A new series dedicated to sharing the latest science and research so we may all better understand wildlife and the challenges they face.

By Patrick Wightman

Abstract

Between 2019 and 2023, a series of five turkey gobbling-related papers were published in a variety of scientific journals. Each paper documented results from studies led by Dr. Mike Chamberlain (University of Georgia) and Dr. Bret Collier (Louisiana State University). These studies were funded by the South Carolina and Georgia Department of Natural Resources and conducted by myself and numerous graduate students associated with each project.

These papers were the first to tackle gobbling-related questions with the use of autonomous recording units (ARUs) instead of traditional roadside surveys, along with GPS tracking data on turkeys instead of very-high-frequency (VHF) telemetry. In the past, roadside surveys and VHF were limited to the amount of time in which data could be collected. ARUs and GPS trackers, by contrast, could be placed on the landscape to collect detailed data for longer periods of time.

Specifically, these technological advancements allowed us to collect gobbling activity from March 1 through the end of June, each day, an hour before sunrise until five hours after. For one research project, we even collected gobbling activity from an hour before sunrise until an hour after sunset. The GPS units allowed us to collect hourly GPS locations from turkeys during the day and a nightly roost location for about a year after capture.

Over the course of the five studies, we were able to detail what gobbling chronology looks like during the reproductive season, discuss how hunting regimes, harvest, and variation in daily weather influence gobbling, along with how female reproductive timing compares to gobbling activity.

