For Anna Ortega, a PhD Candidate at the University of Wyoming, and her wildlife field technician Zach Andres, the daily office looks an awful lot like a hunter’s dreamscape. The pair’s most recent project, researching the movements of Wyoming’s Sublette mule deer herd, is designed to help us better understand the overall health of the herd and how these animals continue to persist on the landscape.

—

“I think that’s her. Do you hear that?” whispers Anna, crouched behind a veil of tall Great Basin sagebrush.

Zach presses his ear to the receiver. A faint beep echoes from the speaker, barely audible over the humming static and whistling Wyoming wind. It’s mid-November and a cold front is moving in. Anna and Zach are running out of time.

“Yup. That has to be her,” Zach confirms. “Let’s creep over this next ridge and see if we can get eyes on her. I’ll bring the scope. Stay low.”

Anna and Zach grab their packs and stealthily tiptoe towards the ridge, the faint beeping growing louder with every calculated step. They’re getting close. After hours of driving remote roads and miles of postholing though wind-crusted snow, they’re onto her—a female mule deer with a GPS collar. Anna and Zach’s goal: to track the deer using radio telemetry and determine if she has any fawns with her.

For Anna and Zach, spending time with the Sublette mule deer herd is just another day in an exceptional office.

Mule Deer Migration

In Wyoming, mule deer are iconic, beloved, and symbolic; emblematic of vast Western landscapes, open spaces, and wildness. For thousands of years, these animals have captivated humans, provided sustenance, and catalyzed a sense of wonder. From ancient indigenous tribes who hunted and carved petroglyphs depicting mule deer across the state to the modern-day bow hunter who spends weeks chasing a mature buck, there is no denying that Wyoming’s connection to mule deer is both timeless and deeply rooted in its history and culture. Mule deer define Wyoming, and no matter how you look at it, they are among the most valued natural resources in the American West.

Across the globe, animals perform seasonal movements called migrations. For migratory ungulates, moving across the landscape is essential for survival and reproduction. Many hooved animals rely on migration to survive and reproduce in seasonal climates, from caribou in the frigid Arctic to roe deer in Europe. In Wyoming, mule deer move from high-elevation summer ranges that are abundant with nutrient-rich forage to low-elevation winter ranges defined by wide open sagebrush flats and a drier climate. Sadly, migrations are increasingly threatened as humans continue to change the natural world. Roads, fences, energy development, cities, railroads, pipelines: all fragment landscapes and sever the ancient paths of these animals. Climate change, drought, and overgrazing diminish habitat quality, and disease and predation facilitate herd mortalities. Since 1991, mule deer numbers across the state have plummeted by 31% and conservation of this iconic species is just as important now as it was at the turn of the 20th century when market hunting decimated mule deer populations.

The Sublette Mule Deer Herd

For the past five years, Anna’s intellect, drive, and life have been focused on researching the movements of one particular group of mule deer in Wyoming: a portion of the Sublette mule deer herd. Every spring, some members of this herd make a treacherous 150-mile migration from their winter ranges in the Red Desert to their high-elevation summer ranges near Hoback Junction and Jackson Hole. Through oil fields, over fences, and across rivers, these animals follow the spring green up of plants into the high country where they pack on fat, give birth to their fawns and prepare for the upcoming winter. Come fall, these animals, with a new generation of fawns, repeat their journey and return to their winter range to ride out the snow and freezing temps. This particular movement is the world’s longest mule deer migration, and second longest land migration in North America following the 1000-mile journey of caribou in northern Canada.

While this record-breaking migration is undoubtedly impressive, the dynamics of this herd’s movements is still ripe for scientific inquiry. Despite living in the same herd, not all members of this population complete this long-distance migration. One group makes the record breaking 150-mile journey, while some move 70 miles, and others move only 30 miles or less and remain residents on winter range for the entire year. Scientists continue to be vexed by the dynamics of these partial migrations. Why do different migration strategies exist within the same herd? Over the long term, why doesn’t one migration strategy outcompete the others? These questions are at the heart of Anna’s research.

Anna’s Research

Every spring, Anna and her colleagues congregate in the Red Desert among the bitterbrush and rolling sagebrush flats to capture mule deer on their winter range before they begin their spring migration. A helicopter crew armed with two net gunners called “muggers” and an extremely skilled pilot, track, and capture collared female mule deer. They then ferry the animals to Anna and her colleagues at a mobile staging area where they collect a plethora of important data, including blood samples for disease and genetic analysis, fecal samples for understanding diet, weight and body measurements for overall body condition, and an ultrasound to determine if the deer are pregnant (and if they are pregnant, how many fawns they are carrying). Currently, Anna has GPS collars on 72 mule deer does within the Sublette mule deer herd.

