The demand for suppressors in the U.S. hunting industry is being heard loud and clear. According to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), by May 2021 a total of 2.6 million suppressors have been registered to owners in all 42 states in which they are legal to own. Five years earlier that total was 902,805. Ten years ago it was 285,207. It’s estimated that the next ATF report will show the total to be well over three million. What other piece of hunting gear has grown nearly 1,000% in sales in the last decade?

What hunters are embracing are the benefits that suppressors bring to the hunt. Benefits that include hearing protection, recoil reduction, masking the source of the shot, getting back on target quicker for second shots, and a bump in velocity. And now that it’s easier than ever to purchase a suppressor, thanks to companies like Silencer Central, hunters everywhere are experiencing how silence really is golden.

Is It ‘Silencer’ or ‘Suppressor’?

Silencers and suppressors are the same things; although it’s more accurate to say suppressor because they only suppress sound. They don’t make guns silent.

“I have a tendency to call them silencers,” says Silencer Central founder and CEO Brandon Maddox, “because that’s what the ATF calls them. That’s also what the originator patented it as. So my thinking is that if your consumers are calling it one thing you should call it that too. But I’ve seen that once a customer buys one they immediately start calling it a suppressor.”

The term “silencer” has history, however. In all legal documents, from the original patent to its subsequent taxation and updating individual state codes to make them legal, they are referred to as silencers. In movies, they’re called silencers, as well as in many video games. It’s a misnomer, really, but for the last 100-plus years that’s what most people have called them so silencer is familiar to most.

Wait, What About Cans?

Cans mean the same thing. Walk the floor of a gun show and you’ll hear “cans” thrown around as a shorthand reference to suppressors.

“I think it came from a pop can,” says Maddox. “Just having that shape like a can. If you look at some of the older machine guns, some of the suppressors on there are really, really big, almost like a Coke can.”

The History of Suppressors: From Invention to Regulation

In 1902 American inventor and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) graduate Hiram Percy Maxim made the first silencer commercially available to the general public. For Hiram, firearms were already a family affair. His father, Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim, was the inventor of the first portable, fully automatic machine gun: the Maxim Gun.

By 1909 the Maxim Silencer was patented. This tubular device, which could be attached to firearms ranging from .22 to .45 to reduce noise and muzzle flash, was advertised heavily for mail orders in sporting goods catalogs. Even President Theodore Roosevelt had a Maxim Silencer at the end of his Winchester 1894 carbine. It was claimed that he used it for early morning hunts on his property so he wouldn’t wake his neighbors.

In 1934 silencers got heavily taxed. The National Firearms Act (NFA) passed, requiring a $200 tax on most firearms (more than $3,500 by today’s standard) and that the buyer register them with the Secretary of the Treasury. Overnight, suppressors became cost-prohibitive to own or continue manufacturing, essentially silencing their sales for the next four decades.

“One of the things that has been hypothesized from the research I’ve done,” says Maddox, “is that the original NFA process was aimed at machine guns. One theory as to why silencers got thrown into it is that it was during the Depression and they were afraid that people would poach their neighbors’ cattle for food. But another suggestion from my research also said handguns were initially included in the tax but they got swapped at the last minute for silencers so those firearms could be spared from the tax.

“My own hypothesis as to why they were included is that there wasn’t an advocate at the table asking why we’re trying to highly regulate these suppressors. Because they’re not a public safety issue. That’s my guess.”

Firearms subject to the 1934 NFA included shotguns and rifles having barrels less than 18 inches in length and certain firearms described as “any other weapons,” which broadly encompassed machine guns and silencers. The same $200 tax applies to firearm and suppressor purchases today—it never went away.

Why You Should Use a Suppressor for Hunting

“The obvious benefit of a suppressor is its quieter sound protecting your ears and the ears of those around you,” says Maddox. Decibel levels for firearms average between 140 and 165 dB. Most quality suppressors, like the Banish 30, can reduce the decibel output of a rifle shot by over 30 dB.

“Hearing loss, now in this generation, is much more of a safety concern.”

By bringing a gunshot down to the 110-120 dB range it brings the dB down to the same decibel as a rock concert, but one you only hear for three to five milliseconds, which is the average length of a gunshot’s acoustic disturbance.

“Personally speaking,” says Pursue the Wild’s Kristy Titus, “my dad has 90% hearing loss from working in a sawmill, running chainsaws and heavy equipment, and shooting guns. Hearing loss, now in this generation, is much more of a safety concern.”

