Mule deer are fascinating creatures, and they can certainly be challenging to hunt. To be a successful mule deer hunter, it’s essential to know their physical characteristics, where they call home, and how they compare to other deer you might see in those areas. Knowing a bit about their biology can also tell you a lot about their behavior, which is always useful as a hunter.

Mule deer have been a popular topic for discussion in recent years due to their general population decline. Because of that decline, mule deer hunting opportunities as we know them could change. Being aware of the trends in the mule deer population and what can be done in terms of conservation can help make sure the population stays strong.

Mule Deer Biology & Evolution

Mule deer are thought to be a relatively new species created by hybridization some ten thousand years ago. They are a cross between blacktail deer and whitetail deer, however, mule deer are genetically more closely related to whitetail than blacktail deer.

This is likely due to introgression; the new hybrids often bred back with whitetail deer. This led to the stabilized population of mule deer not being directly 50% blacktail and 50% whitetail. If you attempted to breed a blacktail and whitetail deer today, you would not get a mule deer as a result.

This new hybrid between the blacktail and whitetail deer was better at surviving in the western half of North America than its parent species, so it quickly took hold, and its population grew. This is not usually the case. Hybrid species rarely survive in the wild. There aren’t nearly enough of them to create a new population, and they are often sterile.

Although mule deer are more genetically related to whitetail, they share the most physical similarities with the blacktail deer. In fact, the two species of blacktail deer are now considered to be subspecies of the mule deer.

