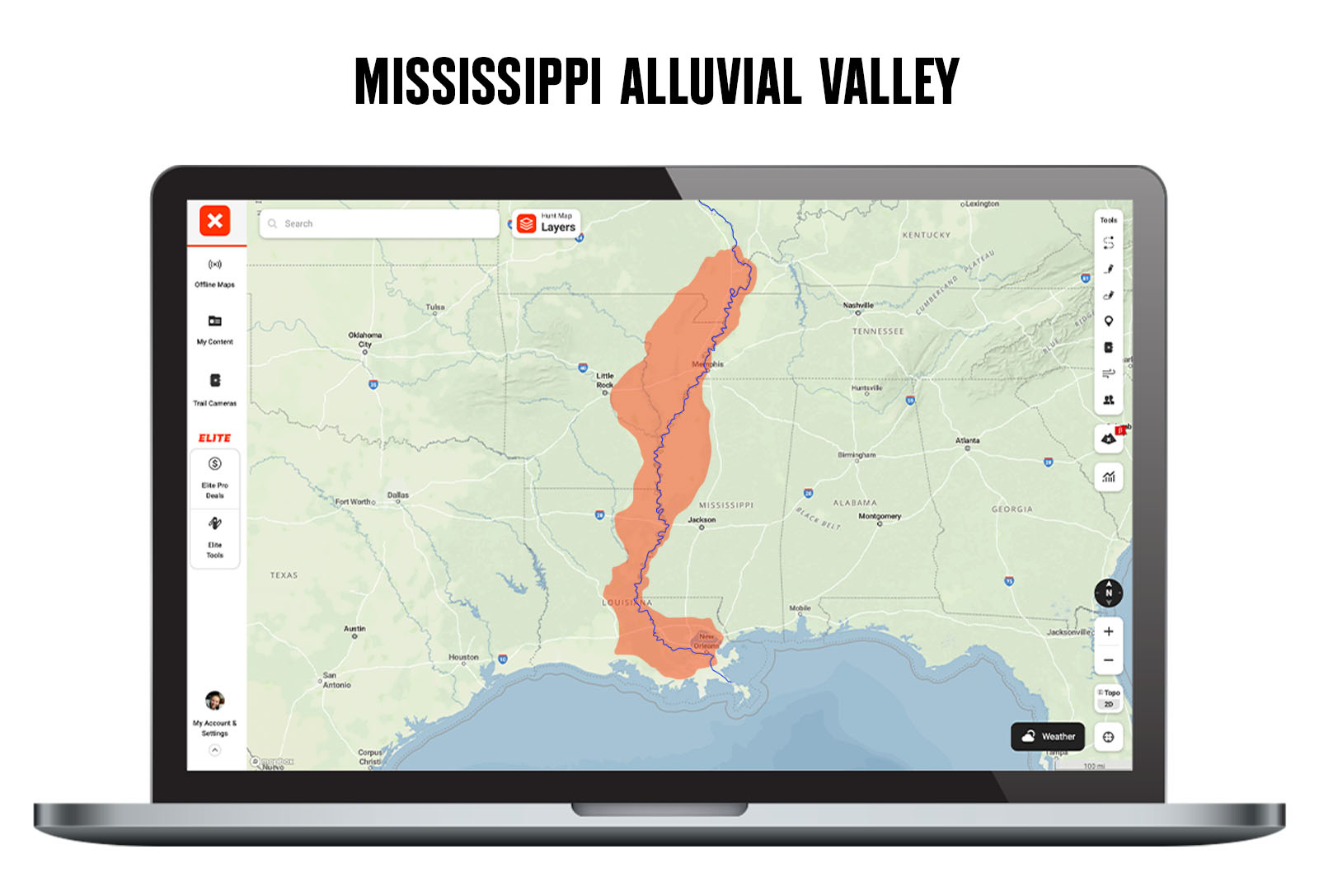

Over the past five years, Dr. Cohen and his students, Cory Highway, Nicholas Masto, Abigail Blake-Bradshaw, and Lydia Holmes have partnered with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and other collaborators to investigate the ecology of wintering mallards in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. Their research is based in western Tennessee where they capture mallards every fall and fit them with GPS transmitters to track their every move during the winter.