The Studies, Methods, and Data

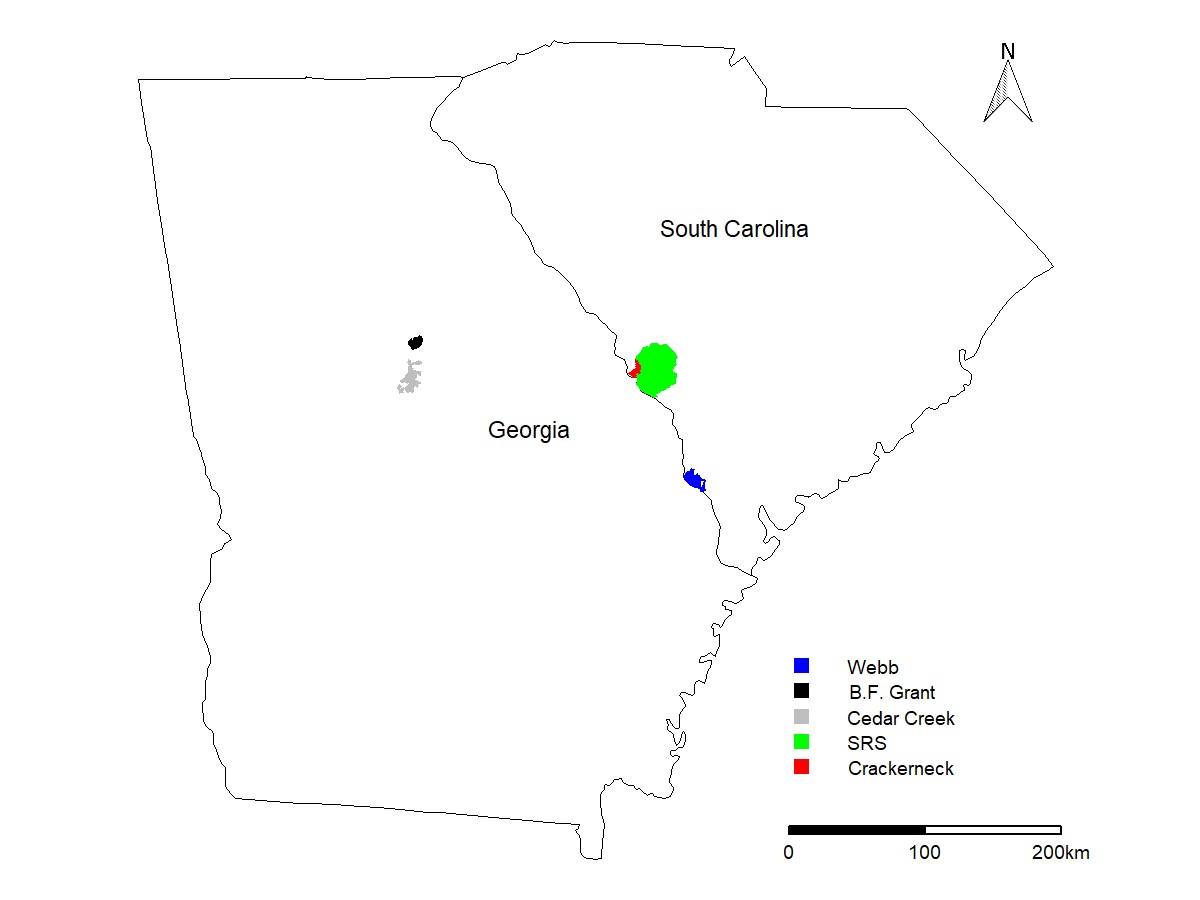

The first study published in 2019 came from a multi-year project monitoring and recording gobbling activity of the Eastern wild turkey on three different sites in South Carolina. The three sites represented different levels of turkey hunting pressure, with one being open to public hunting every day of the season, another being open to the public only on Fridays and Saturdays during the season, and the last location was closed to hunting altogether. Over two years, we collected 68,426 gobbles, and from that data, we determined what gobbling activity (aka. chronology) looked like within a day and then during the reproductive season. Given that gobbling activity is a key determinant of hunter satisfaction, and gobbling chronology is often used by state agencies to inform regulatory processes, such as season dates, we wanted to determine how hunting influenced gobbling and how it coincided with the current season.

In the second study published in 2019, Eastern wild turkey gobbling activity was studied as it related to male movements and female nesting phenology, which is the study of cyclic and seasonal natural phenomena in plants and animals. Male turkeys gobble to attract females for reproduction and to establish dominance amongst other males, and we know that males begin gobbling in the spring as daylight increases and testosterone rises. Historically, researchers noted that peaks exist in gobbling activity, but the goal of this paper was to examine the relationship between reproductive phenology (aka. when the hen was laying or incubating a nest) to potential increases/peaks in gobbling activity. In the past, researchers believed that gobbling would peak with incubation. We wanted to test this hypothesis.

We used GPS data from 70 female turkeys and 29 male turkeys in the Webb WMA complex in South Carolina to determine the mean incubation dates and the relationship to male gobbling. Furthermore, we wanted to see if there was a relationship between daily distance traveled in males and gobbling activity.

In the third study published in 2020, we took what we knew from the previous papers–that hunting and reproduction activity influence gobbling–but now we wanted to better understand how the removal of male turkeys and the reproductive timing of females simultaneously might influence gobbling. This study used data from two WMAs in the Piedmont of Georgia, lying between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Upper Coastal Plain, we collected 13,177 gobbles during 2017 and 2018.

In the fourth paper, published in 2022, we wanted to examine the influence of weather on gobbling activity for male Eastern turkeys.

