Velvet to Hard Bone—Antler Facts and Health

In all of nature, you won’t find a faster-growing true bone than a deer antler. Each year they grow covered in velvet, which mineralizes to hard bone, then is cast off in late winter only to repeat the process. Hunters and wildlife managers use the size and shape of a deer’s antlers to aid in both management and harvest goals. State game laws often refer to antler size in regard to which bucks are legal for harvest. These state regulations are typically based on the recommendations of wildlife biologists charged with managing the state’s deer herd.

You’ve likely heard the terms, “shooter buck,” “12-point,” or “6×6.” In many states, to harvest a buck it needs to have a minimum antler length (often 4” or longer) and/or a certain number of tines.

In this month’s “Whitetail Report,” we take a closer look at what it takes for antlers to change from velvet to bone and how antler health can indicate a buck’s general health.

Velvet to Hard Bone

The current Boone & Crockett world record for a typical whitetail deer is 213 ⅝”, taken in Saskatchewan by Milo N. Hanson. For this buck to grow a set of antlers this large in its six-month growth cycle it would be growing antlers at the rate of almost 1 ¼” per day. That’s over two times faster than the average of up to ½” per day.

No matter how fast antlers grow, it’s an interesting process. Let’s take a look at how antlers grow and change from velvet to hard bone before fall sets in.

By the time antlers get to their hardened state, they are made of 23% calcium, 10% phosphorus, and several other minerals in lesser degrees. Unlike horns, which have an exterior made of keratin (the same as fingernails), do not shed, and grow from the base, antlers grow from the tip.

During the mid-summer growth phase, antlers are covered in velvet, a vascular skin that supplies oxygen and nutrients to the growing bone. As daylight hours grow longer in late spring and summer, deer begin producing less melatonin, and that change initiates the hormone cycles responsible for antler growth.

The process of going from velvet to bone is called mineralization, and it is triggered by testosterone and a reduction of daylight hours. This process begins happening in August, prior to the rut, and it is the point at which antlers stop growing for the year. Blood stops flowing to the velvet, which causes it to die off. This is when you’ll see bucks begin scraping off the deadened skin and revealing the hardened bone underneath. This typically occurs about two weeks before the autumnal equinox and only takes a handful of days to peel off.

Antler Growth, Abnormalities, and Health

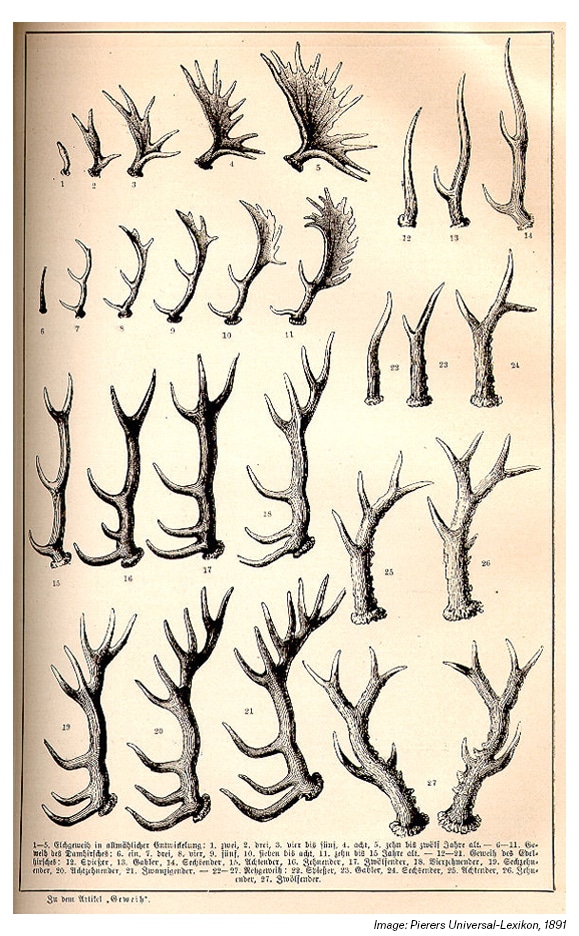

Antlers grow from attachment points on the skull called pedicles. Most bucks don’t start growing antlers until they are at least one year old, though some large fawns born earlier in the year may grow spikes the same year.

Antler growth is slow at first, in the months of April and May, but in June and July they grow rapidly (by as much as two inches a week for older bucks). A buck won’t reach its full genetic potential for antlers until age four, which is when a buck can be called mature. However, maximum antler size, influenced by variable factors like changing food sources, available food, drought, etc., isn’t typically achieved until between the ages of five to seven years old (although by most studies and accounts, bucks rarely live past six in the wild).

You’ve likely heard of “typical” and “non-typical” antlers. It’s such an important distinction with antlers that the Boone & Crockett Club has separate categories for each. To understand the difference, typical antler sets are generally uniform in their shape and the number of tines on each antler (tines are the common “points” that are counted off the main beam of the antler). If you found them both on the ground after shedding, you’d likely be able to see them as a matched set.

Non-typical antlers may have some symmetry between them, but they will also have tines pointed in non-typical directions, or “kickers” (small points protruding from the tines, main beam, or bases) that may twist or point sideways. Specific kickers or tines that grow from the main beam and point downward are called “drop tines.”

See more about typical versus non-typical antlers in this video by the Mississippi State University (MSU) Deer Lab:

Abnormal antler growth that leads to non-typical antlers can have several different causes. Genetic predisposition is one cause. In fact, National Deer Association’s Kip Adams believes that over half of the wild deer population has a genetic predisposition for abnormal antler growth, but most never live long enough to express the abnormality.

While antlers are growing in their velvet stage, they are highly susceptible to injury. Since velvet is much softer than the hardened bone that the antler becomes, any scrapes or tine breaks in this stage will be reflected after the velvet is gone. Remember, antlers grow from the tips (unlike horns), so if a tip is damaged it severely impacts the growth and shape of the antler.

Seeing non-typical antlers doesn’t necessarily mean a buck is unhealthy. Typical or non-typical antlers won’t grow big if there isn’t an abundance of nutritious forage available. Once a buck consumes enough nutrients to maintain its day-to-day energy requirements, the extra calories shift to antler production. So if you’re looking to “grow” bigger antlers on the deer on your land, make sure you have an abundance of nutritious forage and food sources available.