The team followed nearly 900 mallards for half a decade to glean valuable information on mallard behavior, including how they use food resources and avoid predation. Throughout the study, the researchers went out on the landscape and measured variables that may impact mallard movements and habitat use, including food availability and hunter pressure.

The Study Area: A Changing Landscape

The Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley (LMAV) is the nation’s largest floodplain, running from southern Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico, and comprises 24 million acres across Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. The LMAV is one of the most continentally significant wintering and migration areas for several waterfowl species including mallards, wood ducks, gadwall, green-winged teal, American wigeon, and hooded mergansers.

The LMAV creates a bottleneck, funneling birds from across the northern prairies of Canada and the United States into one fairly small region. Hunters caught on quickly to this concentration of birds and the Mississippi Flyway has been a historic landmark for centuries of waterfowl hunters.

Like a lot of waterfowl habitat, the LMAV’s landscape has changed considerably over time. The LMAV was traditionally dominated by millions of acres of bottomland hardwood forests where wintering waterfowl could feed on acorns and invertebrates and hide from hunting pressure, which was generally more sporadic due to perpetually changing water levels and difficult access.

Now, the LMAV is an agriculturally-dominated landscape with more controlled water levels. This habitat restructuring has confined both hunters and ducks to smaller areas of the landscape and increased the predation risk that waterfowl face during the winter. Waterfowl have adapted to this agriculturally dominated landscape and the intense hunting pressure found here.

Habitat restructuring has confined both hunters and ducks to smaller areas of the landscape and increased the predation risk that waterfowl face during the winter.

Duck Behavior: How Are Ducks Using Refuges?