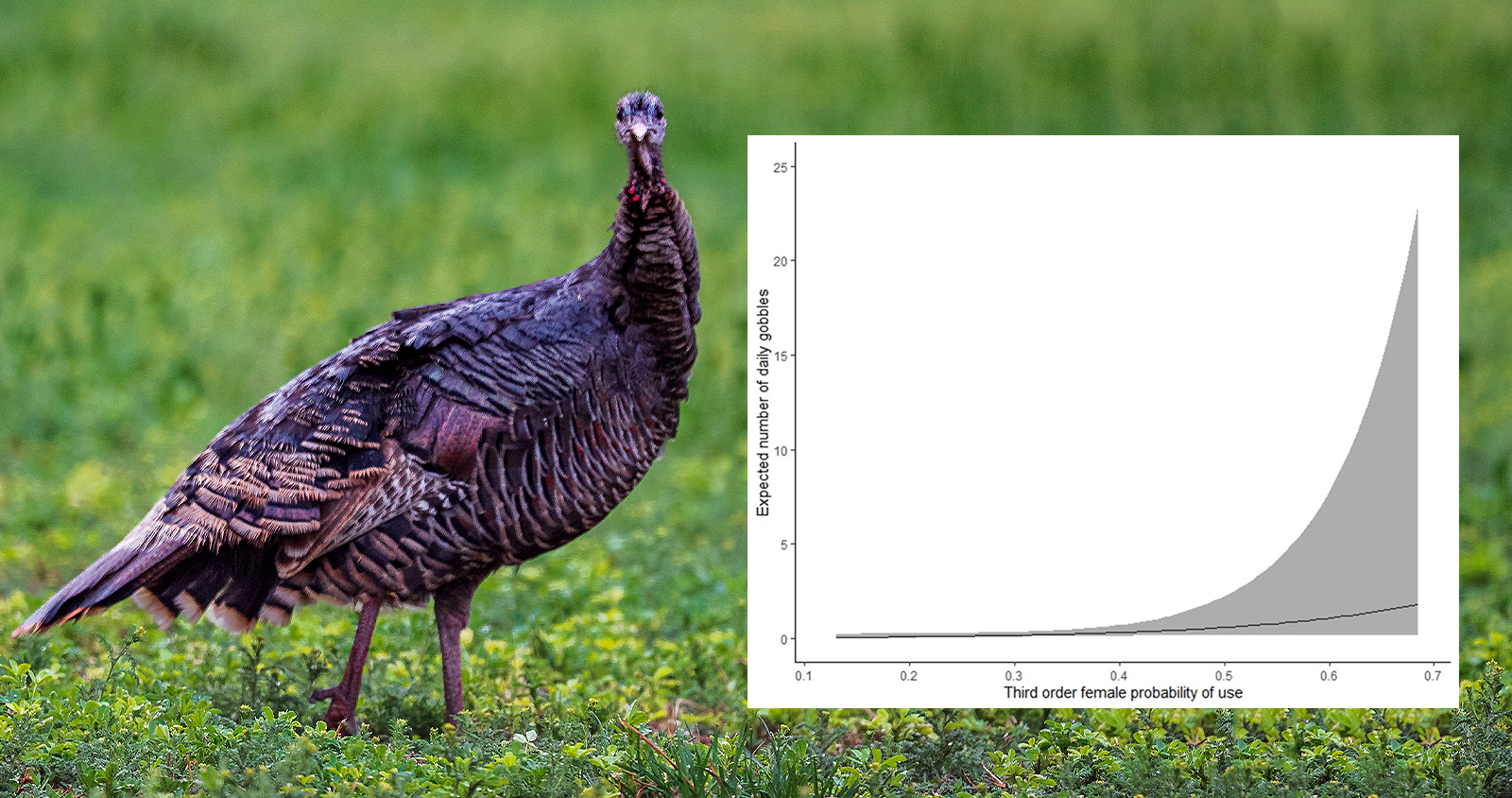

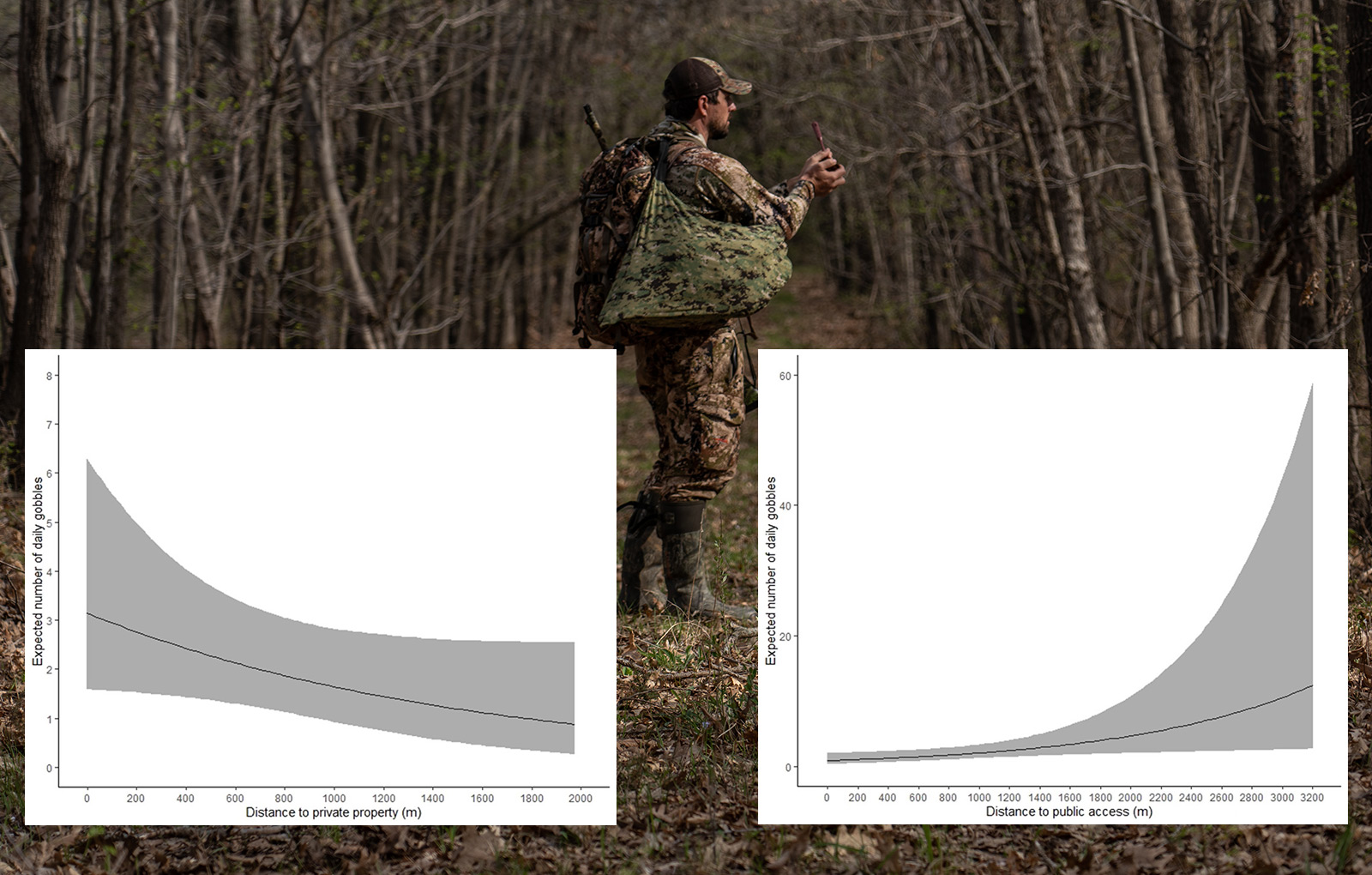

In the fifth and final paper, which we published in 2023, we studied landscape characteristics and predation risk and how they influence gobbling activity of the Eastern wild turkey. We had already established that gobbling activity varied highly on hunted sites. Now we wanted to try to predict where on the landscape we would see higher gobbling activity as the hunting season progresses. To do that we tested three different hypotheses: one being that turkeys will use different areas of the landscape as the season progresses and this will relate to increased gobbling activity. The second is that turkeys will gobble more if there are fewer predators, both human and natural associated with an area. This makes sense as male turkeys must balance gobbling to attract mates with the potential negative of also attracting predators. Lastly, we hypothesized that turkeys will gobble more in certain land cover or vegetation types.

For this study, we used GPS data from 81 female turkeys and 30 male turkeys to predict turkey use as the season progressed. Then we used GPS data from 36 coyotes to predict risk from a natural predator and distance metrics from public access points, private property, and roads to predict human risks.

We used the recording devices to count daily gobbling activity at numerous locations across our study sites, illustrated in the lightbulb map below. The larger the bulb, the more gobbling activity. We noted how turkeys gobbled in different locations as the hunting season progressed particularly that certain areas on the landscape continued to have gobbling activity while others did not. The objective of the study was to determine which of the three hypotheses described above had the greatest impact on predicting these areas of increased gobbling activity.

A Story From the Field

While having “ears” in the trees during turkey season as one may expect we have listened to many interactions with hunters and turkeys over the years. Some interactions result in cheering and yelling with joy as hunters embrace the success of harvesting a turkey. One morning we listened to a hunter shoot and were not left wondering if he was successful as his phone call to report his harvest via telecheck was recorded. However, not all interactions result in a harvest, and sounds of frustration can be heard through cussing, bickering, and yelling. On one particular morning, we listened to a hunter calling in a turkey and could tell the bird was getting close as we could hear drumming and the bird walking in the leaves. As we sat in suspense listening for a shot all we heard was a cell phone ringing and the yells of frustration from the hunter.