Titus, in addition to serving as an onX Hunt Ambassador, signed on as a Silencer Central Ambassador in 2022.

“So much of what we do with hunting in the backcountry happens so quickly,” says Titus. “As a hunter, I always have good intentions of shoving foam in my ears but a lot of time in the heat of the moment that step is overlooked. It’s critically important, especially as you become older. But shooting suppressed is going to protect us.”

Hunting with a suppressor goes beyond hearing protection, though that alone is worth owning one. There are several other in-field benefits that can make a hunt more successful and more comfortable for the shooter.

“The real number one reason someone should own a suppressor is the advantage it gives the hunter,” says Maddox. “I started with suppressors by shooting varmints so they couldn’t tell where the shot came from. A lot of hunters might call in three coyotes, shoot one, and the other two are gone, but in a scenario where they’re using a suppressor, the other two are looking around wondering where the shot came from. Then you can get that additional shot.”

Suppressors mask the source of a gunshot in two ways. Visually, the internal baffles of the suppressor capture the expanding gas, slowing and cooling it, which conceals most of the muzzle flash one normally sees firing a gun.

Regarding the sound of the shot, as these baffles modulate the speed and pressure of the propellant gas from the muzzle it dissipates its kinetic energy into a larger surface area. Directing this noise through baffles (just like a car muffler) it transforms its energy into heat. This is why a suppressed gunshot can sound “different,” or muted, making it more difficult to source. Snipers in the military are trained to shoot, when possible, so the bullet passes by large objects that reflect the “crack” sound of a supersonic bullet, making it nearly impossible to track the sound to its origination point. The shot sounds like it came from everywhere at once.

“I find most people also don’t realize the benefit of recoil reduction until the first time they shoot suppressed,” says Maddox. “A lot of these bigger caliber guns may come with a break, but when you put a suppressor on too you get the benefit of the break and the recoil reduction from the suppressor. This would even allow you to go up on your caliber and not have as much recoil one would normally have.”

“Being a smaller shooter,” says Titus, “the recoil reduction you get is very beneficial. And it helps balance your rifle so you’re using less of your body to drive and influence the shot onto a target. The other thing is you get a little bump in velocity. If anything, it might make your shots flatter and you’ll want to re-zero after getting a new suppressor.”

Myths About Suppressors

“In my opinion, there’s no disadvantage of running a can,” says Titus. “A lot of people think that if you put a can on you’re going to lose accuracy and that’s simply not true.”

“You see younger guys come to our booth at shows and they say, ‘It’s going to hurt my velocity,’” says Maddox, “and in the video games it does, but in reality it doesn’t. In fact, a suppressor speeds it up.”

It’s hard to fault those who grew up gaming for this falsehood. Of the 783 documented first-person shooter games, the suppressor finds its way in many of the most popular ones. From the Doom franchise that launched in 1993 to the current Call of Duty: Warzone, players have looked for advantages in weaponry to go further and last longer in battle. The suppressor was the accessory that would hide your location when you shot, but it came at a cost–slower, shorter, less predictable, and less damaging shots.

The thing about video games is their playability, and playability comes from having a balance. In the real world, the suppressor’s advantage is evident–quieter shots, less recoil, quicker follow-up shots, better-balanced firearms, etc. In the gaming world, programmers don’t want players to have unbalanced advantages where they can dominate every battle. There must have been, therefore, flawed logic that programmers embraced where adding something long and heavy to your weapon would slow down the bullet, make your shots on target less accurate, or reduce the damage from each shot. Those seemed to be the fair trade-offs for not giving up your position when you fired. The generation(s) who spent more time shooting digital guns than real ones held on to that false truth because no one taught them differently.

Another common misconception about suppressors is that they’re illegal. “I’ll still get guys coming up to my booth at gun shows and arguing with me that suppressors aren’t legal,” says Maddox.