Mule Deer vs. Whitetail Deer

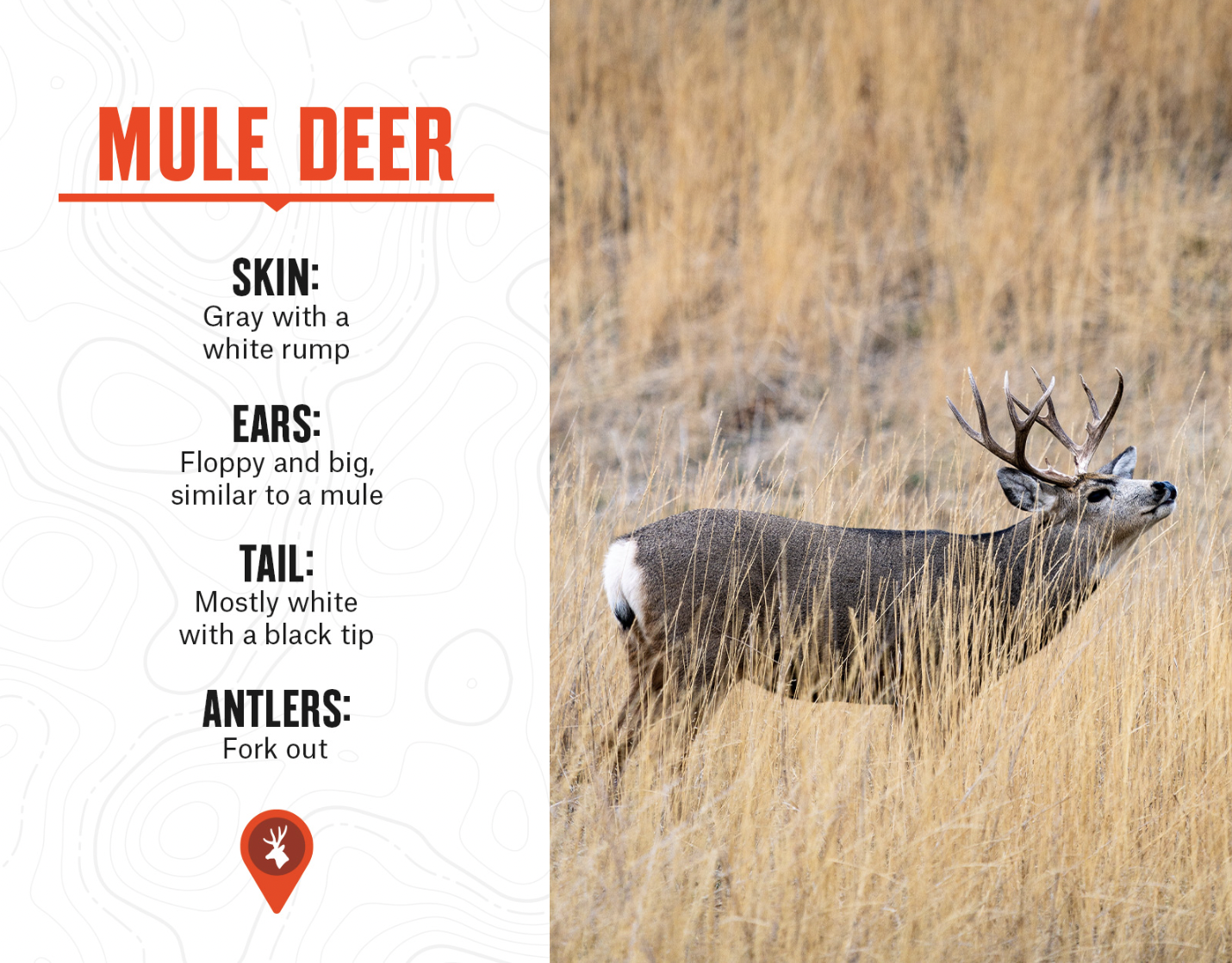

Mule deer have plenty of features that distinguish them from whitetail. Compared to the whitetail deer, mule deer are gray rather than brown, their ears look larger on their head, and their antler tines often fork instead of growing straight. Mule deer have a white rump with a rope-like white and black tail, whereas whitetail deer have a fluffy tail that is brown with a white underside.

A whitetail deer is named for the underside of its tail, which they use as a white flag to signal to other deer there is danger, otherwise, you are going to see a brown rump with a brown tail. This makes the white rump of a mule deer a dead giveaway even at a distance.

Mule deer have noticeably bigger ears than whitetail, but because directly comparing their ears can’t be done unless they are standing together, an easier characteristic to spot is the coloring on the face. A whitetail’s face will be brown with a black nose. There will be white circles around the eyes, and he will be white around the nose, with most of the lower jaw being white. The white from the jaw continues into a white patch on the neck.

A mule deer, on the other hand, will have a face that is mostly white, with the same white patch that goes down to the neck. Some mule deer will have darker colors than others on their face, but they all have an off-white color from their nose to their eyes, and their cheeks will be the same gray color as their body.

The last thing you can look at on the head is a buck’s antlers. Typical whitetail antlers are usually known for growing a main beam and having many tines that grow straight up from the main beam. Mule deer usually grow one or two tines off their main beam excluding their brow tines. Those tines tend to fork instead of grow straight up and, on larger mule deer, those forks will fork.