The Results

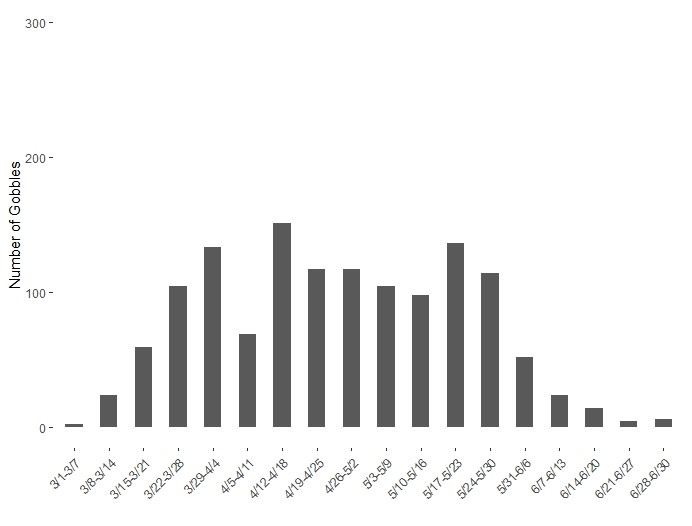

In the first study, we found >70% of gobbles occurred between 30 minutes prior to and 60 minutes after sunrise. We found that gobbling activity was influenced by hunting regimes, as the average gobbles per unit were 27% greater on the non-hunted site compared to the limited site that was open two days a week and 45% greater compared to the site that was hunted six days a week. This theme of gobbling being more varied on sites with more hunting pressure was present across all our studies. Gobbling chronology from the non-hunted site can be seen in the figure below.

In the second study, we found, contrary to historical literature, no relationship between peaks in gobbling and the onset of incubation. We did, however, observe a relationship of gobbling beginning to increase 37 days before nest incubation, which is likely when females started to become receptive to breeding and males began competing for breeding opportunities. Secondly, we observed a peak in gobbling with a lag of 10 days before the mean incubation date (April 23, accounting for both years of the study). This coincides with the onset of laying in females. Females lay, on average, 10 eggs, and they will lay one egg each day before beginning to incubate the nest. We failed to find a relationship between male daily distance traveled and gobbling activity.

In the third study, we found that gobbling activity increased with the onset of reproduction, but noted that the onset of hunting and removal of males had a larger impact, decreasing gobbling activity. Particularly for this population, we noticed the biggest decline in gobbling once four males were removed per ~2,000 acres.