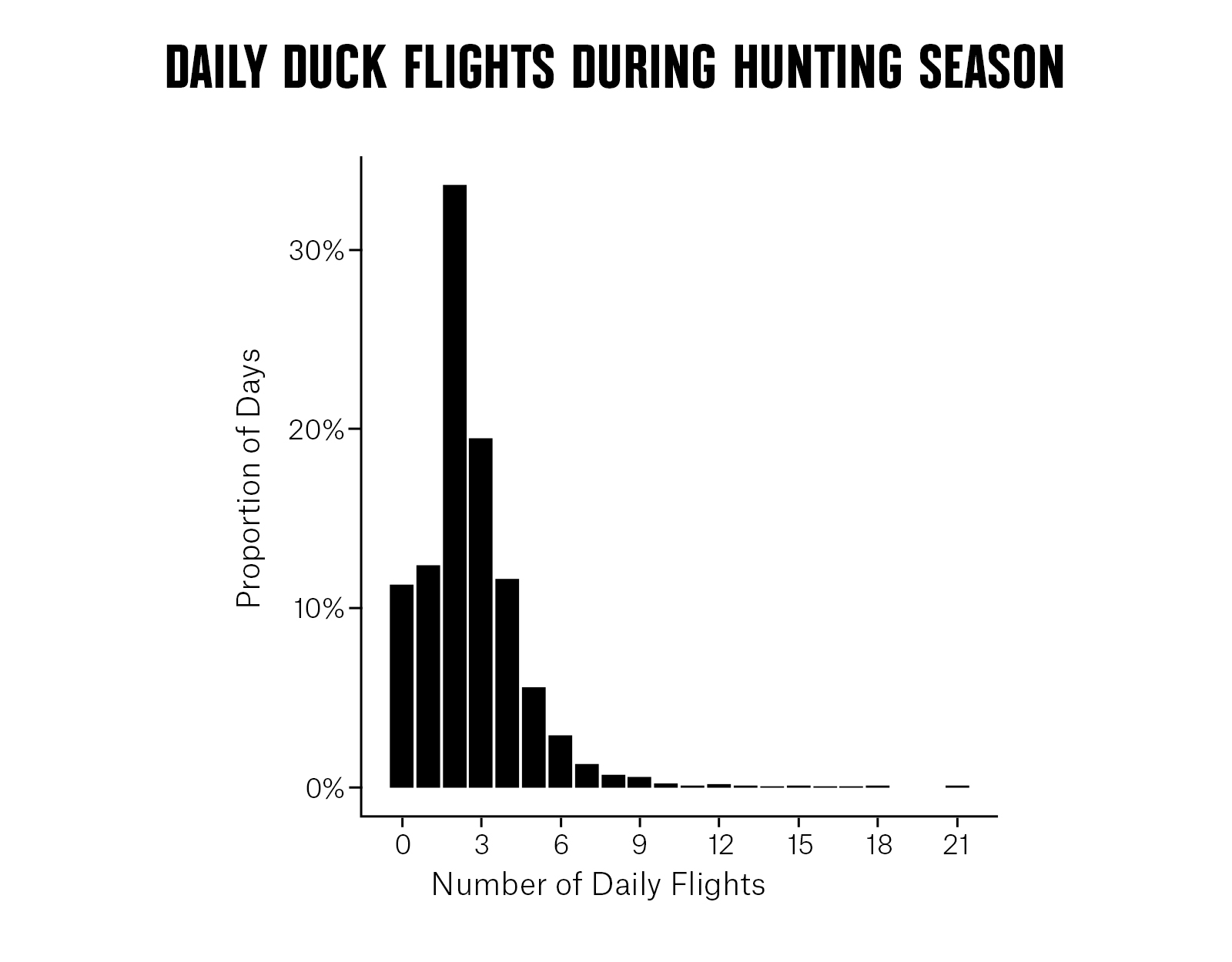

The Cohen Lab’s GPS-marked mallards find ways to survive the hunting season primarily by reducing their flight distance and frequency. Throughout the study, the Cohen Lab noticed that most of their mallards only made two or fewer flights per day. When they did fly, mallards were generally moving in the morning and at dusk, with twice as many flights occurring in the evenings as in the mornings. This is likely due to the fact that hunting ends a half hour earlier in the evening, which allows ducks to explore the landscape looking for a place to forage overnight.

Most mallards made two or fewer flights per day. When they did fly, they generally moved in the morning and at dusk, with twice as many flights occurring in the evenings as in the mornings.