The Mule Deer’s Range

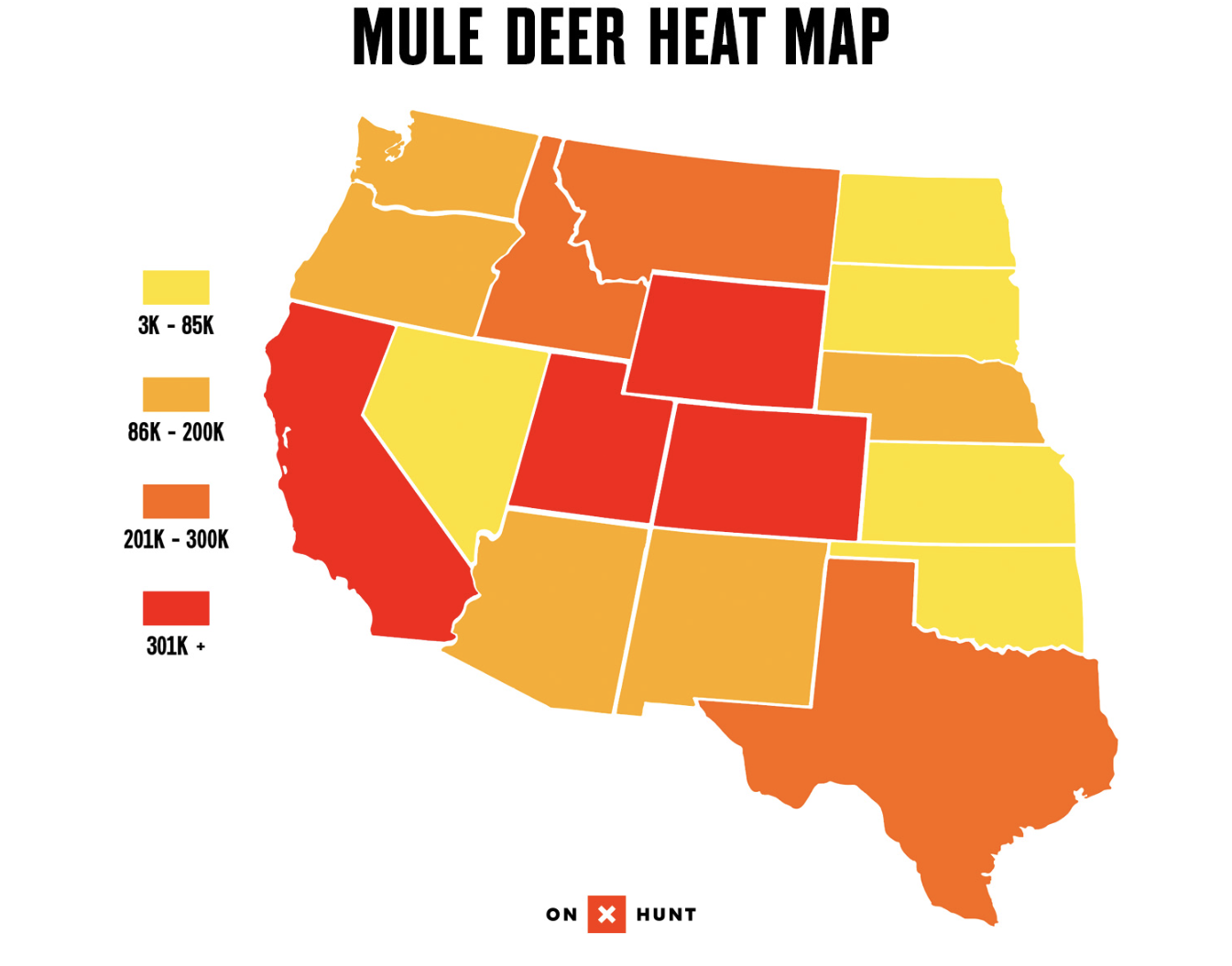

Mule deer populate the western half of North America. They can be found as far north as Alaska and as far south as northern Mexico. Whitetail deer can live their whole life inside a square mile, but mule deer bucks will travel dozens of miles in search of does during the rut, which is often referred to as a migration. Along with moving around for the rut, GPS-collared deer show that mule deer will spend the hotter months of the year in higher and cooler elevations and the colder months in lower and warmer elevations.

California and Colorado have the highest populations of mule deer, with roughly 400,000 each. Wyoming, Montana, and Utah follow close behind in the 300,000 range. Many states across the western United States are seeing declining populations as a result of drought, increased temperatures, habitat loss, and more.

Mule Deer Population Trends

Health

Out of all the deer species in North America, the mule deer is the most at risk. While they have a larger population than blacktail deer, the blacktail thrives in its habitat. The mule deer is losing habitat every day and is constantly out-competed by whitetails. Plus, the official decree is that blacktail deer are a subspecies of mule deer, further complicating things. There are roughly 800,000 blacktails in North America, and there are a little over 3.5 million of the other eight subspecies of mule deer on the continent.

One of the most serious issues mule deer face is chronic wasting disease (CWD). Most people connect CWD to the whitetail population, but it is just as deadly to mule deer. Mule deer have been a catalyst in spreading CWD due to males traveling dozens of miles during the rut and coming into contact with the disease and spreading it to healthy herds. CWD is not running rampant just yet, but it is considered to be the biggest problem mule deer face.

Mule Deer Population Decline

Like the whitetail, mule deer experienced their largest population decline in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This was largely due to overhunting and lack of regulation. In response to this decline, great efforts were put into bringing back all deer species to North America. Whitetail deer responded very well to conservation efforts, and their population exploded as a result. The mule deer population greatly increased in the early 1900s, but they still haven’t recovered to their pre-colonization levels.