After collecting all the necessary data, the animals are then released back into the wild and over the following months, Anna tracks their spring migration, their time on summer range, and their fall migration back to winter range.

Fawn Recruitment Surveys

Come late fall—when most of the deer have completed their fall migration—Anna and Zach conduct fawn recruitment surveys. They spend weeks driving faint two tracks and hiking to the far reaches of the Red Desert to track Anna’s collared does.

The field work isn’t easy. The days are long. The deer are evasive. The GPS collars only provide a location once every 24 hours, making deciphering their current location a tedious task.

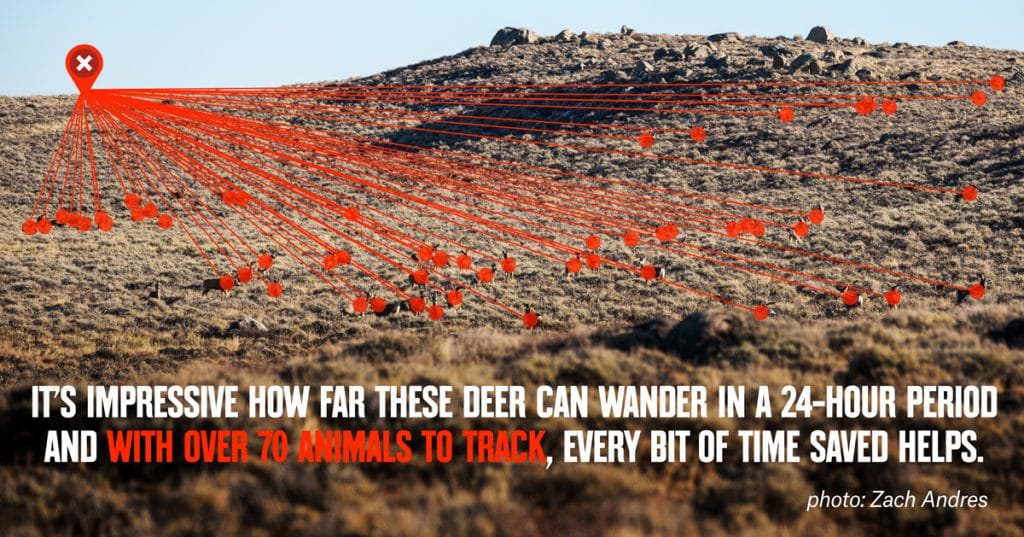

The night before they go into the field, Anna downloads the last known GPS points of the animals into onX. In recent years, Anna has been using onX for her fawn recruitment surveys. The App provides an easier workflow for the scientists and provides them with an easy way to share deer locations and helps them navigate into the field. Before onX, Anna used a traditional GPS unit, but she found it clunky, not user-friendly, and yet another piece of gear to keep track of. Having all the necessary data on a phone provides immense, time-saving value.

onX allows Anna and Zach to make a concise game plan on how to track the animals, provides them with valuable information on roads, offers land ownership information, and the satellite imagery facilitates a successful stalk. Essentially, Anna and Zach rely on onX to get to the animal’s last location, and they then use radio telemetry to get to where the animal currently is located. It’s impressive how far these deer can wander in a 24-hour period and with over 70 animals to track, every bit of time saved helps.

When they find the deer, they determine whether or not the female has any fawns. Armed with the pregnancy data they collected in the spring, Anna and Zach can then determine how many of the fawns actually survived summer and fall migration. This data is incredibly important, allowing scientists to understand how different migratory strategies contribute to the population under varying environmental conditions. For example, different migration tactics may be more successful in severe winters vs. mild winters or dry summers versus wet summers. During different years and under different conditions, the varying migration movements may contribute differently to the overall population of the herd.

In the face of a changing climate, unprecedented long-term drought, and an increasingly fragmented landscape, mule deer need dedicated scientists like Anna to provide wildlife managers with all the necessary tools and understanding to fight this species. The more scientists understand the intricacies of migration, the better conservationists and managers can ensure that populations persist for future generations to enjoy.

If you’re a hunter, wildlife photographer, or simply enjoy seeing wild animals in open country, go thank a biologist. They are working behind the scenes across the globe, dedicated to our wildlife in a way few can truly appreciate.

Guest post written by Ben Kraushaar and Anna Ortega.