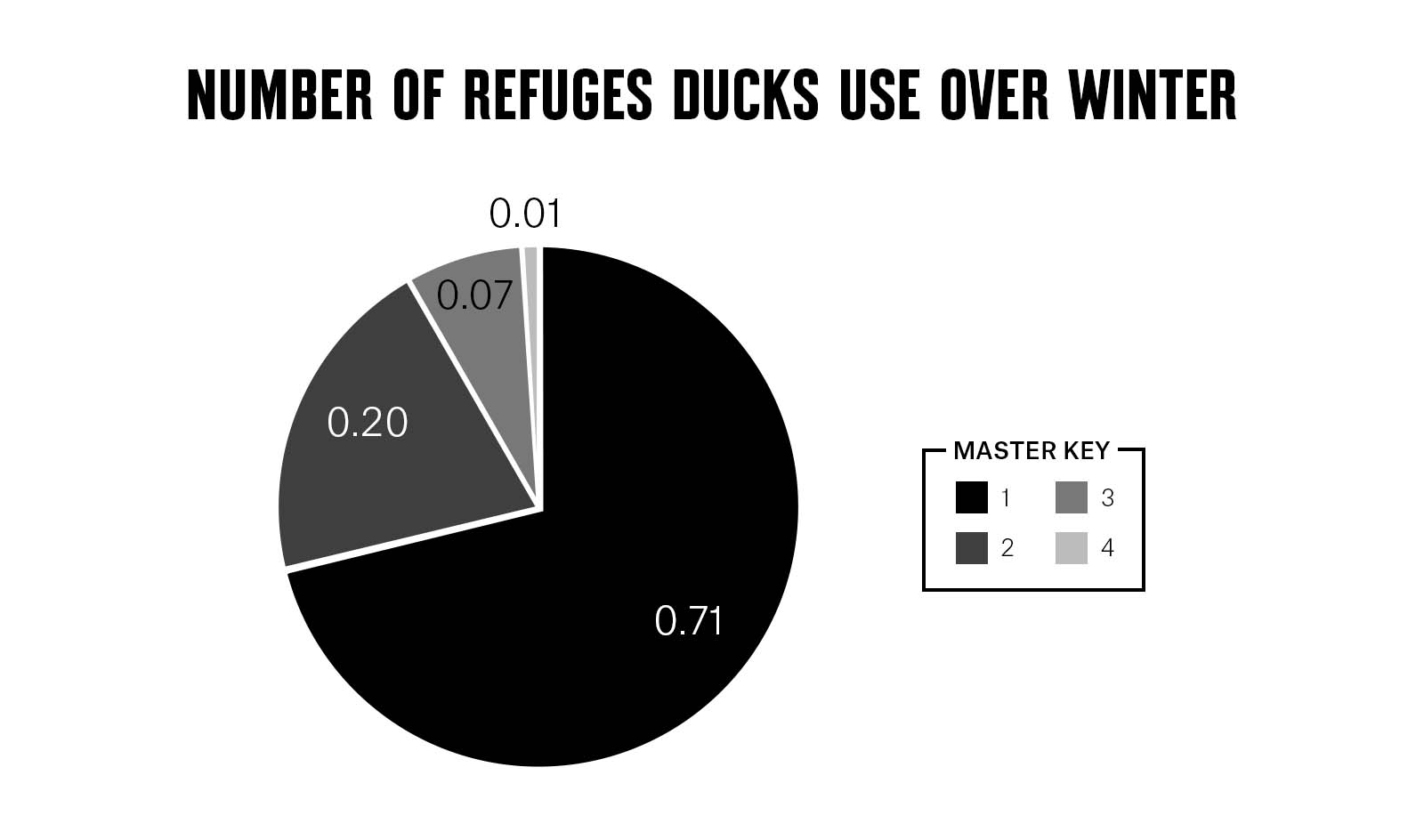

In the mornings, mallards generally returned to the refuge they were at the day before and stayed on that refuge throughout the day. In fact, 71% of GPS-marked mallards only used one refuge the entire winter with an additional 20% using two refuges. If refuges were over 19 miles apart, there was virtually no chance that a mallard would “hop” between the refuges. When mallards did leave a refuge, they generally did not fly far: 85% of off-refuge flights occurred within 2.5 miles of the refuge, which limits the availability of ducks to be harvested by hunters who are not immediately around a refuge.

Once the mallards found a safe area, they tended to stay put. This chart breaks down the number of refuges ducks used over winter. More than 90% of birds used two or fewer refuges.

So, the logical questions are:

- How do we get ducks off refuges and increase hunter opportunity?

- If we push ducks off refuges, how does it affect duck behavior?

Field Experiments: What Do Ducks Do When We Add Pressure?