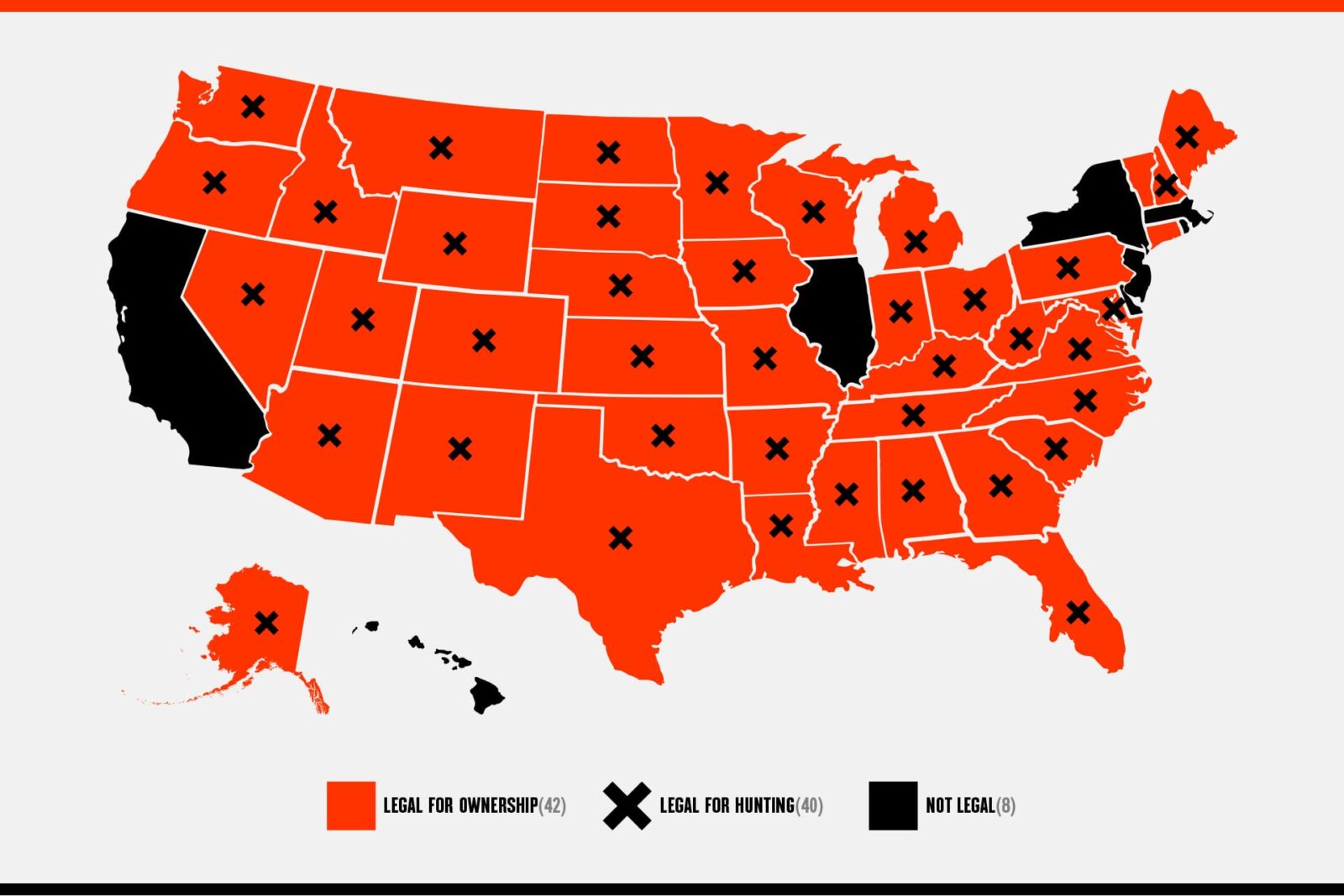

Eight states and the District of Columbia do not allow private ownership of suppressors. Those states are California, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Delaware. The two states where they are legal to own but cannot be used for hunting are Connecticut and Vermont.

How To Buy a Suppressor

Buying a suppressor is now almost as simple as it was to mail order them before 1934. The process allows those 21 and older to buy the $200 federal tax stamp, set up an NFA trust, submit an e-file to the ATF with the necessary paperwork, and wait about 90 days.

While the tasks are simple, there are a lot of steps that need to be taken in the right order. That’s why Silencer Central is set up to handle the entire process of suppressor sales direct to consumers in all 42 states where they are legal. From helping you set up your required ATF account for submitting an e-file and setting up a legal trust, to sending you a complete fingerprint kit, they have dialed in the process. Silencer Cental will even allow you to make payments on your suppressor while you’re waiting for ATF’s approval of your application.

“They make the process so easy,” says Titus. “What Silencer Central does is if you’re at a consumer show they’re at, which they’re at a lot of them, they’ll do your fingerprints electronically. Even if you’re not at a show they’ll handle all your paperwork for you. They’ll set up your trust so you can manage all the legal aspects of owning your suppressor, and they’ll deliver it to your door if you live in one of the 42 states. They just make it really easy.”