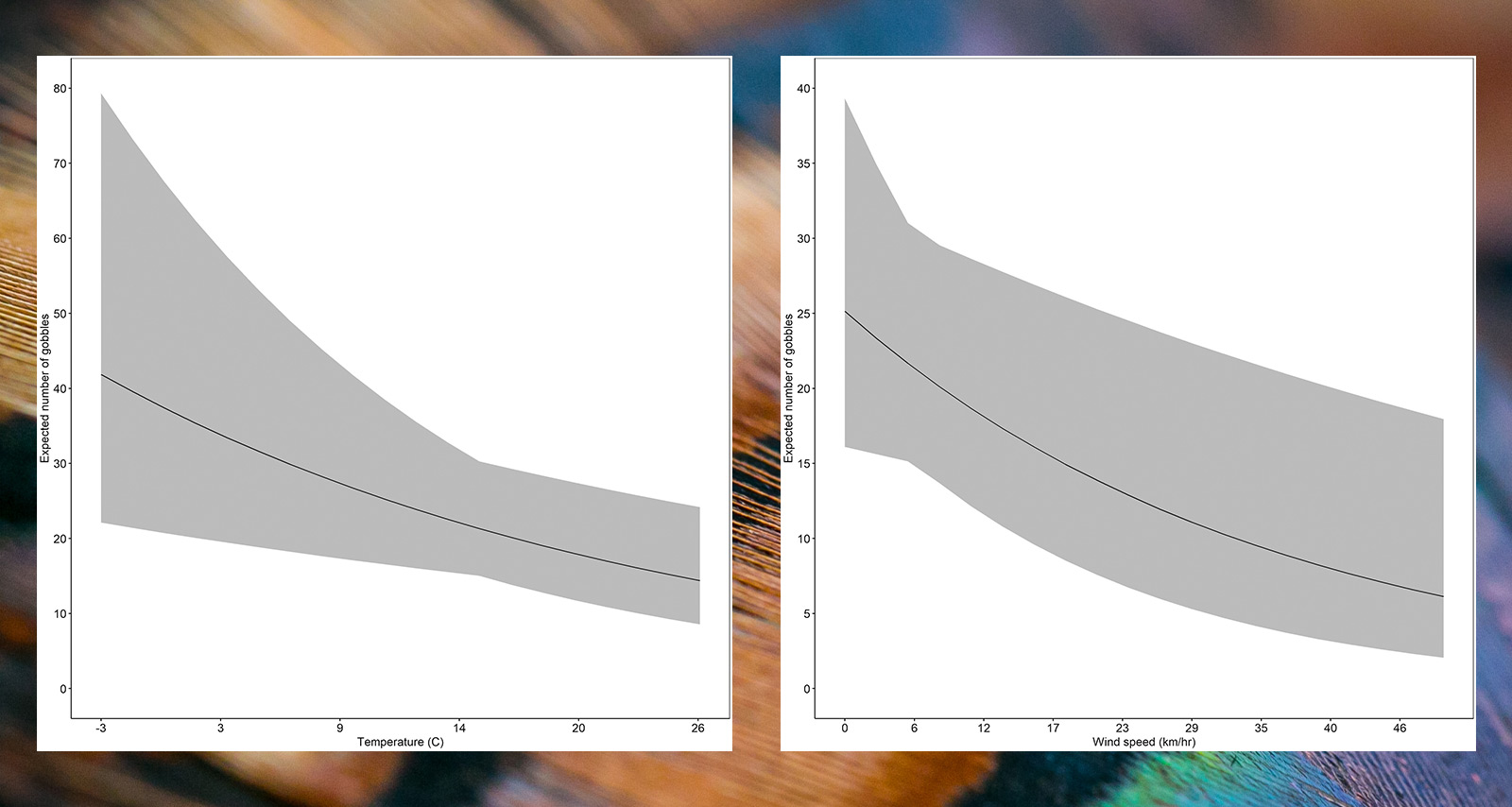

In the fourth study, we found that rain had the biggest negative effect on day-to-day gobbling activity. We also found that increased temperatures negatively impacted gobbling activity, as did wind speeds, especially when over six miles per hour. Humidity did not seem to affect gobbling, while increases in barometric pressures from one day to the next (a common indicator of inclement weather) were related to increased gobbling activity. During rain and high wind, males may be more vulnerable to predation, and gobbles are harder to hear potentially making it less advantageous to call. Given the relationship between increased barometric pressure and passing of storm fronts, turkeys likely increased their gobbling to compensate for lost signaling time during inclement weather. During higher temperatures, one hypothesis would be that males may gobble less in an effort to maintain lower body temperatures to aid thermoregulation.

In the fifth study, we found that metrics associated with hunting activity best predicted areas on the landscape with increased gobbling activity. Specifically, gobbling increased by 40% for every 500 meters further away from public access points turkeys were, while gobbling decreased by 22% for every 500 meters they moved away from private land. After hunting season, gobbles increased by 48% per every 10% increase in female use in an area, increased female use of an area meant more gobbling. Turkeys gobbled less with increased public use but gobbled more when closer to private lands. In conclusion, if someone wanted to increase gobbling activity, they may want to limit access points, implement quotas, or create areas of refuge to reduce hunter activity.

All in all, we found through these studies that males begin to gobble in the spring as daylight increases causing testosterone to rise and while females become receptive to breeding. Gobbling activity peaks during average onset of laying and slowly decreases towards the end of May in a non-hunted population in the Southeast. However, in the presence of hunting, gobbling activity decreases, the amount of gobbling reduction is directly related to the amount of hunting activity, pressure, and removal rate of males. During the reproductive season, some day-to-day variation in gobbling activity is expected and can be partially explained by variation in weather. On hunted sites, gobbling activity varies across the landscape with increased gobbling activity associated with areas of reduced human presence during hunting and increased female presence after hunting.

What’s Next?

In South Carolina, we have continued to run the sound recorders on the non-hunted site and continue to trap and tag birds to understand what turkey ecology looks like on a non-hunted population. Furthermore, we continue to monitor gobbling activity and tag birds in Georgia to investigate potential changes in populations and gobbling activity in relation to season regulations. We have partnered with other Universities, state agencies, and not-for-profit organizations to begin collecting gobbling activity in Alabama and Kentucky to determine site-specific gobbling chronology and investigate potential differences across large geographic regions. We plan to continue expanding the states and areas of research to contribute to this work. One benefit to using sound recorders across many areas and across multiple years is we have a permanent record of gobbling data. In the future, we hope to develop methods to estimate abundance of males across sites and years.

How to Stay Informed

Visit wildturkeylab.com to see our most recent findings and to stay up to date on current work. Also follow Dr. Chamberlain @wildturkeydoc and me @wildturkeynerd on Instagram and Twitter. If you have specific questions or want to reach out to me directly, please message me on the above social or email me at patrick.wightman@uga.edu.