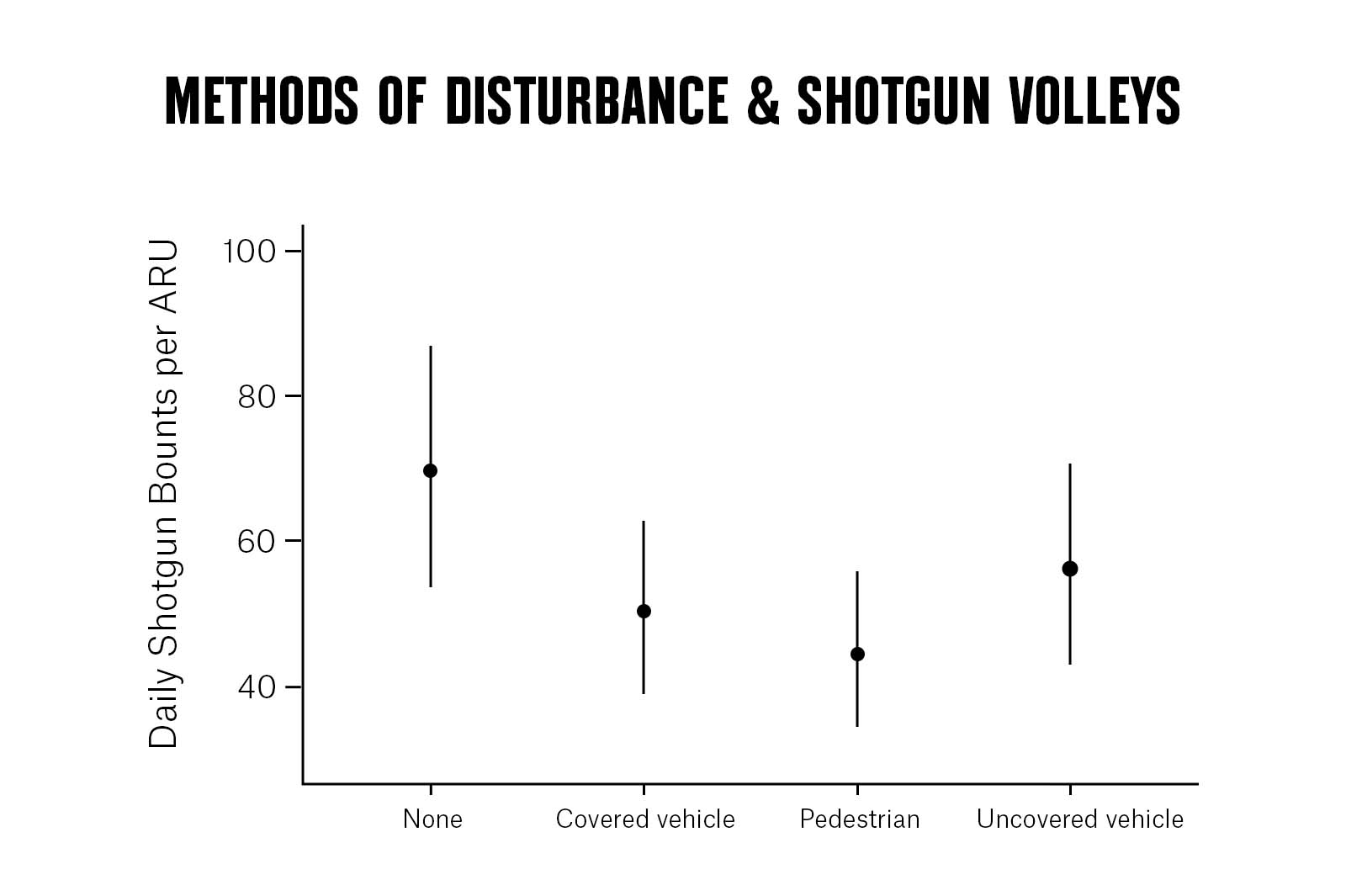

The Cohen Lab ran field experiments to purposely disturb ducks in sanctuaries, using a pick-up truck, pedestrians, ATVs, and boats in an effort to push ducks onto hunted lands. After 223 disturbances, the team concluded that although ducks increased their movement when disturbed, they immediately settled down after the disturbance and then flew less frequently for several days after the disturbance. Additionally, the ducks did not leave the refuge—in fact, their refuge use increased. So disturbing ducks just scared them still; they hunkered down instead of flying somewhere else.

Although ducks increased their movement when disturbed, they immediately settled down after the disturbance and then flew less frequently for several days after the disturbance.

While the researchers were tracking how ducks handled this disturbance, they were also monitoring how sanctuary disturbance affected hunter opportunity. The researchers deployed Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs) to listen to and count shotgun volleys around the refuges.

On days when sanctuaries were disturbed, shotgun volleys decreased by 32%, indicating that when those ducks were hunkering down after disturbance, they weren’t available to hunters, and hunting success decreased.

The field experiment strongly suggests that both waterfowl and waterfowl hunters need undisturbed sanctuary areas, introducing a new question: How do we distribute birds across the landscape and increase hunter opportunity?