In the most recent published report from 2021 regarding blacktail and mule deer population numbers, 6 agencies reported increasing populations, 10 reported stable populations, and 7 reported declining populations. While stable and increasing populations are a positive trend, 7 agencies reporting decreasing populations is not ideal. However, this is fairly different from the 2020 report, which had 12 agencies reporting increasing populations, 6 stable populations, and 4 decreasing populations. You don’t have to go back farther than a year to see that things are not going the right way for mule deer.

Whitetail populations have flourished, in part, due to their ability to adapt to different environments, even those dominated by humans. Suburban homeowners can attest to how whitetail has thrived in their neighborhoods. While whitetail deer can survive without traveling far, the opposite is true for mule deer, for whom large tracts of open land are key to their health. As the West has seen increased development over the past several decades, mule deer populations have suffered. Fencing and roadways further impede their migration. Mule deer may never make it back to their pre-colonization levels because their habitats have declined, and conservation agencies are focusing on that.

Mule Deer Conservation Efforts

Mule deer are fighting an uphill battle. However, there are plenty of things that we can do to help. The fact that so many people want to hunt mule deer is actually good for their population. If you have checked on the price of an out-of-state mule deer tag recently, you will notice that they aren’t exactly cheap, and some of the revenue from hunting licenses goes directly to conservation efforts. Hunting profits pay the salaries of biologists and state employees who are working to improve the outcomes for mule deer.

On the federal level, the United States Forest Service, part of the United States Department of Agriculture, is working to help the mule deer. The majority of their work revolves around securing land for mule deer and keeping it from being developed. They also give generous grants to private agencies that do more boots on the ground work. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is another federal agency that helps with mule deer conservation.

One example of a non-government organization focused solely on mule deer conservation is the Mule Deer Foundation. Along with many other organizations, they work to restore and protect mule deer habitat, lobby for mule deer and mule deer hunting in government policy, promote public education and research around mule deer, and focus on recruiting younger hunters into the hunting world.

All and all, the mule deer is an amazing animal that deserves our help. The majority of their issues stem from human interference or overhunting in the 1800s that they still haven’t recovered from. Mule deer can’t exactly fight for land rights either, and the possibility that CWD wipes out a large amount of the population is all too real if we don’t interfere. We can’t change the fact that mule deer are fighting an uphill battle, but we can certainly get behind them and help push.

Typical vs. Non-Typical Mule Deer

In the family of Cervidae (hoofed ruminant mammals) that live in North America, which include all species of deer and elk, records of legal harvest, and more specifically to be part of Boone and Crockett Club’s data, deer must fall under typical or non-typical status.

Just as it sounds, a typical antler set on a deer or elk would be symmetrical, and antler points would occur in “typical” locations where points are found, technically referred to as points G1, G2, G3, etc. In the West, antlered game are sized according to the number of points on each antler: a 6×6 mule deer would have six points on each antler. In the South and Midwest, a deer would be called a “12-point.” As they say, it’s six of one and a half-dozen of the other. They mean the same thing.

Non-typical antler sets can be freakishly abnormal looking, have an uneven number of points, and those points can be in all shapes, sizes, and directions. The current world record for a non-typical mule deer is known as “The Broder Buck,” taken by Ed Broder in Alberta, Canada, in 1926. This rack had 43 points, 21 points on one antler and 22 on the other, and it scored a 355 2/8.

What should be kept in mind about typical vs. non-typical bucks is that abnormal antler growth indicates some kind of stressor to that animal. It may have been an injury during a fight, low levels of testosterone due to malnutrition or food scarcity, or even disease. In fact, when experts are considering areas with the best quality management indicators present, they are looking at how many typical bucks are present.

FAQ

The term “deer” refers to any animal in the Cervidae family, which has 55 species. Some well-known members of the Cervidae family include whitetail deer, elk, moose, axis deer, and caribou. A mule deer is a specific type of deer falling under the Capreolinae subfamily and the Odocoileus genus.

Physically, mule deer are special because of their large mule-like ears. They also have a large white rump and a sleek gray coat. Mule deer are the newest species of deer native to the North American continent.

On average, an adult mule buck will weigh around 50 to 75 pounds more than an adult whitetail buck. An adult mule doe will weigh around 50 pounds more than an adult whitetail doe.

While there is not a huge difference between whitetail deer and mule deer meat, hunters who know both types of deer well can tell the difference. The two types of meat taste different, but one is not wildly better than the other, and the best tasting meat is left to personal preference.