Putting Insights To Use: Balancing Conservation and Hunting

Researchers in the Cohen Lab now aim their investigation toward increasing hunter opportunities by expanding the distribution of wintering mallards across the landscape. The strong preference for safe areas (i.e., sanctuaries), coupled with small movements, results in little movement of mallards up and down the river corridors of West Tennessee.

Because most refuges in West Tennessee are farther than 2.5 miles apart, most mallards in the area do not use more than one refuge. The lack of connectivity between refuges results in mallards learning the fine-scale details of their limited home range so they can better avoid hunters.

Interestingly, mallards that used more than one refuge had lower survival. In other words, mallards that traded between multiple refuges and used more of West Tennessee’s river corridors were more likely to be harvested. It is possible that having small areas of undisturbed land (i.e., rest areas) along the river corridors may provide the habitat patches necessary to connect the West Tennessee wetlands and redistribute waterfowl across the entirety.

The lack of connectivity between refuges results in mallards learning the fine-scale details of their limited home range so they can better avoid hunters.

What’s Next? Supporting a Network of Rest Areas

The Cohen Lab is collaborating with conservation partners to establish undisturbed rest areas along the Mississippi, Obion, and Forked Deer Rivers of western Tennessee to serve as “stepping stones” to safe habitat. By adding rest areas, researchers believe waterfowl movements and range sizes will increase and subsequently spread duck distributions across the river bottoms.

Increased duck distributions will improve resource utilization and may slow the depletion of resources adjacent to established sanctuaries. Rest areas in close proximity may also discourage waterfowl from setting up a single home base; therefore, they won’t be as familiar with their surroundings and may be more susceptible to harvest. In other words, the team hopes that connecting safe areas will increase waterfowl use of wetlands across western Tennessee and improve hunting opportunities.

The team hopes that connecting safe areas will increase waterfowl use of wetlands and improve hunting opportunities.

How Can Waterfowlers Help Prevent Stale Ducks?

While this research is rooted in western Tennessee, all hunters can leverage insights to support their success afield. The most important takeaway from Cohen Lab’s research is that ducks are highly perceptive to hunting pressure and will change their habits to survive if they feel constant patterns of pressure.

Figuring out how to reduce your impact on the birds you hunt may markedly improve your hunting success. For example, frequently switching locations and resting hunting spots will allow waterfowl to filter into the area without the constant threat of harvest. Being unpredictable in your timing may create the illusion that the predation risk is low in an area.

Public Land Hunting Tips

For public land hunters, it may be harder to “rest” a hunting spot when other hunters also use the area. In this case, and with most any public land hunting, scouting can be the most important determination for a successful hunt. However, scouting quietly by walking or paddling instead of driving and boating as well as reducing your disturbance by observing and listening from a distance may keep birds in the area longer.

One last key to keep in mind is to watch the weather and hunt when birds are most likely to be active. The Cohen Lab explored which factors were most likely to indicate increased movement from GPS-marked mallards. The figure below shows how the number of daily flights made by wintering mallards changes based on several environmental conditions. The key takeaway? Mallards were more likely to fly during hunting hours before and during storm events when barometric pressure was dropping, wind increased, and precipitation was occurring.

Not everyone can pick their days in the swamp, but look for this “ducky weather” on the forecast the next time you are thinking about chasing waterfowl.

Chart 1: Daily flights experience a sharp decrease after opening day and then rebound steadily. Upwards of 75% of ducks were found on a refuge during opening day. But they learn quickly: Harvest opportunities declined by 50% after opening day, indicating waterfowl adapt quickly to hunting pressure by finding safe-havens.

Chart 2: Lower barometric pressure correlates to increased duck flights during open season hunting hours.

Chart 3: Cooler temperatures correlate to increased duck flights during open season hunting hours.

Chart 4: Higher wind speeds correlate to increased duck flights during open season hunting hours.

Chart 5: Higher river levels correlate with fewer duck flights during open season hunting hours.

Chart 6: Increased precipitation correlates with increased duck flights, especially during open season hunting hours.

FInd More Ducky Areas With OnX

Land ownership info, hundreds of map layers, and advanced terrain analysis tools.